Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: October 15, 2024

Lead authors: Daniela E. DiMarco, MD, MPH; Marguerite A. Urban, MD

Writing group: Rona M. Vail, MD, AAHIVS; Sanjiv S. Shah, MD, MPH, AAHIVM, AAHIVS; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA, AAHIVS; Samuel T. Merrick, MD, FIDSA; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD, FACP, AAHIVS; Jessica Rodrigues, MPH, MS; Brianna L. Norton, DO, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH, MSc, FACP

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: September 25, 2023

This guideline on the use of doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP) for prevention of bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea, was developed by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) Clinical Guidelines Program to support clinicians caring for adults and adolescents with and without HIV who are at risk of acquiring STIs. The goals of this guideline are to:

- Summarize the available evidence regarding the use of doxy-PEP for preventing syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea infections

- Provide evidence-based clinical recommendations for the use of doxy-PEP

- Present practical considerations for prescribing doxy-PEP

The literature on this topic is evolving rapidly, with several clinical trials ongoing. To prepare this guideline, the authors conducted a review of the published literature through MEDLINE, conference presentations, and existing published guidance within the United States and internationally.

Biomedical Prevention of STIs

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Biomedical Prevention of STIs

|

Abbreviations: doxy-PEP, doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection. |

The United States, including New York State, continues to see high rates of reportable STIs, specifically syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea CDC(b) 2024, despite decades of public health efforts and prevention strategies aimed at curbing the STI epidemic. Some populations, including men who have sex with men (MSM), young people, and some racial and ethnic minority groups, are disproportionately affected by STIs CDC(b) 2024. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) STI surveillance data from 2022 note that reportable STIs continue to disproportionately affect people who identify as Black/African American and American Indian/Alaska Native CDC(b) 2024, making clear that established STI prevention strategies are insufficient.

Biomedical methods for HIV prevention with HIV PrEP and PEP have been very effective. Researchers identified doxycycline as a candidate for biomedical prevention of STIs. In 2011, Wilson and colleagues used mathematical modeling based on sexual behavior factors to predict doxy-PEP efficacy among MSM in Australia. Assuming 50% uptake and 70% efficacy, the model predicted a 50% reduction in syphilis cases after 1 year and an 85% reduction after 10 years Wilson, et al. 2011. Doxycycline is an antibiotic in the tetracycline class and is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the management of many different types of infections Lexicomp 2023; FDA 2016. Doxycycline is available in 2 different formulations: hyclate, which is more water soluble, and monohydrate, which is less water soluble so may have fewer gastrointestinal adverse effects. Common uses include treatment of chlamydia, syphilis, respiratory infections, and skin and soft tissue infections. Doxycycline has also been used as both a PrEP and PEP agent for certain bacterial and parasitic infections, including Lyme disease, leptospirosis, and malaria Grant, et al. 2020.

When used in nonpregnant adults, doxycycline is safe and well tolerated, has excellent oral bioavailability, is low cost, and is widely available. Adverse effects of doxycycline are generally mild, with gastrointestinal symptoms being the most common. Other adverse effects include photosensitivity and esophageal injury. Doxycycline is contraindicated in pregnancy because of potential adverse effects on the fetus Lexicomp 2023. Doxycycline is also used safely for prolonged periods for some conditions, including acne Zaenglein, et al. 2016 and prosthetic joint infections Osmon, et al. 2013. A systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the safety of long-term (8 weeks or more) doxycycline use for treatment or prevention of a variety of conditions, identifying 67 studies for analysis over a 20-year period ending in January 2023 Chan, et al. 2023. Nearly one-third of the studies reported mild to moderate adverse effects, most frequently gastrointestinal and dermatologic. Severe adverse effects were uncommon. These factors make doxycycline a promising prophylactic agent; however, the effects on antimicrobial resistance and the microbiome with widespread use are still under investigation.

Doxycycline as PEP

Available evidence on doxy-PEP to prevent bacterial STIs is limited but increasing. Current data are from randomized clinical trials, observational studies, modeling studies, and surveys on acceptability for use. Studies predominantly included cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men, were receiving HIV PrEP or in care for HIV infection, were aged 35 years and older, and were White.

