GOALS Framework for Sexual History Taking in Primary Care

Download Printable PDF of GOALS Framework

Date of current publication: September 26, 2023

Lead author: Sarit A. Golub, PhD, MPH, Hunter College and Graduate Center, City University of New York, in collaboration with the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Bureau of HIV

Date of original publication: July 30, 2019

Background: Sexual history taking can be an onerous and awkward task that does not always provide accurate or useful information for patient care. Standard risk assessment questions (e.g., How many partners have you had sex within the last 6 months?; How many times did you have receptive anal sex with a man when he did not use a condom?) may be alienating to patients, discourage honest disclosure, and communicate that the number of partners or acts is the only component of sexual risk and health.

In contrast, the GOALS framework is designed to streamline sexual history conversations and elicit information most useful for identifying an appropriate clinical course of action. The “goal” of the GOALS framework is to reimagine the sexual history to make it easier and more productive for providers and patients.

The GOALS framework was developed in response to 4 key findings from the sexual health research literature:

- Universal HIV/STI screening and biomedical prevention education is more beneficial and cost-effective than risk-based screening [Eckman, et al. 2021; Keenan, et al. 2020; Lancki, et al. 2018; Hull, et al. 2017; Hoots, et al. 2016; Owusu-Edusei, et al. 2016].

- Emphasizing benefits—rather than risks—is more successful in motivating patients toward prevention and care behavior [Reynolds-Tylus 2019; Epton, et al. 2015; Sheeran, et al. 2014; Weinstein and Klein 1995].

- Positive interactions with healthcare providers promote engagement in prevention and care [Howe, et al. 2019; Flickinger, et al. 2013; Alexander, et al. 2012; Bakken, et al. 2000].

- Patients want their healthcare providers to talk with them about sexual health [Agochukwu-Mmonu, et al. 2021; Zhang, et al. 2020; Ryan, et al. 2018; Fairchild, et al. 2016].

Rather than seeing sexual history taking as a means to an end, the GOALS framework considers the sexual history taking process as an intervention that can:

- Increase rates of routine HIV/STI screening;

- Increase rates of universal biomedical prevention and contraceptive education;

- Increase patients’ motivation for and commitment to sexual health behavior; and

- Enhance the patient-care provider relationship, making it a lever for sexual health specifically and overall wellness.

The GOALS framework includes 5 steps:

- Give a preamble that emphasizes sexual health. The healthcare provider briefly introduces the sexual history in a way that de-emphasizes risk, normalizes sexuality as part of routine healthcare, and opens the door for the patient’s questions.

- Offer opt-out HIV/STI testing and information. The healthcare provider tells the patient that they test everyone for HIV and STIs, normalizing both testing and HIV and STI concerns.

- Ask an open-ended question. The healthcare provider starts the sexual history with an open-ended question that helps them identify the aspects of sexual health that are most important to the patient, while allowing them to hear (and then mirror) the language that the patient uses to describe their own body, partner(s), and sexual behaviors.

- Listen for relevant information and fill in the blanks. The healthcare provider asks more pointed questions to elicit information that might be needed for clinical decision-making (e.g., 3-site versus genital-only testing), but these questions are restricted to specific, necessary information. For instance, if a patient has already disclosed that he is a gay man with more than 1 partner, there is no need to ask about the total number of partners or their HIV status to recommend STI/HIV testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) education.

- Suggest a course of action. Consistent with opt-out testing, the healthcare provider offers all patients HIV testing, 3-site STI testing, PrEP education, and contraceptive counseling, unless any of this testing is specifically contraindicated by the sexual history. Rather than focusing on any risk behaviors the patient may be engaging in, this step focuses specifically on the benefits of engaging in prevention behaviors, such as exerting greater control over one’s sex life and sexual health and decreasing anxiety about potential transmission.

Resources for implementation:

- Script, rationale, and goals: Box 1, below, provides a suggested script for each step in the GOALS framework, along with the specific rationale for that step and the goal it is designed to accomplish.

- GOALS Three-Part Video Series (NIH-funded BLUPrInt Project)

- Reimagining the Sexual History, GOALS Approach Evidence and Elements, and Taking Risk Out of the Pitch (AETC): A self-paced, interactive, online training

- The 5Ps model for sexual history-taking (CDC): Note that the GOALS framework is not necessarily designed to replace the 5Ps model (partners, practices, protection from STI, history of STI, prevention of pregnancy); instead, it provides a framework for identifying information related to the 5Ps that improves patient-care provider communication, reduces the likelihood of bias or missed opportunities, and enhances patients’ motivation for prevention and sexual health behavior.

| Box 1: GOALS Framework for the Sexual History |

||

| Component | Suggested Script | Rationale and Goal Accomplished |

| Give a preamble that emphasizes sexual health. | I’d like to talk with you for a couple of minutes about your sexuality and sexual health. I talk to all of my patients about sexual health, because it’s such an important part of overall health. Some of my patients have questions or concerns about their sexual health, so I want to make sure I understand what your questions or concerns might be and provide whatever information or other help you might need. |

|

| Offer opt-out HIV/STI testing and information. | First, I like to test all my patients for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Do you have any concerns about that? |

|

| Ask an open-ended question. | Pick one (or use an open-ended question that you prefer):

|

|

| Listen for relevant information and probe to fill in the blanks. |

|

|

| Suggest a course of action. |

|

|

Download Box 1: GOALS Framework for the Sexual History Printable PDF

References

Agochukwu-Mmonu N, Malani PN, Wittmann D, et al. Interest in sex and conversations about sexual health with health care providers among older U.S. adults. Clin Gerontol 2021;44(3):299-306. [PMID: 33616005]

