What is U=U?

Date of current publication: April 5, 2023

Lead authors: Shauna H. Gunaratne, MD, MPH, and Jessica Rodrigues, MS

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 21, 2019

People who achieve and maintain an undetectable HIV viral load do not sexually transmit HIV.

This scientific finding, called “Undetectable = Untransmittable,” or “U=U,” has been promoted as a health equity initiative by the Prevention Access Campaign since 2016 and has been endorsed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the New York City Health Department, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH), and many other health departments and experts. U=U asserts that individuals who keep their viral load below the level of assay detection (typically HIV RNA <20 copies/mL) do not pass HIV through sex. Leading scientists have assessed the evidence base as “scientifically sound” Eisinger, et al. 2019.

As emphasized in the NYSDOH U=U Policy Statement, the U=U concept is a “driving force to accelerate the achievement of New York State’s Ending the Epidemic goals.” Specifically, U=U aligns with numerous efforts to dismantle HIV-related stigma and improve the health, well-being, and self-esteem of all people living with HIV, particularly by removing fear from their sexual and romantic relationships and combating the isolation they may experience. The statement further elaborates: “Endorsing U=U opens a new and hopeful chapter in New York State’s HIV epidemic, creating unprecedented opportunities for New Yorkers living with HIV and the institutions that serve them.”

Evidence Base Supporting U=U

Evidence from the last 3 decades has established that adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART) suppresses viral replication, improves the health of people with HIV, and reduces the risk of sexual transmission. These data have accumulated from a randomized clinical trial, observational cohort studies, and ecological studies correlating incidence and viral suppression rates in communities.

There is an overwhelming body of evidence indicating that people who achieve and maintain viral suppression (HIV RNA <200 copies/mL) do not transmit HIV through sex Eisinger, et al. 2019. The HPTN 052 randomized clinical trial and 3 observational cohort studies, PARTNER, PARTNER 2, and Opposites Attract, evaluated the effect of viral suppression in preventing HIV transmission Rodger, et al. 2019; Bavinton, et al. 2018; Cohen, et al. 2016; Rodger, et al. 2016. The studies followed thousands of male and heterosexual couples in which one partner had HIV and the other did not (i.e., serodifferent couples) and documented no genetically linked HIV transmissions when the partner with HIV was taking ART and was virally suppressed. In the PARTNER2 and Opposites Attract studies, anal sex without condoms was reported more than 88,000 times among serodifferent couples of men who have sex with men, and vaginal or anal sex without condoms was reported 36,000 times among heterosexual serodifferent couples—all without any linked transmissions.

These studies provide robust evidence that individuals do not sexually transmit HIV if they are virally suppressed (HIV RNA <200 copies/mL) or have an undetectable viral load (typically HIV RNA <20 copies/mL).

Glossary

- Viral load suppression: A measured quantitative HIV RNA level <200 copies/mL in blood

- Undetectable viral load: An HIV viral load that is below the level of detection on a specific assay, typically HIV RNA <20 copies/mL to 50 copies/mL

- Durably undetectable: An undetectable viral load maintained for at least 6 months. This indicates that an individual’s undetectable HIV viral load is stable and they will not transmit HIV through sex if they continue to adhere to treatment.

- Untransmittable: As established by various clinical trials and observational studies, individuals who maintain an undetectable viral load have so little HIV in their blood and other secretions that they have no risk of passing HIV to others through sex.

- Virologic blip: When an individual’s HIV is initially undetectable on a viral load test, then is at a low but detectable level on a repeat viral load test (usually HIV RNA of 20 to 200 copies/mL, but can be higher), and is again measured at an undetectable level shortly thereafter.

Application to Clinical Practice

The concept of U=U is grounded in the following principles Eisinger, et al. 2019:

Adherence: For HIV treatment to provide maximum benefit, it is essential that ART is taken as prescribed; the goal is to achieve an undetectable viral load. Achieving an undetectable viral load can require ART for up to 6 months. Once an undetectable viral load is achieved, continued adherence to ART is required to ensure that the virus remains suppressed so it is not transmitted through sex.

Because maintaining an undetectable viral load is foundational to the U=U strategy and may be functionally challenging for many individuals with HIV, it is recommended that consistent adherence to ART is demonstrated before relying on U=U as a sole, effective HIV prevention strategy. Consistent adherence may be confirmed with:

- Two consecutive undetectable viral load test results separated in time (e.g., by at least several weeks or more); or

- A full 6-month period during which all viral load test results are undetectable (more conservative)

If an individual stops or is inconsistent in taking ART, they may no longer have an undetectable viral load or may be at high risk of recrudescent viremia. In this scenario, transmission is possible; viral load must be undetectable for U=U to be an effective HIV prevention strategy.