In 4 randomized clinical trials comparing doxy-PEP with standard of care (routine STI testing), participants received HIV PrEP or HIV care, and in 3 of the 4 trials participants had a history of ≥1 bacterial STI in the prior year. The study protocols used oral doxycycline 200 mg taken ideally within 24 hours or up to 72 hours of condomless sex to prevent bacterial STIs. All participants were tested for STIs every 3 months during the study period Molina, et al. 2024; Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023; Stewart, et al. 2023; Molina, et al. 2018. In the 3 trials conducted among cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men, there were significant reductions in chlamydia and syphilis, but results were mixed regarding the efficacy of doxy-PEP in preventing gonococcal infections, likely at least in part because of geographic variability in prevalence of tetracycline resistance in gonococci Molina, et al. 2024; Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023; Fairley and Chow 2018; Molina, et al. 2018; Siguier and Molina 2018. In a study that included only cisgender women taking HIV PrEP, doxy-PEP was not effective at preventing bacterial STIs Stewart, et al. 2023.

A modeling study analyzed data from an LGBTQ-focused health center in the United States to assess the effect of doxy-PEP use on STI incidence among more than 10,000 individuals assigned male sex at birth (including cisgender men, transgender women, and nonbinary individuals) who had male sex partners and STI testing (chlamydia, gonorrhea, or syphilis) on record Traeger, et al. 2023. STI incidence was 35.9 per 100 person-years. Modeling demonstrated that, rather than prescribing doxy-PEP based solely on HIV or PrEP engagement, prescribing based on STI history resulted in an efficient strategy that balanced uptake and preventive impact. An approach combining these factors, as was done in the clinical trials, was not modeled in this projection. Seven different strategies for prescribing doxy-PEP over 12 months were modeled Traeger, et al. 2023. Prescribing to all in the sample, an estimated 71% of gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis cases could have been averted (number needed to treat [NNT] for 1 year to avert 1 STI diagnosis of 3.9). Prescribing to individuals with HIV (12%) or who were taking HIV PrEP (52%) could have averted 60% of STI diagnoses in this group (NNT of 2.9). Limiting prescribing to individuals with an STI diagnosis, the proportion using doxy-PEP was reduced to 38% and would have averted 39% of STI diagnoses (NNT of 2.4).

This committee’s recommendations on provision of doxy-PEP are outlined above, and implementation considerations are discussed in the guideline section Practical Considerations for Doxy-PEP Implementation. The risk-benefit profile for doxy-PEP is expected to vary based on individual patient factors and community and sexual network STI prevalence. Factors associated with increased likelihood of STI exposure include having multiple sex partners, engaging in group sex, engaging in transactional sex, and combining sex and substance use Workowski, et al. 2021. An individualized assessment is an important aspect of shared decision-making between patient and clinician.

The A-level recommendations for doxy-PEP use among cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men are based on the significant reductions in bacterial STIs reported in the 3 clinical trials Molina, et al. 2024; Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023; Molina, et al. 2018, described in detail below, and post-implementation observational data Sankaran, et al. 2024; Scott, et al. 2024. Although the majority of STIs among these populations are asymptomatic and without complications, the significant decrease in STI occurrence provides potential benefits to individuals and the broader community and likely outweighs the potential harms of doxycycline use. Based on the lack of efficacy reported for doxy-PEP in cisgender women in Kenya Stewart, et al. 2023 , there is insufficient evidence to recommend its use in individuals at risk of STIs through receptive vaginal sex. However, hair samples examining doxycycline levels point to possible adherence issues Stewart, et al. 2023, and pharmacologic data from an unrelated study suggest adequate tissue and secretion levels for protection Haaland, et al. 2023.

There are no published data evaluating doxy-PEP use among cisgender men with sex partners assigned female sex at birth. However, doxy-PEP use among cisgender men (with female sex partners) who have similar STI risk factors as the doxy-PEP study populations (i.e., history of STIs, multiple sex partners, high-prevalence populations) could also potentially provide individual and community benefits outweighing the risks of doxycycline use. The NNT and degree of potential protective effect with insertive vaginal sex are unknown. This strategy has the possibility of indirectly extending the potential benefits of doxy-PEP use to cisgender women (who have sex with men) and to neonates, who experience the majority of complications of bacterial STIs, through reduction of community rates and may be considered by clinicians on a case-by-case basis. Doxy-PEP has not been studied in adolescents younger than 18 years, and adherence and efficacy in this group are unknown.

