Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: October 16, 2025

Lead authors: Rona M. Vail, MD, AAHIVS; Aviva Cantor, DMSc, PA, AAHIVS

Writing group: Sanjiv S. Shah, MD, MPH, AAHIVS; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA, AAHIVS; Samuel T. Merrick, MD, FIDSA; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD, FACP, AAHIVS; Anne K. Monroe, MD, MSPH; Jessica Rodrigues, MPH, MS; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH, MSc, FACP; Brianna L. Norton, DO, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: October 10, 2019

HIV prevention with pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is the use of antiretroviral medications by individuals who do not have HIV to reduce their risk of acquiring HIV. PrEP is a cornerstone of HIV prevention and is strongly endorsed by New York State. However, it is underutilized, particularly by communities disproportionately affected by HIV.

The New York State Ending the Epidemic (ETE) initiative presents strategies to decrease HIV prevalence and end the AIDS epidemic in New York State. The third pillar of the 3-pillar ETE plan is facilitating access to PrEP as a proven strategy to prevent HIV acquisition among individuals at risk. Its inclusion as a pillar of this initiative emphasizes the safety and effectiveness of PrEP as an HIV prevention method. This guideline was developed by the Medical Care Criteria Committee of the NYSDOH AI Clinical Guidelines Program to help clinicians successfully start and continue PrEP for individuals at risk of acquiring HIV.

In support of the ETE initiative and to reduce new HIV infections in New York State, the goals of this guideline are to:

- Increase clinician awareness and knowledge of PrEP efficacy.

- Assist clinicians in identifying candidates for PrEP and increasing PrEP awareness, access, and uptake among individuals at risk of acquiring HIV through sexual and drug use exposures.

- Discuss barriers to PrEP access and encourage clinicians to assist PrEP candidates in reducing or eliminating these barriers.

- Provide clinicians with the information needed to help a PrEP candidate make the best choice regarding oral versus injectable PrEP and daily versus on-demand PrEP.

- Provide evidence-based recommendations for PrEP initiation, management, monitoring, and discontinuation.

Note on “experienced” HIV care providers: The NYSDOH AI Clinical Guidelines Program defines an “experienced HIV care provider” as a practitioner who has been accorded HIV Specialist status by the American Academy of HIV Medicine. Nurse practitioners (NPs) and licensed midwives who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV in collaboration with a physician may be considered experienced HIV care providers if all other practice agreements are met; NPs with more than 3,600 hours of qualifying experience do not require collaboration with a physician (8 NYCRR 79-5:1; 10 NYCRR 85.36; 8 NYCRR 139-6900). Physician assistants who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV under the supervision of an HIV Specialist physician may also be considered experienced HIV care providers (10 NYCRR 94.2).

Improving PrEP Equity, Uptake, and Persistence Through Structural Support and Patient-Centered Choice

PrEP uptake: Although new HIV infections and diagnoses have steadily declined in New York State, these decreases have not been uniform across all groups. Men who have sex with men (MSM), particularly young MSM, and people of color continue to be overrepresented among those newly infected and diagnosed with HIV NYSDOH 2023. Computer simulation modeling suggests that increased PrEP uptake will be the single largest contributor to further reductions in new HIV infections and key to ending the HIV epidemic in New York State Martin, et al. 2020. However, data indicate that people of color, cisgender women, and individuals accessing Medicaid, 3 groups overrepresented among people with HIV, are accessing PrEP at lower levels than other groups in whom the disease burden is high Ending the Epidemic Dashboard 2025. For example, in 2023, 20.9% of new HIV diagnoses in New York State were in cisgender women and people assigned female at birth NYSDOH 2023 but just 8% of all individuals who accessed PrEP in New York State were women Ending the Epidemic Dashboard 2025. When broken down by race, 43% of PrEP prescriptions were written for White individuals, 12% for Black individuals, 10% for Hispanic individuals, 27% for “unknown,” 4% for Asian/Pacific Islander individuals, and 4% for “other” individuals Ending the Epidemic Dashboard 2025.

Barriers to PrEP access, use, and persistence: PrEP uptake, adherence, and persistence vary widely across populations and are influenced by structural, care provider, and individual-level factors. Suboptimal awareness and acceptance of PrEP among at-risk individuals and their care providers remain key barriers to initiation Townes, et al. 2021; Bazzi, et al. 2018; Mayer, et al. 2018.

Among Black MSM, low perceived HIV risk, stigma, and medical mistrust rooted in systemic racism significantly impede PrEP use. Those unaware of PrEP often have lower HIV testing rates, limited HIV knowledge, and higher rates of transactional sex Russ, et al. 2021. Additional structural barriers include lack of insurance and limited access to culturally competent care. Women who engage in sex work and use drugs face unique challenges including competing survival needs, low risk perception, and difficulty with daily adherence. Effective strategies include nonjudgmental care provider communication, integrated HIV and substance use care, and adherence support. Clinicians may struggle with limited infrastructure and discomfort discussing sex work Harris, et al. 2024. Young MSM of color face care provider bias and a lack of culturally concordant care. Hiring staff with shared identities, providing affirming services, and LGBTQ+ cultural competency training can improve PrEP engagement Ribas Rietti Souto, et al. 2024. Individuals who inject drugs have low to moderate levels of PrEP awareness and very low PrEP uptake, varying from 0% to 3% in a systematic review Mistler, et al. 2021. There has been little research into effective ways to increase PrEP uptake in people who inject drugs. Addressing structural and stigma-related barriers for this population is essential. One study found that conversations about HIV prevention at syringe-exchange programs significantly increased PrEP awareness Walters, et al. 2020.

Despite increased availability of oral PrEP (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine [TDF/FTC] or tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (TAF/FTCJoseph Davey, et al. 2025. Expanding the number of PrEP prescribers beyond HIV and sexual health specialists to include primary care providers is essential. Additionally, clinicians must address unconscious bias, avoid assumptions about sexual or drug use behavior, and gain comfort with taking sexual histories Calabrese, et al. 2018; Edelman, et al. 2017; Calabrese, et al. 2014. If a patient requests PrEP and it is not medically contraindicated, it should be prescribed with appropriate follow-up.

Successful PrEP programs will address stigma, mistrust, low HIV risk perception, and structural inequities through culturally responsive, patient-centered care and offer flexible PrEP options, including the ability to switch modalities.

PrEP persistence and episodic use: PrEP effectiveness depends on sustained use, yet discontinuation remains common. A meta-analysis of oral PrEP use found that 41% of users discontinued within 6 months and 35.6% between 7 and 12 months, with discontinuation strongly associated with increased HIV incidence (2.1–3.6 vs. 0.0–0.1 per 100 person-years) Guo, et al. 2024. Discontinuation is more likely among younger people, individuals using substances (especially methamphetamine), women, and those with lower education or high out-of-pocket costs. Medicaid coverage, affordability, and living in an Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE) county are associated with improved persistence Dawit, et al. 2024. Public transportation reliance is associated with lower continuation Sharpe, et al. 2023, while use of health-system specialty pharmacies (HSSPs) improves persistence at 6, 12, and 18 months Whelchel, et al. 2023.

Frequent required visits and laboratory testing can be experienced as “overmedicalization” and deter continuation. Although quarterly laboratory monitoring is standard for oral PrEP, it is not evidence-based and should be adapted to patient needs. At-home HIV testing or conveniently located external laboratory centers with annual in-person visits and telemedicine options can reduce structural barriers Siegler, et al. 2019.

PrEP use may be noncontinuous, with individuals cycling on and off based on perceived HIV risk. Discontinuation does not always reflect program failure Reed, et al. 2021. For individuals who wish to stay on PrEP, removing barriers and tailoring care are essential.

PrEP choice: Offering individuals a choice of HIV prevention modalities including oral PrEP, long-acting injectable PrEP, and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) improves uptake, adherence, persistence, and satisfaction. In the SEARCH trial, a dynamic choice model allowing participants to switch modalities led to more than 5-fold higher biomedical coverage (69.7% vs. 13.3%) and reduced HIV incidence (0% vs. 1.8%) compared with standard of care Kamya, et al. 2024. A modeling analysis projected that structured choice, including the option of CAB LA, could reduce HIV incidence by one-third over 10 years and be cost-effective across eastern and southern Africa Phillips, et al. 2025. In the ImPrEP CAB Brasil study, 83% of participants opted for CAB LA over oral PrEP after receiving options counseling, citing challenges with daily pills and confidence in injectables Grinsztejn, et al. 2025. PrEP options counseling significantly increased CAB LA uptake and satisfaction, highlighting the importance of decision-support tools in personalized HIV prevention. The approval of SC LEN adds another important PrEP choice and may further increase uptake and persistence.

Gender-affirming care and PrEP: Transgender women experience a disproportionate burden of HIV, and PrEP uptake is likely to have a high impact in transgender women who are sexually active and for whom PrEP is indicated Malone, et al. 2021. Transgender women have low rates of PrEP uptake and high rates of discontinuation Scott, et al. 2019, and gender-affirming care and access to hormone therapy can increase PrEP uptake and adherence Sevelius, et al. 2016. Gender-affirming care has been shown to improve health outcomes for transgender people, and providing gender-affirming hormone therapy in the context of primary care was associated with reduced rates of HIV seropositivity in the LEGACY study Reisner, et al. 2025. Concerns about interactions between PrEP medications and estrogen may lead to avoidance or missed doses, although studies show that TDF/FTC, TAF/FTC, CAB LA, and SC LEN do not significantly affect hormone levels Kelley, et al. 2025; Blumenthal, et al. 2022; Grant, et al. 2021; Blair, et al. 2020; Hiransuthikul, et al. 2019. Providing reassurance about this lack of interaction can also increase uptake.

Comprehensive services and support: To enhance PrEP success, it is essential that clinicians collaborate with others inside and outside their organizations to address individuals’ social determinants of health and offer services such as:

- Mental health and substance use treatment

- Case management and navigation

- Housing assistance and benefits counseling

- Support groups and peer networks

| KEY POINTS |

|

PrEP Coverage

Coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA): In 2023, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force published an updated grade A recommendation that clinicians should “prescribe preexposure prophylaxis using effective antiretroviral therapy to persons at increased risk of HIV acquisition to decrease the risk of acquiring HIV” USPSTF 2023. This federal recommendation recognizes PrEP as a preventive service to be covered under the ACA, a significant step toward increasing access to PrEP, and further affirms PrEP as a highly effective HIV prevention strategy clinicians can and should provide to their patients. Of note, ACA plans and Medicare Part B and D not only cover PrEP medications but also testing and monitoring without cost-sharing CMS 2024.