Monitoring: Per NYSDOH AI guidelines, viral load testing should be performed every 4 months after an individual achieves an undetectable viral load. If viral suppression and stable immunologic status are maintained for >1 year, then viral load testing can be extended to every 6 months in select patients thereafter.

Best Practices

Adherence: U=U assumes that an individual is adherent to HIV treatment and is consistently taking antiretroviral medications as prescribed, which is the only way to maintain an undetectable viral load. Suspension of ART adherence or intermittent adherence may lead to a viral rebound, negating the effectiveness of U=U as a stand-alone HIV prevention strategy. Care providers should ask patients if anything might make it difficult for them to consistently take their medicines and address any likely barriers to adherence, which may include poverty, housing instability, and other key social factors, and offer all available support, referrals for assistance, and other interventions, along with HIV prevention strategies that do not rely on viral suppression (see NYSDOH Retention and Adherence Programs in Medical Settings).

Viral load monitoring: Care providers should follow existing NYSDOH AI guidelines for monitoring viral load in patients on treatment.

Screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) other than HIV: The use of effective alternatives to condoms to prevent HIV—including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and HIV treatment—may reduce condom use and may require more careful monitoring of other STIs, including at extragenital sites.

- Care providers should already be encouraging all patients to get tested for STIs; using U=U as a strategy to prevent HIV transmission provides an additional opportunity to remind patients of the importance of regular screening for other STIs.

- Care providers should consider offering STI screening every 3 months for all individuals with HIV who rely on U=U as a sole strategy to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV; this is the same screening frequency recommended for those taking PrEP.

Special Topics

Virologic blips and U=U: Patients on previously suppressive ART may occasionally experience low-level transient viremia (a “blip”; see definition in Glossary). Isolated blips are not considered a sign of virologic failure.

Virologic blips likely occurred in individuals participating in the HPTN 052, PARTNER, PARTNER 2, and Opposites Attract studies, yet there was no transmission from people whose measured HIV viral load was consistently suppressed. This demonstrates that people with HIV whose tested viral load levels remain undetectable or suppressed do not sexually transmit HIV, even if they have temporarily detectable but low levels of HIV during virologic blips while adherent to their medications.

HIV RNA in genital secretions and U=U: In research studies, 8% to 16% of semen samples from men with HIV had detectable virus despite undetectable HIV RNA in blood plasma Kantor, et al. 2014; Sheth, et al. 2009. A similar dynamic holds for residual virus in vaginal secretions Olesen, et al. 2016. There is no evidence that detectable virus in genital secretions while plasma viral load is undetectable is associated with transmission. Detectable virus in genital secretions likely occurred in HPTN 052, PARTNER, PARTNER 2, and Opposites Attract; however, there was no transmission from people whose measured HIV load was consistently suppressed.

U=U and HIV transmission through breastfeeding: See the NYSDOH AI guidance NYS Good Practices to Prevent Perinatal HIV Transmission > Infant Feeding.

U=U and HIV transmission through sharing of injection drug equipment: Studies demonstrate that ART greatly reduces the risk of HIV transmission through sharing of injection drug use equipment Wood, et al. 2009. However, research has not established that people with an undetectable HIV viral load do not transmit HIV through needle sharing.

U=U and needlestick injuries: Research has not established that people with an undetectable HIV viral load do not transmit HIV to people who are stuck by a needle containing their blood. HIV post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) may be indicated.

Ensuring equitable access to knowledge about U=U: Research has established that certain groups, including sexual and racial or ethnic minority groups, report decreased awareness of or are less likely to be counseled on U=U Card, et al. 2022; Grace, et al. 2022; Carneiro, et al. 2021; Rivera, et al. 2021. Care providers are encouraged to make an extra effort to ensure that all patients with HIV are made aware of the importance of U=U and its implications.

Counseling Individuals About U=U

Care providers should inform all patients of the following: “People who keep their HIV viral load at an undetectable level by consistently taking HIV medications will not pass HIV to others through sex.”