Evidence from the IPERGAY trial: The first published evidence on doxy-PEP was derived from a substudy of the ANRS IPERGAY randomized trial of on-demand HIV PrEP among cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men in France. The substudy demonstrated an approximately 70% reduction in incident chlamydia and syphilis infections but no significant reduction in gonorrhea infections in a population reporting sex practices placing them at high risk of STIs Molina, et al. 2018. In this open-label extension, more than 200 participants (cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men) taking HIV PrEP were randomized to receive doxycycline hyclate 200 mg as a single dose within 24 to 72 hours after condomless sex or no doxy-PEP. Study participants were mostly White, aged 30 years and older, and reported having multiple sex partners (10 in 2 months) and engaging in condomless sex acts (10 in 4 weeks). Participants were instructed not to exceed 3 doses per week; the median number of doxy-PEP doses used per month was 3.4, which was fewer than the number of reported condomless sexual encounters. Of participants, 83% took doxy-PEP within 24 hours of sex. Gastrointestinal adverse effects were reported by more than half of the participants, resulting in 8 discontinuations. Doxy-PEP was associated with significant reductions in the incidence of first STI and, in individual analyses, of incident chlamydia and syphilis infections. For incident gonorrhea, however, there was no significant reduction in the doxy-PEP group, which was attributed to the high prevalence of tetracycline resistance among gonococcal isolates in France.

Evidence from the DoxyPEP trial: The open-label randomized DoxyPEP study analyzed data from 501 adult cisgender MSM (96%) and transgender women who have sex with men (4%) who were either taking HIV PrEP (n = 360) or had HIV (n = 194) and who had a bacterial STI and reported condomless sex with a male partner within the past year. Participants were randomized to receive either doxy-PEP as 200 mg of delayed-release doxycycline hyclate (ideally within 24 hours but no later than 72 hours after condomless sex) or standard of care Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023. STI testing was performed every 3 months over 1 year of follow-up. Participants had a high prevalence of baseline bacterial STIs and a median of 9 sex partners in the 3 months before enrollment, and 59% reported substance use. The median participant age was 38 years, and 67% were White, 7% were Black, 11% were Asian or Pacific Islander, 15% were multiracial or other, and 30% were Hispanic or Latino. The maximum dose of doxycycline was 200 mg within a 24-hour period, and the medication was dispensed at 3-month intervals. The initial doxycycline supply included enough tablets for daily use, and the amount dispensed each quarter was adjusted in follow-up based on frequency of sex and doses used.

The DoxyPEP study was stopped early after interim analysis noted a significant protective effect in the intervention arm, and participants in the standard-of-care group were offered doxy-PEP Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023. Modified intention-to-treat analysis included participants who completed a median of 9 months of follow-up. Gonorrhea was the most common STI diagnosed, and there were very few cases of early syphilis. Median doxy-PEP use was 4 doses per month, with 25% of participants reporting more than 10 doses per month. This study demonstrated a 52% quarterly reduction in any incident STI among participants with HIV (hazard ratio [HR], 0.48; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.28-0.83), and a 66% reduction among those taking HIV PrEP (HR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.23-0.51) Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023; Luetkemeyer, et al. 2022; SFDPH 2024. Among participants taking HIV PrEP, the relative risk (RR) of any incident STI was 0.34 (95% CI, 0.24-0.46; P<.001), and the NNT was 4.7, whereas among participants with HIV, the RR for any incident STI was 0.38 (95% CI, 0.24-0.60; P<.001), and the NNT was 5.3 Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023.

In subgroup analyses, among participants taking HIV PrEP, the significant risk reduction was maintained for each STI individually, including infections at extragenital sites, except for pharyngeal chlamydia Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023. Among participants with HIV, doxy-PEP did not significantly reduce incident early syphilis or urethral or pharyngeal chlamydia or gonorrhea. Doxycycline was well tolerated, and self-reported adherence was high. Antimicrobial resistance was also evaluated in this study and is discussed below (see guideline section Antimicrobial Resistance, below).

Evidence from the DOXYVAC trial: In the phase III randomized 2×2 factorial designed DOXYVAC trial, the efficacy of both doxy-PEP for bacterial STI prophylaxis and meningococcal serotype B vaccination for preventing gonococcal infection was investigated among 446 cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men taking HIV PrEP in France Molina, et al. 2024. Participants were predominantly White, had a median age of 40 years, were long-term HIV PrEP users, reported multiple sex partners, and had multiple prior STIs. Unblinded early interim analysis revealed significant reductions in any incident STI, and participants were all offered doxy-PEP. Doxy-PEP significantly reduced the incidence of the first episode of chlamydia (adjusted HR [aHR], 0.14; 95% CI, 0.09-0.23; P<.0001), syphilis (aHR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.11-0.41; P<.0001), and gonorrhea (aHR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.52-0.87; P=.0025) infections. Self-reported adherence was high in this study at more than 70% (detectable concentrations in plasma and urine were more than 60% in the doxy-PEP group at 6 months), with a median use of 3 doses per month and a median time to doxy-PEP intake after sex of 15 hours. Additionally, antimicrobial resistance was analyzed and is discussed below (see guideline section Antimicrobial Resistance, below).