Alexander JA, Hearld LR, Mittler JN, et al. Patient-physician role relationships and patient activation among individuals with chronic illness. Health Serv Res 2012;47(3 Pt 1):1201-23. [PMID: 22098418]

Bakken S, Holzemer WL, Brown MA, et al. Relationships between perception of engagement with health care provider and demographic characteristics, health status, and adherence to therapeutic regimen in persons with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2000;14(4):189-97. [PMID: 10806637]

Eckman MH, Reed JL, Trent M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sexually transmitted infection screening for adolescents and young adults in the pediatric emergency department. JAMA Pediatr 2021;175(1):81-89. [PMID: 33136149]

Epton T, Harris PR, Kane R, et al. The impact of self-affirmation on health-behavior change: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol 2015;34(3):187-96. [PMID: 25133846]

Fairchild PS, Haefner JK, Berger MB. Talk about sex: sexual history-taking preferences among urogynecology patients and general gynecology controls. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg 2016;22(5):297-302. [PMID: 27171322]

Flickinger TE, Saha S, Moore RD, et al. Higher quality communication and relationships are associated with improved patient engagement in HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63(3):362-66. [PMID: 23591637]

Hoots BE, Finlayson T, Nerlander L, et al. Willingness to take, use of, and indications for pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men-20 US cities, 2014. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63(5):672-77. [PMID: 27282710]

Howe LC, Leibowitz KA, Crum AJ. When your doctor “gets it” and “gets you”: the critical role of competence and warmth in the patient-provider interaction. Front Psychiatry 2019;10:475. [PMID: 31333518]

Hull S, Kelley S, Clarke JL. Sexually transmitted infections: compelling case for an improved screening strategy. Popul Health Manag 2017;20(S1):s1-11. [PMID: 28920768]

Keenan M, Thomas P, Cotler K. Increasing sexually transmitted infection detection through screening at extragenital sites. J Nurs Pract 2020;16(2):e27-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2019.07.023

Lancki N, Almirol E, Alon L, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis guidelines have low sensitivity for identifying seroconverters in a sample of young Black MSM in Chicago. AIDS 2018;32(3):383-92. [PMID: 29194116]

Owusu-Edusei K, Jr., Hoover KW, Gift TL. Cost-effectiveness of opt-out chlamydia testing for high-risk young women in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2016;51(2):216-24. [PMID: 26952078]

Reynolds-Tylus T. Psychological reactance and persuasive health communication: a review of the literature. Frontiers in Communication 2019;4. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2019.00056

Ryan KL, Arbuckle-Bernstein V, Smith G, et al. Let’s talk about sex: a survey of patients’ preferences when addressing sexual health concerns in a family medicine residency program office. PRiMER 2018;2:23. [PMID: 32818195]

Sheeran P, Harris PR, Epton T. Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychol Bull 2014;140(2):511-43. [PMID: 23731175]

Weinstein ND, Klein WM. Resistance of personal risk perceptions to debiasing interventions. Health Psychol 1995;14(2):132-40. [PMID: 7789348]

Zhang X, Sherman L, Foster M. Patients’ and providers’ perspectives on sexual health discussion in the United States: a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns 2020;103(11):2205-13. [PMID: 32601041]

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

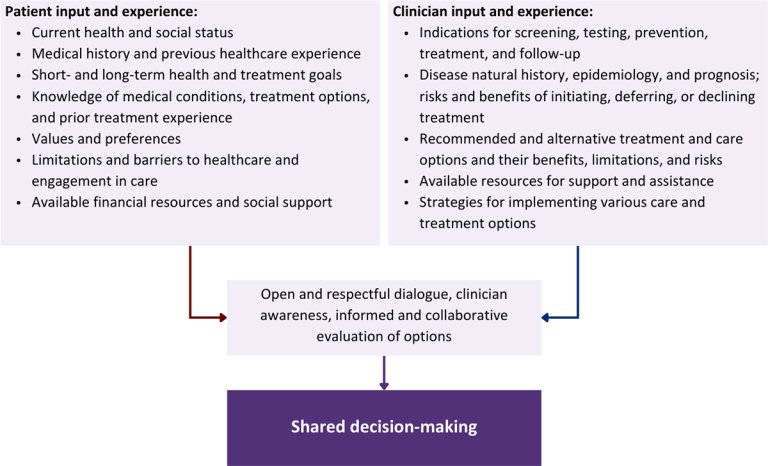

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources | |

| Date of original publication | July 30, 2019 |

| Date of current publication | September 26, 2023 |

| Highlights of changes, additions, and updates in the September 26, 2023 edition |

— |

| Intended users | NYS clinicians |

| Lead author |

Sarit A. Golub, PhD, MPH, Hunter College and Graduate Center, City University of New York, in collaboration with the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, Bureau of HIV |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures. |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on July 14, 2025