Coverage in New York State: New York State Senate Bill S825 (2023-2024 Legislative Session) mandates that certain large group policies cover HIV PrEP and PEP. New York State Medicaid and the Essential Plan cover PrEP medications, visits, monitoring, and testing without cost-sharing (see NYS Medicaid Coverage for HIV PrEP Related Services).

| RESOURCES |

|

FDA-Approved PrEP Agents

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate 300 mg/emtricitabine 200 mg in a fixed-dose tablet (TDF/FTC; Truvada): TDF/FTC is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use as PrEP as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention strategy for all individuals at risk of acquiring HIV. Multiple randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy of TDF/FTC as PrEP for preventing HIV infection in all risk populations when taken daily as directed McCormack, et al. 2016; Choopanya, et al. 2013; Baeten, et al. 2012; Grant, et al. 2010. Based on 2 large clinical trials, TDF/FTC can also be taken before and after sex (on-demand dosing) for appropriate candidates (see guideline section Choosing and Prescribing a PrEP Regimen > Alternative Oral Dosing: On-Demand PrEP), although this dosing strategy is not FDA-approved.

Tenofovir alafenamide 25 mg/emtricitabine 200 mg in a fixed-dose tablet (TAF/FTC; Descovy): TAF/FTC was noninferior to TDF/FTC in a study of men who have sex with men (MSM) and a small number of transgender women who have sex with men Mayer, et al. 2020. Daily TAF/FTC was approved by the FDA in October 2019 for HIV prevention through sexual exposure in those groups FDA(b) 2025. On-demand dosing of TAF/FTC has not been studied.

In the PURPOSE 1 trial, rates of HIV seroconversion with TAF/FTC were not different from the background rates of HIV seroconversion in cisgender adolescent and adult women overall Bekker, et al. 2024. However, in a subanalysis of the study TAF/FTC was effective when taken with medium to high adherence and reduced HIV incidence by 89% with 2 or more doses per week Kiweewa, et al. 2025. Although TAF/FTC is not FDA-approved for receptive vaginal sex, given the data noted above it is reasonable as part of shared decision-making to offer TAF/FTC as an alternative PrEP option for HIV exposures through receptive vaginal sex for individuals in whom TDF/FTC is not tolerated or not desired.

Long-acting injectable cabotegravir (CAB LA; Apretude): CAB LA is an integrase strand transfer inhibitor given as an intramuscular injection every 2 months after an optional 4-week lead-in of oral CAB (Vocabria) and 2 initial injections given 4 weeks apart. CAB LA was statistically superior to oral TDF/FTC as PrEP (due to imperfect adherence to oral PrEP) in MSM, transgender women, and cisgender women Delany-Moretlwe, et al. 2022; Landovitz, et al. 2021. CAB LA was approved by the FDA in December 2021 for prevention of HIV via all sexual exposures FDA 2021.

Subcutaneous lenacapavir (SC LEN; Yeztugo): SC LEN is a capsid inhibitor dosed subcutaneously every 6 months along with an initial oral loading dose of two 300 mg tablets on the day of the initial injections and again on the next day after the injections. In the PURPOSE 1 trial in cisgender adolescent and adult women Bekker, et al. 2024 and PURPOSE 2 trial in men and gender-diverse populations who have sex with men Kelley, et al. 2025, SC LEN was statistically superior to TDF/FTC (PURPOSE 1 and 2) and to TAF/FTC (PURPOSE 1) in preventing HIV infection for all sexual exposures (due to imperfect adherence to oral PrEP). The PURPOSE 3 (cisgender women in the United States), PURPOSE 4 (people who inject drugs), and PURPOSE 5 (individuals at high risk of HIV in France and the United Kingdom) trials are ongoing. SC LEN was approved by the FDA in June 2025 for prevention of HIV via all sexual exposures FDA(d) 2025.

Who Should Use PrEP

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

PrEP Candidates

Contraindications to PrEP

|

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CrCl, creatinine clearance; nPEP, non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; TAF/FTC, tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy); TDF/FTC; tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada). |

PrEP Candidates

PrEP is part of a comprehensive HIV prevention plan and should be offered to individuals, including adolescents who meet the prescribing criteria, and who are assessed as or who self-identify as being at increased risk of acquiring HIV through sexual or injection drug exposure.

| NEW YORK STATE LAW |

|

Box 1, below, shows candidates who should be offered PrEP and factors that do not disqualify candidates from PrEP. See Appendix B: Studies That Support the Use of PrEP in Different Populations for a discussion of the studies that support the use of PrEP in different populations.

| Box 1: Candidates for Pre-exposure Prophylaxis |

Offer pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to individuals who are candidates, including those who:

Do not withhold PrEP from eligible candidates who:

|

Contraindications to PrEP

Exposure to HIV in the previous 72 hours: Individuals with potential HIV exposure in the previous 72 hours should be prescribed PEP and provided a 4-week follow-up to transition to PrEP. See the NYSDOH AI guideline PEP to Prevent HIV Infection.

HIV infection: The 2-drug PrEP regimens of TDF/FTC and TAF/FTC and the single-drug regimens of long-acting injectable cabotegravir (CAB LA) and subcutaneous lenacapavir (SC LEN) are inadequate for treating established HIV infection; therefore, PrEP should not be initiated unless an individual is tested for HIV at initiation or within 1 week before the proposed initiation. If HIV infection is confirmed, PrEP should immediately be converted to a fully suppressive HIV treatment regimen. See guideline section Managing a Positive HIV Test Result.

Renal dysfunction: TDF is contraindicated for individuals with a CrCl <60 mL/min at the time of PrEP initiation and should be discontinued if CrCl drops to <50 mL/min FDA 2024. TAF/FTC can be prescribed in individuals with a CrCl ≥30 mL/min. Serum creatinine levels can vary and be affected by factors other than renal disease; therefore, before a decision is made to forgo or discontinue oral PrEP, decreased CrCl should be verified through repeat testing, and other causes of spurious creatinine elevation (e.g., use of creatine-containing protein supplements) or reversible causes (e.g., use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) should be ruled out. CAB LA and SC LEN are safe to use in individuals with renal dysfunction.

Fillers, implants, and silicone in the buttocks and hips: Caution should be exercised when considering CAB LA as PrEP in individuals with silicone and implants in buttocks and hips, as absorption of CAB LA may be compromised.

Drug-drug interactions: CAB LA as PrEP is contraindicated with some antiseizure medications and rifamycins. There are several important drug-drug interactions for SC LEN that require dose adjustment and consideration of alternative PrEP options. Check for drug-drug interactions before prescribing PrEP. See NYSDOH AI Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From HIV Prevention to Treatment and University of Liverpool HIV Drug Interactions.

Other HIV prevention methods: Discuss other HIV prevention methods, such as condom use and safer sex practices, in the context of PrEP, particularly for individuals with contraindications or intolerance to current PrEP options.

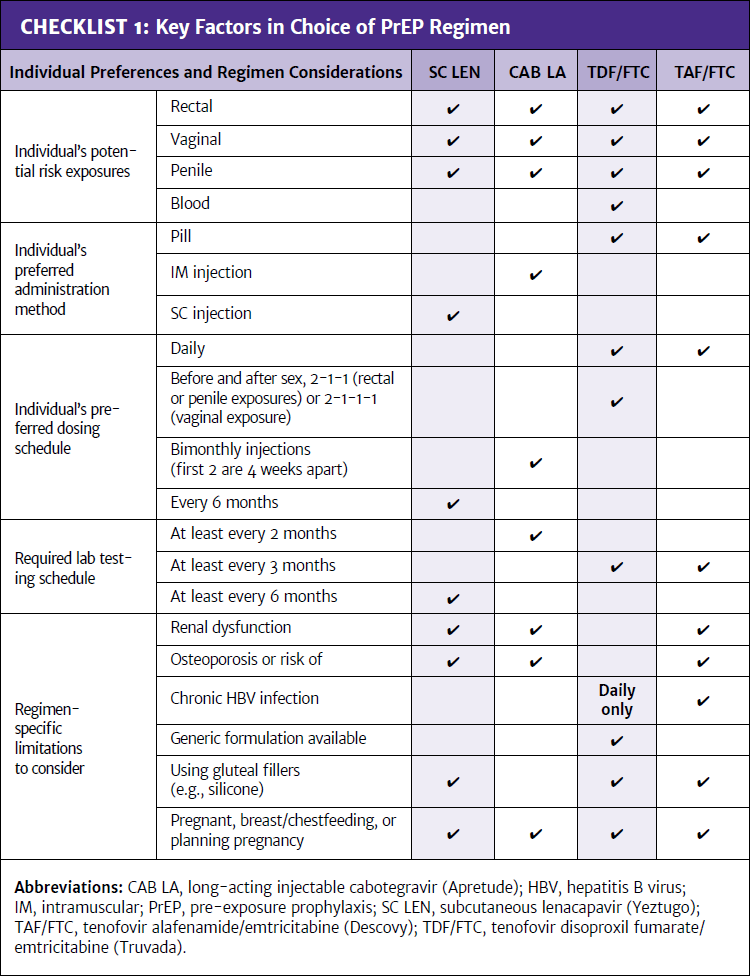

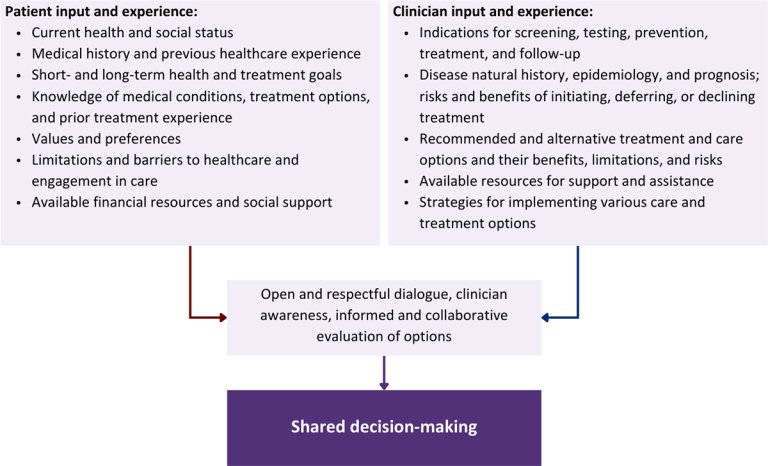

Comparing PrEP Regimens

All current pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) options are highly effective when taken as directed. Shared decision-making allows patient preferences and clinical considerations to guide the choice of the best PrEP option for each candidate (see Table 1 and Table 2, below).

| Abbreviations: 3TC, lamivudine; ART, antiretroviral therapy; CrCl, creatinine clearance; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HBV, hepatitis B virus; IM, intramuscular; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MSM, men who have sex with men; NYCRR, New York Codes, Rules and Regulations; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; TasP, treatment-as-prevention.