Doxy-PEP and receptive vaginal sex: Data from a randomized trial in Kisumu, Kenya, that compared doxy-PEP with the standard of care among cisgender women aged 18 to 30 years taking HIV PrEP found that doxy-PEP was not effective for bacterial STI prevention in this population Stewart, et al. 2023. The study enrolled 449 participants from 2020 to 2022, with very little loss to follow-up. At baseline, 18% of participants were diagnosed with an STI (14% with chlamydia, 4% with gonorrhea, and <1% with syphilis). Adherence by self-report demonstrated at least 80% of condomless sex encounters were covered, with almost all doses taken within 24 hours of condomless sex. Incident STIs were similar between groups (annual incidence of 27%), with no significant reduction in the doxy-PEP group. No incident HIV infections were reported. Fifty participants (22%) in the doxy-PEP group were randomly selected for hair sampling to assess doxycycline concentrations using an assay developed by study investigators; in this subgroup, doxycycline was detected in the hair of 56% of participants on at least 1 visit and in 32.6% on all visits for which hair specimens were collected (58/178 total visits) Stewart, et al. 2023. The investigators reported that a study to validate the assay with intermittent dosing of doxycycline is in development Kojima and Klausner 2024.

The reason for the lack of demonstrable efficacy of doxy-PEP in this study is unclear. Possible factors influencing these results include the prevalence of high-level tetracycline resistance among gonococcal isolates in Kenya Soge, et al. 2023, adherence being less than what was ascertained by self-report, and biologic or anatomic differences. An unrelated study in the United States evaluated drug concentrations with event-driven oral dosing and showed that 200 mg of doxycycline hyclate achieved concentrations above minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) for syphilis, chlamydia, and gonorrhea in rectal, vaginal, and cervical tissues as well as rectal and vaginal secretions; these concentrations were sustained at least 2 days after dosing, although the degree above MIC was much lower for Neisseria gonorrhoeae Haaland, et al. 2023. Higher doxycycline concentrations were sustained for a longer duration in rectal secretions than in vaginal secretions, although the levels remained above the MIC.

Additional studies on doxy-PEP to prevent STIs through receptive vaginal sex are in development.

Doxy-PEP post-implementation: In a large sexual health clinic setting in San Francisco, California, following the release of the DoxyPEP trial results, all individuals on HIV PrEP were offered doxy-PEP (approximately 3,000 patients). At 9-month follow-up there was approximately 39% uptake of doxy-PEP Scott, et al. 2024. Baseline incidence rates for any STI (gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis) were approximately 3 times higher in the doxy-PEP group than in the group not on doxy-PEP. By the last quarter of the study period, STI incidence rates in the doxy-PEP group were significantly reduced and comparable to those in the no-doxy-PEP group, although the reduction was not significant for the individual outcome of gonorrhea Scott, et al. 2024. These results demonstrate not only the effect of doxy-PEP on preventing STIs but also the STI risk stratification of individuals by self-selection of who accepted or declined doxy-PEP.

The same investigators tracked quarterly numbers of new patients starting doxy-PEP and examined the effect of doxy-PEP with early implementation on local STI epidemiology Sankaran, et al. 2024. It was concluded that early release of guidance and implementation for doxy-PEP at high-volume clinics was associated with substantial reductions in reported cases of chlamydia and early syphilis for just over 1 year among cisgender men and transgender women with sex partners assigned male sex at birth (an approximately 50% drop for each); notably, there was no community impact on gonococcal infections Sankaran, et al. 2024. The investigators noted that other factors, including changes in sex practices and activities in response to mpox, might have affected the results, although the results were sustained into 2023 Sankaran, et al. 2024.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Antimicrobial Resistance