Sharing this message with all patients can help accomplish the following:

- Diminish stigma associated with having HIV

- Reduce barriers to HIV testing and treatment

- Increase HIV testing uptake

- Inform choices about whether or not to start or continue an HIV prevention method

- Increase interest in starting and staying on antiretroviral therapy (ART)

- Improve self-esteem by removing the fear of being contagious

- Support healthy sexuality regardless of HIV status

- Reduce sex partners’ concerns

Providing this message is important regardless of the patient’s current sexual activity, as many people living with HIV maintain celibacy because of the fear and anticipatory guilt of potentially transmitting HIV. This message is also important for all individuals, not only those living with HIV, to reduce overall stigma and increase uptake of HIV prevention methods and HIV testing.

Encourage patients newly diagnosed with HIV and those previously diagnosed but not taking ART to immediately start (or restart) treatment.

Explain that doing so will help them avoid damage to their body and immune system and will prevent transmission of HIV to their sex partners.

- The importance of ART should be framed primarily in terms of helping the individual with HIV maintain personal health. Prevention of transmission is a secondary, fortuitous effect of HIV self-care.

- Initiation of ART as soon as possible after diagnosis, even on the same day as diagnosis or at the first clinic visit, improves long-term outcomes, such as virologic suppression and engagement in care at 12 months Ford, et al. 2018. Extensive support is available to people living with HIV for adherence to treatment and engagement in care.

Provide the following information about U=U to patients (proposed language in italics):

- Keeping your HIV undetectable helps you live a long and healthy life.

- To get your HIV to an undetectable level and to keep it undetectable, take antiretroviral medicines as prescribed.

- It may take up to 6 months of taking HIV treatment medicines to bring your HIV down to an undetectable level.

- If your HIV is undetectable and you are taking your medications as prescribed, you can be sure you will not pass HIV through sex.

- People who keep their HIV at an undetectable level will not pass HIV to others through sex.

- If you stop taking HIV medicines, your HIV can rebound to a detectable level within 1 to 2 weeks, and you may pass HIV to your sex partners.

- Keeping your HIV at an undetectable level helps you safely conceive a child with your partner.

Counsel patients to share information about the research on U=U as follows (proposed language in italics):

In 4 research studies that involved thousands of couples, no one who was on HIV treatment and whose HIV was undetectable passed HIV to their HIV-negative sex partner.

Counsel patients with virologic blips that U=U still applies to them:

Reassure patients who may be worried or concerned about virologic blips. Explain that people who have virologic blips do not transmit HIV sexually as long as they continue to take ART consistently.

Advise patients that they can share the following personal information with current or potential sex partners:

- When they last had a viral load test and if their viral load was undetectable

- Note: Individuals should tell partners that their HIV is undetectable only if they have taken HIV medicines consistently since their last test with an undetectable viral load.

Care providers should encourage all sexually active patients and their partners, particularly those who do not use condoms consistently, to get tested regularly for bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

- Regular testing and prompt treatment can reduce transmission of bacterial STIs among individuals and throughout the population.

- It is also important to inform patients that common STIs may be asymptomatic.

Counseling Couples About U=U

Care providers should counsel all patients on strategies to maintain a healthy, fulfilling, and worry-free sex life, including the use of HIV treatment, condoms, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), and emergency post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP).

Counseling for couples in which one partner has HIV can include the following:

- HIV treatment: Couples may decide that antiretroviral therapy (ART) and an undetectable viral load for the partner with HIV provides sufficient protection against HIV transmission.

- PrEP: PrEP is a safe and effective daily pill or long-acting injection that prevents HIV infection. The partner without HIV may decide to take PrEP if they:

- Are unsure that their partner’s HIV viral load is undetectable, especially if their partner has only recently started ART

- Have more than 1 sex partner

- Feel more secure with the added perception of protection provided by PrEP

- PEP: After a possible HIV exposure (e.g., if a sex partner with HIV has not consistently taken ART or is not virally suppressed), the immediate initiation of emergency PEP can prevent HIV infection.

- Condom use: Condoms protect against other STIs, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis, and help prevent pregnancy.

Counsel patients to find a prevention strategy that works for them.

- If an individual who does not have HIV is unsure if their partner has an undetectable level of virus or is anxious about acquiring HIV, care providers should encourage that individual to choose a prevention strategy that works for them, whether that is use of PrEP, emergency PEP, condoms, or a combination of these strategies.

- Care providers should emphasize that no one should ever be compelled to have sex without condoms.