Notes:

|

||||

| Table 1: Key Clinical and Logistical Factors in Choosing a PrEP Regimen (details provided in discussion that follows; also see Checklist 1: Key Factors in Choice of PrEP Regimen) |

||||

| TDF/FTC (tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine; Truvada) |

TAF/FTC (tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine; Descovy) |

CAB LA (long-acting injectable cabotegravir; Apretude) |

SC LEN (long-acting injectable lenacapavir; Yeztugo) |

Comments |

| Indications | ||||

| Sexual and injection drug exposures use in adults and adolescents weighing ≥35 kg |

|

|

|

|

| Time to Protection [a] | ||||

|

Not defined, but expected to be ≤7 days | Estimated efficacy at 7 days | 2 hours after second oral loading dose | See guideline section Comparing PrEP Regimens > Time to Protection |

| Renal Safety | ||||

|

|

Increased monitoring for adverse effects is recommended if CrCl <30 mL/min. | Increased monitoring for adverse effects is recommended if CrCl <15 mL/min. | More frequent monitoring may be required for individuals at increased risk of renal disease (i.e., hypertension, diabetes, age >40 years). |

| Bone Safety | ||||

| Potential decrease in bone mineral density; meta-analysis shows good safety Pilkington, et al. 2018 |

|

Preferred option for prevention of sexual exposures in all individuals with osteopenia or osteoporosis | Preferred option for prevention of sexual exposures in all individuals with osteopenia or osteoporosis | — |

| Weight and LDL Cholesterol | ||||

|

|

|

No information on weight or cholesterol reported | — |

| Dosing | ||||

|

Daily dosing only |

|

|

— |

| Same-Day Initiation | ||||

| Generic TDF/FTC is a preferred insurance option and is usually available for same-day initiation. | May require prior insurance authorization |

|

|

— |

| Common Adverse Effects | ||||

| Diarrhea (6%), nausea (5%) Glidden, et al. 2016 | Diarrhea (5%), nausea (4%) Mayer, et al. 2020 | Injection site reactions (32% to 81%) Delany-Moretlwe, et al. 2022; Landovitz, et al. 2021, which are mostly mild and greatest initially | Injection site reactions including potential pain, nodules, and erythema (69% to 83%) Kelley, et al. 2025; Bekker, et al. 2024, mostly grades 1 and 2, affected by injection technique | — |

| Use During or When Planning Pregnancy | ||||

| May be continued through pregnancy and breast/chestfeeding | May be continued through pregnancy and breast/chestfeeding |

|

|

|

| Use With Oral Contraceptives | ||||

| No interaction expected based on pharmacokinetic data | No interaction expected based on pharmacokinetic data | No interaction expected based on pharmacokinetic data | May increase concentrations of oral contraceptives but no dose adjustment needed | No dose adjustment of emergency contraception needed for all PrEP regimens |

| Use With Gender-Affirming Hormones | ||||

| No significant interaction with estrogen or testosterone | No significant interaction with estrogen or testosterone | No significant interaction with estrogen or testosterone |

|

— |

| Patients With Active Chronic HBV [b,c] | ||||

|

Active against and FDA-approved for treatment of HBV infection | Not active against HBV infection | Not active against HBV infection | Monitor closely for rebound HBV viremia if TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC is discontinued in a patient with chronic HBV |

| Drug-Drug Interactions | ||||

| See NYSDOH AI Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From HIV Prevention to Treatment > TDF and TAF Interactions | See NYSDOH AI Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From Prevention to Treatment > TDF and TAF Interactions | See NYSDOH AI Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From Prevention to Treatment > CAB Interactions | See NYSDOH AI Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From Prevention to Treatment > LEN Interactions | Drug-drug interactions for SC LEN may require additional dosing or an alternative PrEP regimen. |

| Generic Formulation Availability | ||||

| Generic TDF/FTC is available | Brand only | Brand only | Brand only | TAF/FTC, CAB LA, and SC LEN may require prior insurance authorization. |

Download Table 1: Key Clinical and Logistical Factors in Choosing a PrEP Regimen Printable PDF

| Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CAB LA, long-acting injectable cabotegravir (Apretude); HBV, hepatitis B virus; HSV, herpes simplex virus; SC LEN, subcutaneous lenacapavir (Yeztugo) PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection; TAF/FTC, tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy); TDF/FTC, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada). | |||

| Table 2: Benefits, Limitations, and Risks of Available PrEP Regimens | |||

| All PrEP Regimens | Oral PrEP With TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC | Injectable PrEP With CAB LA | Injectable PrEP With SC LEN |

| Benefits | |||

|

|

|

|

| Limitations | |||

|

|

|

|

| Risks | |||

| Continued use after undiagnosed HIV infection may result in development of drug-resistant virus |

|

|

|

Download Table 2: Benefits, Limitations, and Risks of Available PrEP Regimens Printable PDF

HBV Infection

Daily tenofovir-containing PrEP is preferred for individuals with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV). Unlike tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) and tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (TAF/FTC), long-acting injectable cabotegravir (CAB LA) and subcutaneous lenacapavir (SC LEN) do not prevent or treat HBV infection. When considering or switching to a long-acting injectable PrEP regimen, perform HBV testing if an individual’s hepatitis serologies are unknown or if there was borderline or low-level immunity in the past. Unrecognized chronic HBV can flare when tenofovir-containing regimens are discontinued. Individuals with chronic HBV who are switching from an oral PrEP regimen will need to continue oral tenofovir or other HBV treatment options while using CAB LA or SC LEN. Non–HBV-immune individuals should be offered routine vaccination to prevent HBV infection. See the NYSDOH AI guideline Prevention and Management of Hepatitis B Virus Infection in Adults With HIV.

Time to Protection

The time to protection against HIV infection after PrEP initiation is not definitively established. Whether the key to protection is drug levels in genital and rectal tissue, plasma blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), or more likely, a combination of tissue and PBMC levels is under debate. Most of what is known is from animal studies, human tissue studies, and pharmacokinetic modeling. There are no studies with clinical endpoints. In animal models and observational studies, post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) has been effective if initiated within 72 hours after exposure, which raises questions about the specific drug concentrations in tissue required to protect against HIV infection.

TDF/FTC: Early pharmacokinetic modeling data demonstrated that 7 days of daily TDF/FTC for PrEP are required to achieve maximal protective concentrations in rectal tissue, and 20 days of daily dosing are required to achieve maximal protective concentrations in cervicovaginal tissue Louissaint, et al. 2013; Anderson, et al. 2012; Patterson, et al. 2011. Newer pharmacokinetic modeling data suggest that TDF/FTC is likely protective within 1 week of dosing in both rectal and genital compartments and PBMCs Hendrix, et al. 2016; Seifert, et al. 2016. Emtricitabine triphosphate (active metabolite of emtricitabine) reaches steady-state and therapeutic concentrations very quickly in vaginal tissue, and tenofovir diphosphate (active metabolite of tenofovir) reaches concentrations more slowly, potentially affording vaginal protection quite early from emtricitabine triphosphate while tenofovir diphosphate concentrations accumulate Cottrell, et al. 2016; Seifert, et al. 2016.

Studies have shown that initiating PrEP with a double dose (2 tablets) of TDF/FTC confers protective levels after 2 hours both rectally and vaginally Chawki, et al. 2024; Cottrell, et al. 2016. Therefore, a double dose of TDF/FTC at initiation, when more immediate protection is desired, is recommended, otherwise daily dosing for 7 days will achieve optimal protective levels of medication in PBMCs and genital and rectal tissue, acknowledging that protection is likely conferred earlier.

TAF/FTC: Time to protection for TAF/FTC is also unclear. TAF had a faster time to 90% effective concentrations (EC90) than TDF (4 hours vs. 3 days) and significantly higher steady-state concentrations in PBMCs than TDF/FTC as PrEP Ogbuagu, et al. 2021, which may confer a clinical benefit in terms of time to protection and adherence forgiveness, but this is preliminary evidence and further evaluation is needed. It is reasonable to assume protection at 7 days, and likely earlier. There are no data on a double dose at initiation for more immediate protection.

CAB LA: CAB LA is estimated to be protective 7 days after the initial injection Han(a), et al. 2024. If switching from oral PrEP, individuals should be advised to continue oral PrEP for an additional 7 days to maintain protection while CAB LA levels are rising, otherwise counsel individuals on additional HIV prevention techniques, including barrier protection and abstinence, during this time.