Published research, previous guideline statements, and editorials have raised concerns about the impact of doxy-PEP on the emergence of antimicrobial resistance for bacterial STIs and other non-STI pathogens with widespread long-term use Molina, et al. 2024; Cornelisse, et al. 2023; Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023; Kohli, et al. 2022; Lewis 2022; Luetkemeyer, et al. 2022; Grant, et al. 2020; Molina, et al. 2018; Siguier and Molina 2018; Golden and Handsfield 2015. Increasing antimicrobial resistance is a concern at both the individual and population levels Cornelisse, et al. 2023. It may take years to determine this effect, and additional research is needed Siguier and Molina 2018. To date, studies of doxy-PEP have not found detectable resistance in Treponema pallidum or Chlamydia trachomatis strains Cornelisse, et al. 2023. Doxycycline resistance is already a concern for other bacterial STIs, including M. genitalium and N. gonorrhoeae, and there are few alternative therapeutic options for M. genitalium Workowski, et al. 2021. Tetracycline (used as a surrogate for doxycycline) resistance in N. gonorrhoeae isolates varies geographically and is reported at 20.1% nationwide by the CDC Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project CDC(b) 2024.

Doxycycline is an important antibiotic used to treat non-sexually transmitted infections when other oral treatment options are severely limited, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Doxycycline also remains an option for antimicrobial-resistant gonococcal infections if susceptibility is confirmed. The benefits of widespread use of doxycycline must be weighed against the known and potential risks of selecting for antimicrobial resistance and altering the various microbiomes (e.g., gastrointestinal, vaginal, skin). In an analysis of more than 2,000 gonococcal isolates in Europe, the presence of 2 common tetracycline-associated mutations was strongly associated with additional mutations conferring cross-resistance to other antibiotics, including beta-lactams, macrolides, and fluoroquinolones Vanbaelen, et al. 2023. This raises concern that selecting for gonorrhea tetracycline resistance may also impact the effectiveness of other antibiotic classes, including cephalosporins, which are the standard of care for gonorrhea treatment.

To assess the impact of doxy-PEP use on antimicrobial resistance, nares and oropharynx specimens were examined for S. aureus in the DoxyPEP study Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023, and tetracycline resistance in extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) Escherichia coli (as a marker of microbiome influence) and MRSA were assessed in the DOXYVAC study Molina, et al. 2024. In the DoxyPEP study, cultures were available for 17.2% of gonorrhea infections (n = 44) Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023. Of these, baseline tetracycline resistance (a surrogate for doxycycline resistance) was 27%. After enrollment, resistance was 38% in the doxycycline groups and 12% in the standard-of-care groups, and doxy-PEP appeared less protective for tetracycline-resistant gonorrhea, although the sample size was small Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023; Luetkemeyer, et al. 2022. S. aureus was cultured from the oronasopharynx in 45% of participants, and baseline doxycycline resistance was 12% Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023. At 1 year, S. aureus colonization identified by culture was significantly less in the doxy-PEP groups than the standard-of-care groups, and prevalence of doxycycline-resistant isolates was 16% in the doxycycline groups and 8% in the standard-of-care groups Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023.

In the DOXYVAC study, baseline tetracycline resistance was found in all 78 specimens for which gonorrhea cultures were available, and the prevalence of high-level resistance was greater in the doxy-PEP group (36%) than in the standard-of-care group (13%); no C. trachomatis resistance was detected by culture or sequencing Molina, et al. 2024. As markers for assessing the impact of doxy-PEP on the microbiome, there was no significant difference between the groups in detection of ESBL E. coli from anal swabs or MRSA from the pharynx.

Based on these data, the efficacy of doxy-PEP for gonorrhea is expected to differ depending on the prevalence of tetracycline resistance in a given population or geographic region. For S. aureus, doxy-PEP is associated with increased resistance Luetkemeyer, et al. 2023, which is an important consideration in the preservation of antimicrobial treatment options for MRSA infection.

Recommendations Outside of New York State

Several organizations have issued guidance regarding the use of doxy-PEP Bachmann, et al. 2024; Cornelisse, et al. 2024; Werner, et al. 2024; CDPH 2023; Gandhi, et al. 2023; NCSD 2023; PHSKC 2023; SCPHD 2023; Kohli, et al. 2022; SFDPH 2024. There is variability regarding implementation of this intervention, although dosing recommendations and the guidance to bundle doxy-PEP with comprehensive sexual health services have been uniformly consistent with studies to date.