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

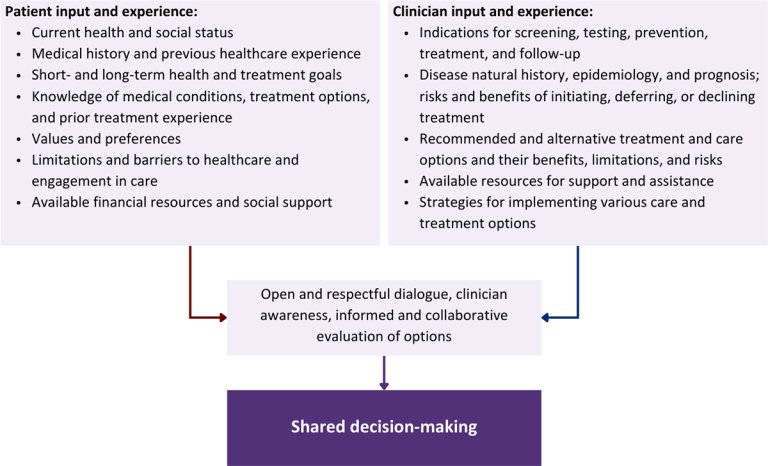

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Bavinton B. R., Pinto A. N., Phanuphak N., et al. Viral suppression and HIV transmission in serodiscordant male couples: an international, prospective, observational, cohort study. Lancet HIV 2018;5(8):e438-47. [PMID: 30025681]

Card K. G., St Denis F., Higgins R., et al. Who knows about U = U? Social positionality and knowledge about the (un)transmissibility of HIV from people with undetectable viral loads. AIDS Care 2022;34(6):753-61. [PMID: 33739198]

Carneiro P. B., Westmoreland D. A., Patel V. V., et al. Awareness and acceptability of undetectable = untransmittable among a U.S. national sample of HIV-negative sexual and gender minorities. AIDS Behav 2021;25(2):634-44. [PMID: 32897485]

Cohen M. S., Chen Y. Q., McCauley M., et al. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med 2016;375(9):830-39. [PMID: 27424812]

Eisinger R. W., Dieffenbach C. W., Fauci A. S. HIV viral load and transmissibility of HIV infection: undetectable equals untransmittable. JAMA 2019;321(5):451-52. [PMID: 30629090]

Ford N., Migone C., Calmy A., et al. Benefits and risks of rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2018;32(1):17-23. [PMID: 29112073]

Grace D., Stewart M., Blaque E., et al. Challenges to communicating the Undetectable equals Untransmittable (U=U) HIV prevention message: healthcare provider perspectives. PLoS One 2022;17(7):e0271607. [PMID: 35862361]

Kantor R., Bettendorf D., Bosch R. J., et al. HIV-1 RNA levels and antiretroviral drug resistance in blood and non-blood compartments from HIV-1-infected men and women enrolled in AIDS clinical trials group study A5077. PLoS One 2014;9(4):e93537. [PMID: 24699474]

Olesen R., Swanson M. D., Kovarova M., et al. ART influences HIV persistence in the female reproductive tract and cervicovaginal secretions. J Clin Invest 2016;126(3):892-904. [PMID: 26854925]

Rivera A. V., Carrillo S. A., Braunstein S. L. Prevalence of U = U awareness and Its association with anticipated HIV stigma among low-income heterosexually active black and latino adults in New York City, 2019. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2021;35(9):370-76. [PMID: 34463141]

Rodger A. J., Cambiano V., Bruun T., et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet 2019;393(10189):2428-38. [PMID: 31056293]

Rodger A. J., Cambiano V., Bruun T., et al. Sexual activity without condoms and risk of HIV transmission in serodifferent couples when the HIV-positive partner is using suppressive antiretroviral therapy. JAMA 2016;316(2):171-81. [PMID: 27404185]

Sheth P. M., Kovacs C., Kemal K. S., et al. Persistent HIV RNA shedding in semen despite effective antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2009;23(15):2050-54. [PMID: 19710596]

Wood E., Kerr T., Marshall B. D., et al. Longitudinal community plasma HIV-1 RNA concentrations and incidence of HIV-1 among injecting drug users: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2009;338:b1649. [PMID: 19406887]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources | |

| Date of original publication | August 21, 2019 |

| Date of current publication | April 05, 2023 |

| Highlights of changes, additions, and updates in the April 05, 2023 edition |

— |

| Intended users | NYS clinicians |

| Lead author(s) |

Shauna H. Gunaratne, MD, MPH; Jessica Rodrigues, MS |

| Writing group |

Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures. |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

| Related NYSDOH AI resources |

Guidelines

Podcast |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on August 1, 2025