SC LEN: Rapid increases have been observed in plasma concentrations of LEN after the initial oral loading dose and first injection, reaching therapeutic levels within 2 hours after the second oral loading dose on day 2 Gilead 2025; Jogiraju, et al. 2025, and it is reasonable to assume protection at that point. Individuals initiating SC LEN who are not already using PrEP should be counseled on using additional HIV prevention techniques, including barrier protection and abstinence, during the oral loading period. Individuals switching from oral PrEP to SC LEN are protected from HIV on the day of the initial injection. If the second oral loading dose is missed, the time to protection increases to up to 28 days Gilead 2025.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Choosing and Prescribing a PrEP Regimen

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Choice of Regimen

TDF/FTC

TAF/FTC

Patients With HBV

CAB LA

SC LEN

|

Resources: Checklist 1: Key Factors in Choice of PrEP Regimen; Checklist 2: Assessment and Counseling Before PrEP Initiation Abbreviations: CAB LA, long-acting injectable cabotegravir (Apretude); CrCl, creatinine clearance; HBV, hepatitis B virus; IM, intramuscular; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; MSM, men who have sex with men; oral CAB, oral cabotegravir (Vocabria); PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; SC LEN, subcutaneous lenacapavir (Yeztugo); TAF/FTC, tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy); TDF/FTC, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada). |

Preferred Oral Regimen for Daily Dosing: TDF/FTC

TDF/FTC is the preferred oral HIV PrEP regimen because of its proven efficacy and safety in clinical trials, suitability for use in all populations, including individuals who inject drugs, and cost, which is significantly lower than that of TAF/FTC. However, for adults with preexisting renal disease or osteoporosis and for adolescents aged 19 years or younger, TAF/FTC is the preferred oral regimen (see discussion below).

Daily dosing: The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved dosing of TDF/FTC as PrEP is 1 tablet daily by mouth with or without food FDA 2024.

Common adverse effects: In clinical trials of TDF/FTC as PrEP, the most common adverse effects were nausea, headache, abdominal pain, and dizziness, which were mild and short-lived McCormack, et al. 2016; Thigpen, et al. 2012; Grant, et al. 2010. Most adverse effects peaked at 1 month and generally resolved within 3 months Glidden, et al. 2016. In a study comparing TAF/FTC and TDF/FTC as PrEP, both regimens were well tolerated, with diarrhea the only treatment-related adverse effect in >10% of individuals in either study arm Mayer, et al. 2020.

Renal impairment and loss of bone density: Both renal impairment and loss of bone density have been observed in individuals taking TDF/FTC as HIV treatment, predominantly in studies of TDF/FTC combined with a third drug containing the pharmacokinetic booster ritonavir or cobicistat. Studies comparing unboosted TDF/FTC and TAF/FTC for HIV treatment found no difference in adverse events between the 2 regimens Hill, et al. 2018. A meta-analysis of 13 trials of TDF/FTC used as PrEP found no difference in serious adverse events between TDF/FTC and placebo but did find a borderline statistically significant difference in creatinine elevation of all grades when adding in grade 1 and 2 elevations Pilkington, et al. 2018.

The DISCOVER study, which compared TDF/FTC with TAF/FTC as PrEP, found a small but statistically significant difference between biomarkers of renal and bone dysfunction favoring TAF/FTC, although no difference was found in clinical adverse outcomes Mayer, et al. 2020. Although renal dysfunction is uncommon in individuals taking TDF/FTC as PrEP, and especially those who are younger than 50 years Gandhi, et al. 2016, regular laboratory monitoring is necessary during use of TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC (see Table 4: Recommended Routine Laboratory Testing for Individuals Using PrEP). If an increase in serum creatinine or a decrease in calculated CrCl is observed, evaluate potential causes other than TDF use. Discontinuation or interruption of TDF/FTC as PrEP is appropriate if other causes are ruled out or if CrCl drops to <50 mL/min (confirmed on 2 readings) for any reason. TAF/FTC is indicated for sexual exposures when CrCl ≥30 mL/min. When appropriate, on-demand dosing of TDF/FTC can also be considered to decrease drug exposure for individuals with borderline renal function.

Bone density losses with TDF/FTC as PrEP are minimal, have not been associated with bone fractures, and are reversible in individuals aged 20 years and older Havens, et al. 2020; Spinelli, et al. 2019. However, bone loss did not completely reverse in individuals aged 19 years and younger Havens, et al. 2020; therefore, TDF/FTC is not the preferred option in this age group (see Appendix B: Studies That Support the Use of PrEP in Different Populations > Adolescents > Oral PrEP).

Alternative Oral Regimen for Daily Dosing: TAF/FTC

TAF/FTC is an alternative oral HIV PrEP regimen for all sexual exposures. However, it is the preferred oral regimen (for all sexual exposures) for individuals with preexisting renal disease or osteoporosis and for individuals aged 19 years and younger. TAF/FTC may also be preferable when there are multiple risk factors for renal disease or osteoporosis.

Daily dosing: The FDA-approved dosing of TAF/FTC as PrEP is 1 tablet daily by mouth with or without food FDA(b) 2025. On-demand dosing has not been studied for TAF/FTC.

TAF/FTC for receptive vaginal exposure: Based on the PURPOSE 1 trial results showing 89% lower rates of HIV acquisition in cisgender women who took 2 or more doses per week Kiweewa, et al. 2025, use of TAF/FTC is appropriate for receptive vaginal sex in those whom TDF/FTC is not appropriate, tolerated or desired.

Common adverse effects: As noted above, in a study comparing TAF/FTC and TDF/FTC as PrEP, both regimens were well tolerated, with diarrhea the only adverse effect in >10% of individuals in either arm Mayer, et al. 2020.

Managing Adverse Effects of Oral PrEP

Two weeks after oral PrEP initiation, follow up with the individual either in person or by telephone to assess and address adverse effects and offer advice for management until they abate. Gastrointestinal adverse effects can be alleviated by taking PrEP medications with food or antidiarrheal agents, anti-gas medications, and antiemetics. In the iPrEx and Partners trials of TDF/FTC as PrEP, rash was not reported as a common adverse effect Mujugira, et al. 2016; Grant, et al. 2014; Grant, et al. 2010. Assess individuals who develop a rash while taking TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC as PrEP for syphilis and acute HIV Apoola, et al. 2002.

Alternative Oral Dosing: On-Demand PrEP

On-demand (also called intermittent or event-driven) PrEP, taking medication before and after sex instead of daily, is not FDA-approved, but strong evidence for the efficacy of on-demand dosing in cisgender MSM is based on results of the IPERGAY and Prevenir studies.

Background: The IPERGAY and Prevenir studies found that 2-1-1 dosing effectively prevented HIV acquisition in MSM Molina, et al. 2022; Molina, et al. 2015. Successful on-demand PrEP requires planning ahead for sex by at least 2 hours. Data on daily dosing of TDF/FTC are more robust than for on-demand dosing, with longer follow-up. However, the preferred dosing strategy is that which fits best into the individual’s lifestyle. Clinicians should review the individual’s usual sex planning practices and ensure they understand the complex on-demand dosing schedule. Switching between daily and on-demand PrEP as sexual activity changes is an appealing, evidence-based option for some individuals Molina, et al. 2022; Hoornenborg(b), et al. 2017. On-demand dosing of TDF/FTC is not recommended for blood exposures through injection drug use or in individuals with HBV.

Earlier studies have shown that estrogen use may lower tenofovir levels in the plasma of transgender women compared with cisgender men, but more recent studies call these findings into question (see Appendix B: Studies That Support the Use of PrEP in Different Populations > Transgender women). The PREVENIR and IPERGAY studies included too few transgender women who have sex with men to prove effectiveness in this population Molina, et al. 2022; Molina, et al. 2015. However, the lack of drug interactions with gender-affirming hormone therapy supports the use of on-demand PrEP in transgender women.

There are no studies of on-demand PrEP for receptive vaginal sex. Modeling data suggest that although tenofovir levels are lower in the female genital tract than in rectal tissue, FTC levels are high enough to offer significant protection at the tissue level within 2 hours of dosing. Tenofovir levels decrease in the female genital tract faster than in rectal tissues, but the addition of 1 more day of TDF/FTC increases protection from 85% to an estimated 93% to 98% Engel, et al. 2025. Systemic drug levels of TDF/FTC measured in PBMCs reflect intracellular concentrations necessary to inhibit HIV replication, regardless of tissue concentrations in the female genital tract. If individuals who are at risk of HIV exposure through receptive vaginal sex prefer an on-demand option instead of daily oral or injectable PrEP, it is reasonable to engage them in shared decision-making about on-demand PrEP (with an additional day of dosing) while awaiting clinical trial data.

Dosing strategies:

- On-demand dosing for rectal and penile exposures: TDF/FTC is taken as a “2-1-1” regimen:

- 2 to 24 hours before sex: Take 2 TDF/FTC tablets (closer to 24 hours is preferred), followed by

- 24 hours after sex: Take 1 TDF/FTC tablet, then

- 48 hours after sex: Take 1 TDF/FTC tablet

- If sex occurs again: Take 1 TDF/FTC tablet daily until 48 hours after the last sex act, effectively becoming daily PrEP for as long as sex continues.

- On-demand dosing for receptive vaginal exposures: TDF/FTC is taken as a “2-1-1-1” regimen:

- 2 to 24 hours before sex: Take 2 TDF/FTC tablets (closer to 24 hours is preferred), followed by

- 24 hours after sex: Take 1 TDF/FTC tablet, then

- 48 hours after sex: Take 1 TDF/FTC tablet

- 72 hours after sex: Take 1 TDF/FTC tablet

- If sex occurs again: Take 1 TDF/FTC tablet daily until 72 hours after the last sex act, effectively becoming daily PrEP for as long as sex continues.

- On-demand dosing cannot be recommended for protection against blood exposures.

There are no data to guide decisions on the use of on-demand PrEP for neovaginal or neopenile HIV exposures.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Injectable Regimen: CAB LA Every 2 Months

When CAB LA is preferred: Because of its statistically superior efficacy to oral PrEP regimens and its protection against HIV through all types of sexual exposure, CAB LA is a preferred PrEP agent for all adults and adolescents weighing ≥35 kg who are open to injectable PrEP. CAB LA is an advantageous option when oral medication poses a challenge to PrEP use. TDF/FTC (or TAF/FTC if available same day) can be used as an alternative therapy for same-day initiation when oral CAB or CAB LA is not immediately available because of insurance or logistics issues. Overlapping 7 days of oral TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC with CAB initiation can be used to maintain protection against HIV while CAB levels are attaining steady-state.

Oral CAB lead-in: In clinical trials of CAB LA, a 5-week oral CAB lead-in was administered to rule out adverse effects before individuals received a long-acting injection Delany-Moretlwe, et al. 2022; Landovitz, et al. 2021. Although there are no data on the safety or efficacy of CAB LA when used for PrEP without an oral lead-in, in clinical trials of long-acting injectable CAB plus rilpivirine (CAB/RPV LA) for HIV treatment, omission of the oral lead-in was safe and did not interfere with achievement of adequate plasma CAB levels when injections were initiated Orkin, et al. 2021. There were no CAB safety concerns identified during the oral lead-in phase in trials of CAB/RPV LA as HIV treatment Rizzardini, et al. 2020 or in trials of CAB LA as PrEP Delany-Moretlwe, et al. 2022; Landovitz, et al. 2021. As a result, the oral lead-in phase for CAB LA as PrEP is now optional.

Some care providers or individuals initiating PrEP who are concerned about tolerability may prefer an oral CAB lead-in. An important consideration in such cases is the potential risk of HIV acquisition for individuals who may struggle with adherence to daily oral medication. Of note, 3 of the 12 incident HIV infections in individuals using CAB as PrEP in the HPTN 083 study were acquired during the oral lead-in phase Marzinke(a), et al. 2021. Ongoing daily oral CAB is not FDA-approved or recommended as PrEP.

CAB LA injections: See Box 2, below, for details on the dosing, preparation, and administration of CAB LA as PrEP.

| Box 2: Dosing, Preparation, and Administration of Long-Acting Injectable Cabotegravir as Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis [a] |

Initiation and continuation doses:

Preparation and administration:

|

|

Note: |

Adverse effects: In the clinical trials noted above, CAB LA as PrEP was well tolerated. Adverse reactions observed in at least 1% of participants included injection site reactions, diarrhea, headache, pyrexia, fatigue, sleep disorders, nausea, dizziness, flatulence, abdominal pain, vomiting, myalgias, rash, decreased appetite, somnolence, back pain, and upper respiratory tract infection; however, almost all were grade 1–level effects Delany-Moretlwe, et al. 2022; Landovitz, et al. 2021. The most common adverse effects were injection site reactions in 81% of HPTN 083 study participants and 32% of HPTN 084 study participants. Reactions were mostly mild or moderate in intensity and decreased in frequency and intensity over time. Median onset was 1 day after injection in the HPTN 083 trial and lasted a median of 3 days. Discontinuations due to injection site reactions were rare and occurred at a rate of 2.4% in the HPTN 083 trial and 0.0% in the HPTN 084 trial. Other studies have reported a strong preference for long-acting injectable medications despite injection site reactions Tolley, et al. 2020; Murray, et al. 2018.

Drug-drug interactions: Strong inducers of cytochrome 450 (CYP), uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferase (UGT)1A and P-glycoprotein (P-gp) can significantly decrease CAB levels. Although the risk of drug-drug interactions when combining CAB LA with most medications used in primary care is low, there is a risk of reduced CAB drug concentrations when used concurrently with certain antiseizure drugs such as carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital (and primidone), phenytoin, as well as with rifamycins. For guidance in managing CAB LA drug-drug interactions, consult the following resources:

- NYSDOH AI Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From HIV Prevention to Treatment

- University of Liverpool HIV Drug Interactions

Metabolic effects: Mild weight gain was observed in MSM and transgender women receiving CAB LA as PrEP compared with TDF/FTC, but there was no significant difference in weight between the 2 study arms in cisgender women, and there was no significant effect on lipid levels Delany-Moretlwe, et al. 2022; Landovitz, et al. 2021.

Oral CAB as bridge therapy: Oral CAB can be used as bridge therapy when it is anticipated that a CAB LA injection will be missed. Oral CAB is currently only available from a central pharmacy in collaboration with ViiV Healthcare. TDF/FTC (or TAF/FTC if appropriate) can also be used as bridge therapy when logistics impede timely access to oral CAB.

Alternative sites of injection: Data on alternative sites of injection are insufficient. Thigh injections into the vastus lateralis muscle were associated with a 10% decrease in bioavailability and more rapid decline in drug levels Han(b), et al. 2024.

Managing missed injections: As mentioned above, CAB LA is given every 2 months, with a window period of 1 week before or after the prior injection. Missed injections are bridged with oral PrEP.

- Planned missed injection (>5 weeks since initiation injection or >9 weeks since last continuation injection): If an individual misses their CAB LA injection for a planned reason, initiate oral PrEP (oral CAB, TDF/FTC, or TAF/FTC) beginning when the injection is due and continuing until CAB LA can be administered. If it has been more than 12 weeks since their last injection, the individual can stay on oral PrEP or restart CAB LA injections with the 4-week loading dose.

- Unplanned missed injections: If an individual misses their CAB LA for an unplanned reason, determine why the individual is unable to return and refer them for appropriate services as needed. Offer the individual oral PrEP until injections can be resumed (if appropriate) and guidance as noted above for planned missed injections.

Discontinuing CAB LA: CAB levels begin to decline in the body 2 months after the last injection but persist and slowly decline over a median of 43.7 weeks for men and 67.3 weeks for women Landovitz, et al. 2020. During this time there are increasingly lower CAB levels that will not protect from HIV infection. Educate individuals receiving CAB LA as PrEP on the medication “tail” and provide individualized guidance on alternative PrEP options and prevention planning if HIV risk continues. If risk is ongoing, oral PrEP should be continued for at least 1 year to prevent the acquisition of INSTI-resistant HIV. However, it is reassuring that none of the individuals in the HPTN 083 study who acquired HIV during the tail phase had INSTI resistance-associated mutations Landovitz, et al. 2021.

Diagnosing HIV in individuals receiving CAB LA: Diagnosing HIV seroconversion in individuals receiving CAB LA can be challenging. For discussion of long-acting early viral inhibition (LEVI) syndrome with potential delayed HIV positivity, altered presentation of acute HIV, and altered testing algorithms while using CAB LA as PrEP, see guideline section Managing a Positive HIV Test Result > Ambiguous HIV Test Results > LEVI syndrome.

Injectable Regimen: SC LEN Every 6 Months

When SC LEN is preferred: Because of its statistically superior efficacy to oral PrEP regimens and its protection against HIV through all types of sexual exposure, SC LEN is a preferred PrEP agent for all adults and adolescents weighing ≥35 kg who are open to injectable PrEP.

Dosing: See Box 3, below, for details on the dosing, preparation, and administration of SC LEN as PrEP.

| Box 3: Dosing, Preparation, and Administration of Subcutaneous Lenacapavir as Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis [a] |

How supplied:

Initiation dose:

Continuation dose:

Preparation and administration:

|

|

Note: |

Adverse effects: The most common and expected adverse effects associated with SC LEN are injection site reactions (ISRs), which may include pain, erythema, swelling, nodules, induration, and pruritus. Individuals receiving SC LEN as PrEP should be counseled to expect potential discomfort, induration, and subcutaneous nodules in the first week after the injection. SC LEN injections commonly create persistent subcutaneous nodules, which in the PURPOSE-2 study lasted a median of 183 days Kelley, et al. 2025. Although they are generally painless, the nodules can be palpated and sometimes visible depending on the physique of the individual. ISRs rarely led to discontinuation Kelley, et al. 2025; Bekker, et al. 2024. Proper injection technique (using ice packs at the site before injection and injecting at a 90° angle) can significantly decrease the incidence and intensity of ISRs FDA(d) 2025; Kelley, et al. 2025.

Where to inject: The FDA label lists the preferred site of administration as the abdomen, with the thigh an accepted alternate site. However, pharmacokinetic data show similar or higher LEN levels for upper arm and thigh injections Lat, et al. 2023 and safety data show similar or lower rates of ISRs with thigh, upper arm, and gluteal region injections Saunders, et al. 2024, compared with abdomen injections. These data support using alternate injection sites based on patient preference.

Drug-drug interactions: Because LEN is a substrate and moderate inhibitor of CYP3A4 and a substrate of P-gp, the potential for drug-drug interactions associated with the use of SC LEN as PrEP should be carefully considered. Although the risk of drug-drug interactions when combining LEN with most medications used in primary care is low, there is a risk of reduced LEN drug concentrations when used concurrently with CYP3A4 or P-gp inducers. Examples of common CYP3A4 inducers can be remembered with the mnemonic COPPER: Carbamazepine, Oxcarbazepine, Phenobarbital (and primidone), Phenytoin, Enzalutamide, and Rifampin (also rifabutin and rifapentine). Although not a complete list, these are the most common CYP3A4 inducers used in clinical practice.

LEN increases drug concentrations of gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB), ketamine, benzodiazepines, fentanyl, and nitazenes, making adverse effects and overdose of these drugs when used concurrently with SC LEN a concern. LEN also increases drug concentrations of PDE5 inhibitors, which are used to treat erectile dysfunction. Taking amyl nitrates (“poppers”) with PDE5 inhibitors is contraindicated because of the risk of a severe drop in blood pressure, which would be more likely with concomitant SC LEN use. It is important that clinicians discuss the risk of and effects of drug-drug interactions with individuals receiving SC LEN.

Dosing of SC LEN with concomitant strong or moderate CYP3A4 inducers: Current FDA prescribing information for SC LEN for HIV prevention provides recommendations for supplemental dosing with LEN injections and/or oral tablets to offset potential interactions; these recommendations vary depending on whether a strong or a moderate CYP3A4 inducer is being added to LEN. For guidance in determining the degree of induction from CYP3A4 (and other isoenzymes of CYP450) when managing drug-drug interactions, consult the following resources:

- NYSDOH AI Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From HIV Prevention to Treatment

- FDA Drug Development and Drug Interactions, Table of Substrates, Inhibitors and Inducers (may not contain all medications identified as CYP3A4 inducers)

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents With HIV > Drug-Drug Interactions

- University of Liverpool HIV Drug Interactions

Note that FDA recommendations for managing concurrent use of CYP3A4 inducers differ greatly in the prescribing information for LEN used as HIV prevention (Yeztugo) and LEN used for HIV treatment (Sunlenca).

| KEY POINTS |

|

Managing missed injections: As mentioned above, SC LEN is given every 6 months, with a window period of 2 weeks before or after the prior injection. Missed injections are bridged with oral LEN or another oral PrEP regimen if oral LEN is not available. For both planned and unplanned missed injections, if oral LEN is not initiated for bridging and more than 28 weeks have lapsed since the prior injection, reinitiation with oral LEN 600 mg daily for 2 days is needed in addition to LEN injections.

- Planned missed injection >14 days late (>28 weeks since the last injection): If an individual misses their LEN injection for a planned reason, initiate oral LEN 300 mg once every 7 days (beginning when the injection is due) and continue until SC LEN can be administered, up to a maximum of 6 months (26 weeks). If the injection is missed beyond 6 months (i.e., more than 52 weeks since the last injection), transition the individual to another PrEP regimen if they plan to continue PrEP (see Discontinuing SC LEN, below). If oral LEN is unavailable for bridging, prescribe another oral PrEP regimen.

- Unplanned missed injection >14 days late (>28 weeks since the last injection): If an individual misses their SC LEN injection for an unplanned reason, determine why the individual is unable to return and refer them for appropriate services as needed. Offer the individual oral LEN or another oral PrEP regimen as noted above for planned missed injections.

Discontinuing SC LEN: Levels of SC LEN begin to decline in the body 6 months after the last injection and continue to decline over the following 6 months (the medication “tail”). During this time there are increasingly lower levels of SC LEN that will not protect from HIV infection. Individuals receiving SC LEN as PrEP should be educated on the medication “tail” and provided individualized guidance on alternative PrEP options and prevention planning if HIV risk continues.

Managing a positive HIV test result: See guideline section Managing a Positive HIV Test Result. In the 2 seroconversions seen in the PURPOSE 2 study, no delay was observed in HIV antigen/antibody positivity, and viral load results were 14,100 and 934,000 copies/mL, respectively Kelley, et al. 2025. For individuals who have a positive HIV test result while receiving SC LEN as PrEP, an initial INSTI-based antiretroviral therapy (ART) regimen should be initiated (see the NYSDOH AI guideline Selecting an Initial ART Regimen).

| KEY POINT |

|

PrEP During Pregnancy

PrEP should be offered to pregnant individuals with ongoing HIV exposure, as HIV acquisition risk is higher during pregnancy and highest in the late pregnancy and early postpartum periods Thomson, et al. 2018. Risk of perinatal transmission is also significantly higher during pregnancy and breast/chestfeeding in cases of acute seroconversion Drake, et al. 2014; Singh, et al. 2012, and this committee recommends PrEP in individuals at risk while they are breast/chestfeeding. Encourage pregnant individuals to inform their obstetric and pediatric care providers when using PrEP medications or any other prescription or over-the-counter medications. Prospectively report pregnancies in individuals on PrEP to the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry.

TDF/FTC: TDF/FTC is considered safe to use during pregnancy FDA 2024. Available data suggest that TDF/FTC as PrEP does not increase the risk of congenital anomalies. Conflicting results have been observed in studies of bone mineral density in infants born to women taking TDF as a component of ART for HIV Siberry, et al. 2015; Vigano, et al. 2011. However, more recent studies of infants exposed to TDF in utero, 1 due to maternal HIV Reddy, et al. 2024 and 2 for HBV transmission prevention Wen, et al. 2020; Salvadori, et al. 2019, showed comparable bone mineral composition in exposed versus unexposed infants aged 1 to 7 years.

Infant exposure to TDF/FTC through breast milk is much lower than TDF exposure in utero; evidence to date suggests that TDF is safe during breastfeeding Liotta, et al. 2016; Ehrhardt, et al. 2015. Although data on breastfeeding effects are limited, TDF/FTC is commonly prescribed as part of an ART regimen before, during, and after pregnancy, and the benefit of preventing HIV infection and subsequent perinatal transmission among individuals at increased risk outweighs the theoretical concerns associated with prescribing TDF/FTC as PrEP during breastfeeding, pending further data.

TAF/FTC: Clinical trials, observational studies, and data from the Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry support the use of TAF/FTC in pregnancy Zeng, et al. 2025. Further, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine states that TAF/FTC has a similar safety profile to TDF/FTC for PrEP Badell, et al. 2024. TAF/FTC has been shown to be well tolerated and there have been no increased adverse pregnancy or infant outcomes in those taking TDF as PrEP or treatment for chronic HBV infection during pregnancy Heffron, et al. 2018.

CAB LA: No significant differences in maternal adverse events or pregnancy outcomes were observed between CAB LA and TDF/FTC in the HPTN 084 trial Delany-Moretlwe, et al. 2025. HPTN 084 researchers presented updated pharmacokinetic data for CAB LA as PrEP used before and during pregnancy. CAB LA was generally well tolerated. CAB LA levels declined in each trimester of pregnancy but remained above specific target levels. These findings suggest that no dose changes are needed when using CAB LA during pregnancy, although more human data are needed. None of the women who became pregnant while receiving CAB LA acquired HIV during their pregnancy. Use of CAB LA as PrEP appears to be safe during pregnancy, but data are limited. Use shared decision-making when considering whether to initiate or switch from CAB LA as PrEP for individuals who are pregnant or planning to conceive.

SC LEN: In the PURPOSE 1 study, there were 208 pregnancies and 132 live births in the SC LEN group, there were no pregnancy complications found to be related to SC LEN use, and the infant mortality rate was similar to background rates in the study region and to tenofovir-based PrEP FDA(d) 2025; Bekker, et al. 2024. No adverse effects related to SC LEN during breast/chestfeeding have been observed. Discuss potential risks and benefits and engage individuals who are or may become pregnant in shared decision-making when considering SC LEN as PrEP.

Initiating PrEP

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Preinitiation Assessment

Baseline Laboratory Testing

Same-Day Initiation

Initiating PrEP During the HIV Testing Window Following Exposure

|

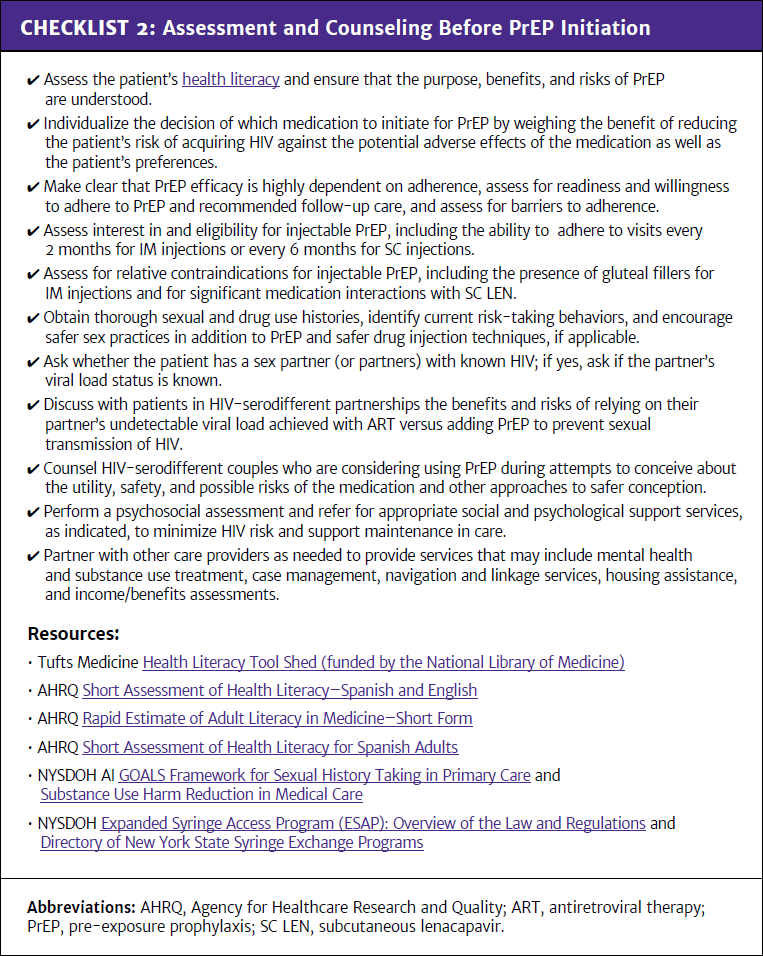

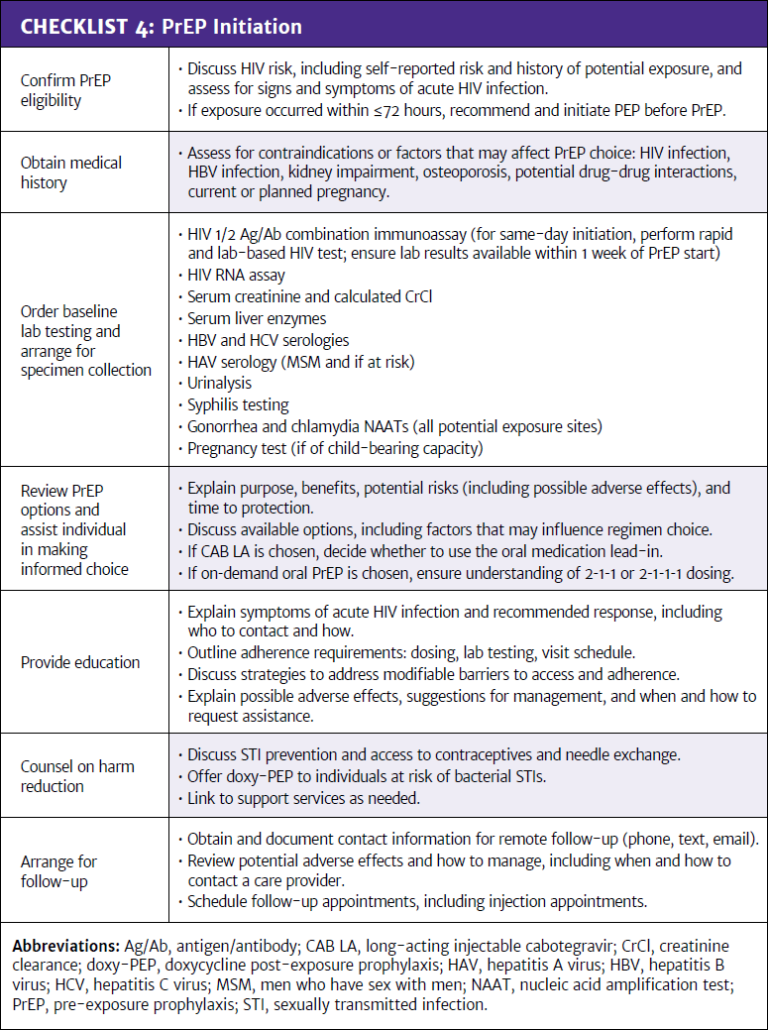

Resources: Checklist 2: Assessment and Counseling Before PrEP Initiation; Checklist 4: PrEP Initiation Abbreviations: Ag/Ab, antigen/antibody; ART, antiretroviral therapy; CAB LA, long-acting injectable cabotegravir (Apretude); CEI, Clinical Education Initiative; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis. |

Before Initiating PrEP

Assess for acute HIV infection: Before initiating PrEP, all individuals should be evaluated for potential HIV exposure in the prior 6 weeks and assessed for the flu-like symptoms of acute HIV. Both an HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab combination immunoassay and an HIV RNA test should be performed within 1 week before PrEP initiation. HIV RNA (viral load) testing is recommended at baseline to rule out acute HIV infection regardless of reported risk, as individuals may be reluctant to disclose a recent potential risk exposure. If a confirmed negative result is not available at the time of the patient’s initial visit, a rapid HIV-1/2 test should be performed for same-day PrEP initiation.

Drug-resistant virus has been found in individuals with undiagnosed HIV who initiated PrEP with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC), tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (TAF/FTC), CAB LA and subcutaneous lenacapavir (SC LEN) Kelley, et al. 2025; Molina, et al. 2022; Landovitz, et al. 2021; Cox, et al. 2020; Lehman, et al. 2015.

Perform recommended laboratory testing: Table 3, below, lists the baseline laboratory tests that should be performed before PrEP initiation. When an individual is engaged in PrEP care, primary healthcare may also be offered as indicated, including vaccinations against hepatitis A and B viruses, human papillomavirus, meningococcus, mpox, influenza, and COVID-19 (see the NYSDOH AI guidelines Primary Care for Adults With HIV and Immunizations for Adults With HIV).

| Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; Ag, antigen; anti-HBc, hepatitis B core antibody; anti-HBs, hepatitis B surface antibody; CAB LA, long-acting injectable cabotegravir (Apretude); CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CrCl, creatinine clearance; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G; SC LEN, subcutaneous lenacapavir (Yeztugo); MSM, men who have sex with men; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; TAF/FTC, tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy); TDF/FTC, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada); UCSF, University of California San Francisco.

Notes:

|

||

| Table 3: Recommended Laboratory Tests for All individuals Within 1 Week Before Initiating PrEP [a] | ||

| Purpose (rating) | Test | Comments |

| HIV status (A*) |

|

|

| Renal function (A*) | Serum creatinine and calculated CrCl |

|

| Pregnancy status (A3) | Pregnancy test for all individuals of childbearing potential |

|

| HBV infection status (A2†) | HBV serologies: HBsAg, anti-HBs, and anti-HBc (IgG or total) |

|

| Syphilis screening (A2†) | All individuals: Syphilis testing [d] | Screen for syphilis according to the laboratory’s testing algorithm. |

| Gonorrhea and chlamydia screening (A2†) |

|

|

| HCV infection status (A3) | HCV serology with reflex to RNA | Inform individuals with HCV about transmission risk and offer or refer for treatment [f]. |

| HAV infection status (good practice) | HAV serology for MSM and individuals at high risk of HAV infection [g] | Vaccinate nonimmune individuals. |

| Hepatic function (good practice) | Serum liver enzymes | Increased serum liver enzymes may indicate acute or chronic viral hepatitis infection and require further evaluation. |

| Assess for preexisting renal disease, proteinuria, and glycosuria (good practice) | Urinalysis | Only calculated CrCl is used to guide decisions regarding the use of TDF/FTC and TAF/FTC as PrEP based on renal function; however, baseline urinalysis abnormalities may indicate an increased risk of renal tenofovir toxicity. |

Assessment and Counseling Before PrEP Initiation

Engagement in primary care: PrEP is an integral part of sexual health and well-being. Developing an HIV prevention plan that includes PrEP is an opportunity to engage individuals in primary care. Clinicians can encourage age-appropriate health screenings, substance use screening and interventions, linkage to specialty services, and other health maintenance activities such as immunizations (see the NYSDOH AI guideline Immunizations for Adults With HIV). For additional information, see Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommended Adult Immunization Schedule for Ages 19 Years or Older, United States, 2025 and ACIP Recommendations: COVID-19 Vaccine and NYSDOH Health Advisory: NYSDOH Meningococcal Vaccine Recommendations for HIV-Infected Individuals and Those at High Risk of HIV Infection.

Patient education: Patient education is vital to shared decision-making and the success of PrEP as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention plan. Educate PrEP candidates about its risks and benefits and the choice of oral versus injectable PrEP. Discuss individual preferences, needs, and circumstances. Adherence and persistence improve when individuals participate in medication-related decisions and are informed about the strong efficacy of PrEP when taken as directed Grinsztejn, et al. 2025 (see guideline section Adherence, below). Education provided in the individual’s native or preferred language and tailored to the individual’s level of comprehension and health literacy will help ensure understanding of the benefits and potential adverse effects, the need for adherence, regular monitoring, the process of obtaining refills for oral PrEP, payment and payment assistance, and how safer sex or drug injection practices decrease the risk of pregnancy or of acquiring HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (see Be in the KNOW > Sex and HIV and NYSDOH Syringe Access and Disposal).

Sex and drug use histories: A detailed HIV risk assessment includes obtaining a patient’s sexual history and drug use history and having a frank, open, and nonjudgmental discussion of risk-related behaviors. As indicated, this discussion may also include offering further counseling and referrals, such as for substance use treatment (see NYSDOH Office of Addiction Services and Supports > Treatment and guidelines on Substance Use Care).

Viral load status of sex partner(s) with HIV: The antiretroviral therapy (ART) and viral load status of a sex partner with HIV may inform the discussion of risk. Sexual transmission of HIV does not occur when an individual with HIV has a persistently undetectable HIV viral load; nonetheless, an individual without HIV in a serodifferent partnership who does not have HIV may still elect to use PrEP Rodger, et al. 2016 (see discussion below). If the patient’s partner has detectable virus and genotypic test results are unavailable, knowledge of the partner’s ART regimen may be helpful. HIV acquisition risk is increased when an individual is exposed to HIV that is resistant to the components of their PrEP regimen Gibas, et al. 2019; Knox, et al. 2017. The potential for drug resistance is an important consideration when choosing a PrEP regimen. If there is a risk for drug resistance in a sex partner with HIV, choose a PrEP option to which said partner is not known to be resistant.

HIV-serodifferent couples: As mentioned above, in an HIV-serodifferent partnership the partner who does not have HIV may decide to use PrEP even if the partner with HIV has achieved an undetectable viral load with ART. Although this supplemental protection is likely unnecessary in light of the finding that undetectable = untransmittable (U=U), PrEP can be discussed as an additional option for HIV prevention. The partner without HIV may choose to take PrEP for other reasons, including if they have additional sex partners, are unsure of a sex partner’s viral load or ability to maintain viral suppression, or feel more secure about and in control of their sexual health with the added protection of PrEP. In September 2017, the NYSDOH endorsed the U=U consensus statement from the Prevention Access Campaign. For more information, see Appendix B: Studies That Support the Use of PrEP in Different Populations > HIV-serodifferent couples and NYSDOH AI U=U Guidance for Implementation in Clinical Settings.

Reproductive counseling: Inquire about the individual’s reproductive plans and provide preconception counseling when indicated. Determine whether they or their partner is pregnant or breast/chestfeeding, intends to conceive, or is currently using hormonal or other contraception in addition to condoms Bujan and Pasquier 2016; Lampe, et al. 2011; Vernazza, et al. 2011. Counsel HIV-serodifferent couples who are considering the use of PrEP during attempts to conceive about the utility, safety, and possible risks of the medication (see guideline section Choosing and Prescribing a PrEP Regimen > PrEP During Pregnancy).

Psychosocial assessment: Assessments of psychosocial needs, strengths, challenges, mental health, and substance use are integral to good general medical practice. In the case of someone prescribed PrEP, such assessments enable clinicians to identify modifiable barriers to adherence and provide services and referrals to support adherence and retention in care.

PrEP after PEP: Individuals who remain at increased risk of HIV exposure after completing a course of non-occupational post-exposure prophylaxis (nPEP) and are negative for HIV at the 4-week test should be offered PrEP to begin immediately after the last dose of nPEP. Giving a prescription for the first month of PrEP at the time PEP is prescribed can significantly increase access to and uptake of PrEP Cockbain, et al. 2022.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Same-Day PrEP Initiation

Once laboratory specimens are obtained (see Table 3, above) PrEP may be initiated while test results are pending as long as results will be available and addressed within 7 days and a rapid HIV test result is negative and if the individual has not had symptoms or signs of acute HIV in the prior 6 weeks, has no history of renal disease, and no risk exposures in the past 72 hours requiring PEP. Same-day PrEP initiation has been shown to be safe, and delayed PrEP initiation has been associated with a significant rate of loss to follow-up Kamis, et al. 2019; Mikati, et al. 2019. Same-day PrEP initiation may engage individuals more fully in care and reduce HIV exposures while test results are pending and encourages immediate attention to insurance coverage for PrEP or identification of other options for payment if needed.

Same-day PrEP initiation also risks starting a nonsuppressive ART regimen in someone with HIV. However, if laboratory results are available promptly, the PrEP regimen for an individual who tests positive for HIV can be intensified to a fully suppressive ART regimen and a referral for HIV care can be made. If the baseline HIV testing result is positive after the individual has received the first CAB LA injection, the clinician should consult with an experienced HIV care provider regarding the best way to intensify the PrEP regimen to a fully suppressive ART regimen (see guideline section Managing a Positive HIV Test Result). If a patient has a positive HIV test result after receiving the first dose of SC LEN, they should be placed on any preferred regimen as per HIV treatment guidelines.

TAF/FTC may require a prior authorization, which can make same-day initiation a challenge, but generic TDF/FTC is usually available for same-day initiation. If prior insurance authorization is required, same-day CAB initiation (oral or injection) and SC LEN may not be possible. Implementation challenges such as stocking and storing injectable medications in advance may also be prohibitive. If same-day initiation of CAB LA or SC LEN is not possible, an oral PrEP regimen can be an interim option while barriers to accessing injectable PrEP are addressed.

Although delays such as insurance barriers may impede PrEP initiation, the overall goal should be same-day initiation in individuals without renal disease, need for PEP, or signs or symptoms of acute HIV.

Initiating PrEP during the HIV testing window period: The window period is the time between when an individual has acquired HIV and when a diagnostic test can detect infection. The median time to positivity is 12 days for an HIV viral load test and 18 days for a laboratory-based HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab combination immunoassay; however, the 99th percentile for a positive test is 33 days for an HIV viral load test and 42 days for a laboratory-based HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab combination immunoassay Delaney, et al. 2017. Clinicians should not defer initiation of PrEP in candidates who, based on their reported sexual and drug use exposures, may be in the window period for seroconversion; doing so risks additional exposures and significant delays in PrEP initiation. Repeat HIV testing 1 month after PrEP initiation to help identify potentially positive individuals in a timely manner (see guideline section Ongoing Laboratory Testing).

| KEY POINTS |

|

Adherence

Challenges: Adherence remains a critical factor for oral PrEP effectiveness and is difficult for some individuals because of a range of intersecting factors, including pill size, tolerability, privacy concerns, PrEP-related stigma, neurocognitive impairment, mental health conditions, substance use, history of trauma, personal beliefs, travel, occupational demands, and health literacy. Although once-daily and on-demand oral PrEP dosing options are available, real-world experience and research continue to show adherence challenges for certain populations. Effective HIV prevention with TDF/FTC requires at least 4 doses per week Engel, et al. 2025; Grant, et al. 2014, and TAF/FTC effectiveness was found to be similar to TDF/FTC based on adherence Kiweewa, et al. 2025.

Timely injections are essential for long-acting injectable PrEP, as missed and delayed injections can cause viral breakthrough Landovitz, et al. 2021.

Strategies for adherence support: For oral PrEP, strategies to support and improve adherence include increasing visit frequency or follow-up contact, particularly for populations such as adolescents in whom adherence declined when visits shifted from monthly to quarterly Hosek, et al. 2017. Individualizing assessment of adherence barriers and incorporating peer support can also reinforce medication and appointment adherence Goodreau, et al. 2018; Jenness, et al. 2016.

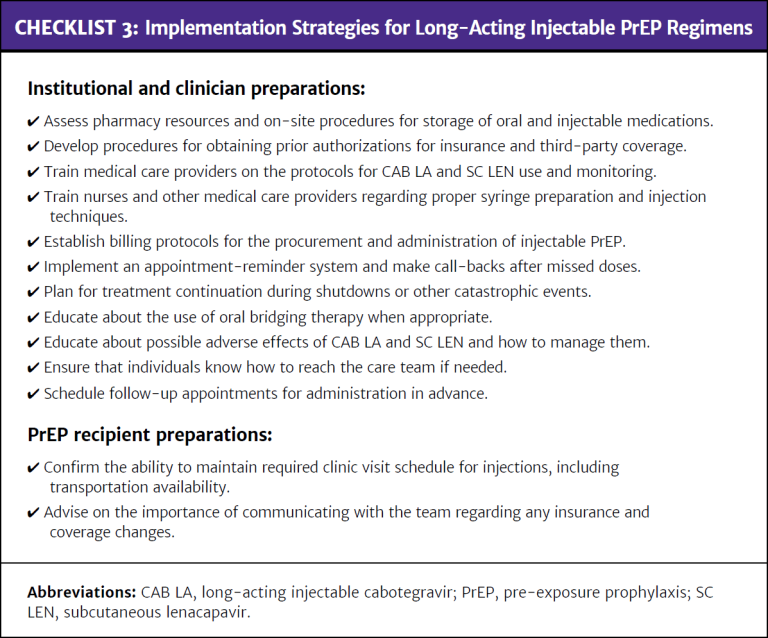

For those unable or unwilling to maintain adherence to daily oral PrEP despite support efforts, long-acting injectable PrEP is an additional preferred PrEP option. Studies indicate strong interest in injectable PrEP among the general population and key subgroups Grinsztejn, et al. 2025; Philbin, et al. 2021; Koren, et al. 2020; Rael, et al. 2020. Injection appointment reminders and ongoing counseling on the importance of on-time injections are crucial to effective injectable PrEP programs.

If injectable PrEP is not desired or is not an option, alternative options should be considered, including on-demand PrEP or intermittent use (e.g., during periods of higher risk). If these options are not feasible, clinicians may consider discussing PrEP discontinuation alongside other HIV prevention strategies that align better with the patient’s needs and preferences.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Ongoing Laboratory Testing

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Ongoing Laboratory Testing

HIV Testing

Renal Function Testing

STI Screening

HCV Screening

Pregnancy Screening

|

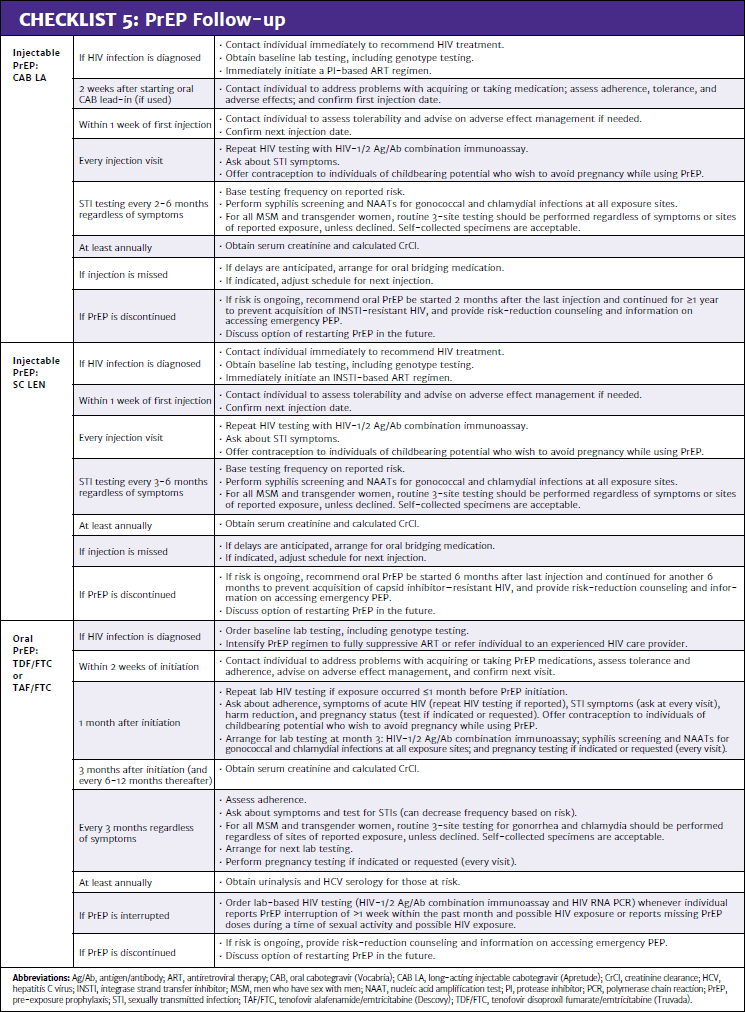

Resource: Checklist 5: PrEP Follow-Up Abbreviations: Ag/Ab, antigen/antibody; CrCl, creatinine clearance; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; HCV, hepatitis C virus; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection; TAF/FTC, tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy); TDF/FTC, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada). |

Services for follow-up and monitoring of individuals receiving PrEP are part of a comprehensive HIV prevention plan: routine HIV testing; risk-reduction counseling; access to condoms and syringes; STI, mental health, and substance use screening; and referral for treatment when indicated.

Table 4, below, lists the laboratory tests that should be performed for individuals using oral or injectable PrEP.

| Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; Ag, antigen; CAB LA, long-acting injectable cabotegravir (Apretude); CrCl, creatinine clearance; HCV, hepatitis C virus; SC LEN, subcutaneous lenacapavir (Yeztugo); oral CAB, oral cabotegravir (Vocabria); PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection; TAF/FTC, tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (Descovy); TDF/FTC, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (Truvada).

Notes:

|

|||

| Table 4: Recommended Routine Laboratory Testing for Individuals Using PrEP | |||

| Test | Laboratory Testing Indications | ||

| All PrEP Regimens | Oral PrEP: TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC |

Injectable PrEP: CAB LA or SC LEN |

|

| HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab combination immunoassay [a] |

|

|

|

| HIV RNA assay [a] | When a patient has symptoms of acute HIV [b] (A2) |

|

|

| Serum creatinine and calculated CrCl | — |

|

At least annually (A3) |

| STI (gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis) screening (A2†) Note: Screening can be less frequent in those at lower risk |

Ask about symptoms at every visit; if present, perform diagnostic testing and treat as indicated | Every 3-6 months based on reported risk |

|

| HCV serology [d] | At least annually if at risk (A3) | — | — |

| Pregnancy test in individuals of childbearing potential |

|

— | — |

| Urinalysis | — | Annually (B3) | — |

Download Table 4: Recommended Routine Laboratory Testing for Individuals Using PrEP Printable PDF

HIV Testing

For individuals using PrEP, routine HIV testing is recommended for early detection of PrEP failure. None of the available regimens are adequate for treating acute or chronic HIV infection. Continued use of only TDF/FTC, TAF/FTC, long-acting injectable cabotegravir (CAB LA), or subcutaneous lenacapavir (SC LEN) in the presence of HIV infection may lead to viral resistance to these drugs.

Routine HIV testing with oral PrEP: A quarterly (every 3 months) HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab combination immunoassay is recommended for individuals taking TDF/FTC or TAF/FTC as PrEP. Quarterly HIV RNA testing is not needed for individuals who report consistent adherence to oral PrEP.