The British Association for Sexual Health and HIV and the UK Health Security Agency do not endorse the use of doxycycline as prophylaxis, primarily because of concerns regarding antimicrobial resistance and limited long-term data Kohli, et al. 2022. The Australian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis, and Sexual Health Medicine recommends use of doxy-PEP primarily for the prevention of syphilis among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men Cornelisse, et al. 2024. Disagreements noted are centered around the risks and benefits at the individual and population levels, including the potential for selection of antimicrobial resistance and impact on the microbiome Cornelisse, et al. 2024; Kohli, et al. 2022. The German STI Society released a position statement recommending against broad implementation of doxy-PEP (without further data regarding antimicrobial resistance), although they cited situations in which doxy-PEP use may be considered on a case-by-case basis Werner, et al. 2024.

The San Francisco Department of Public Health (SFDPH) released the first set of guidelines on doxy-PEP use, recommending doxy-PEP for cisgender men and transgender women who meet 2 eligibility criteria outlined in the DoxyPEP study: 1) have a diagnosis of a bacterial STI within the last year, and 2) report condomless sex with at least 1 male partner in the past year SFDPH 2024. The SFDPH also recommends offering doxy-PEP via shared decision-making to cisgender men, transgender men, and transgender women who have had multiple sex partners assigned male sex at birth within the past year, even in the absence of a prior STI diagnosis. The SFDPH dosing and prescribing recommendations are the same as those used in the DoxyPEP study; however, the SFDPH notes that immediate- or extended-release doxycycline could be used, although the extended-release formulation may be more expensive. The California Department of Health (CDPH) sent out a Dear Colleague Letter on April 28, 2023, with recommendations on doxy-PEP CDPH 2023. The CDPH recommends doxy-PEP for cisgender men or transgender women with 1 or more bacterial STI in the past 12 months and suggests offering doxy-PEP via shared decision-making to all nonpregnant individuals at increased risk of STI acquisition, even if there is no history of an STI diagnosis. To date, there are 3 states in total with guidance on provision of doxy-PEP to any individual at risk for STIs: California CDPH 2023, Minnesota MDH 2024, and New Mexico NMDPH 2023.

Public Health–Seattle and King County (PHSKC) recommends that clinicians engage in shared decision-making on doxy-PEP with cisgender men and transgender women with history of an STI in the past year and ongoing sex encounters with partners assigned male sex at birth PHSKC 2023. The PHSKC guidance also recommends stronger consideration for individuals in this population with a specific history of syphilis or multiple STIs in the prior year and that clinicians consider prescribing doxy-PEP episodically when patients anticipate their STI exposure risk to be elevated (e.g., group sex events).

In 2024, the CDC released formal guidelines on the use of doxy-PEP Bachmann, et al. 2024. For cisgender men and transgender women who have had a bacterial STI in the past year and have sex partners assigned male sex at birth, the CDC recommends providing counseling about doxy-PEP and offering this prevention strategy via shared-decision making. Comprehensive sexual health services, including STI prevention counseling, STI screening, immunizations, and linkage to HIV prevention and treatment, are also recommended.

The National Coalition of STD Directors released a doxy-PEP implementation toolkit with basic guidance on community engagement, workflow, education, program evaluation, and prescribing logistics NCSD 2023. Highlights from the toolkit emphasize ensuring equitable criteria for offering doxy-PEP and reducing unnecessary access restrictions.

Practical Considerations for Doxy-PEP Implementation

As with any drug therapy, a review of the patient’s health history, current medications, and allergies to ensure there are no health concerns, drug-drug interactions, or medication allergies that would preclude use is indicated before initiating doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP). Concurrent use of doxy-PEP with daily doxycycline or tetracycline for other conditions is contraindicated. Medications other than doxycycline have not been studied for bacterial sexually transmitted infection (STI) PEP. When doxycycline is not tolerated or contraindications to its use exist, doxy-PEP is not recommended. Practical considerations for prescribing and monitoring doxy-PEP are outlined in Table 1, below.

| Abbreviations: ARV, antiretroviral medication; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CBC, complete blood count; doxy-PEP, doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis; GI, gastrointestinal; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection.

Note:

|

|

| Table 1: Considerations for Doxy-PEP Implementation | |

| Consideration(s) | Comments |

| Available formulations |

|

| Administration |

|

| Contraindications, drug-drug interactions, and dose adjustments |

|

| Adverse effects |

|

| Supply of doxy-PEP medications |

|

| Follow-up and laboratory monitoring |

|

| Key points for patient education |

|

Download Table 1: Considerations for Doxy-PEP Implementation Printable PDF

Managing STI Exposures in Patients Taking Doxy-PEP

Because doxy-PEP is not 100% effective at preventing STIs, it is important for patients using doxy-PEP who have sex partners diagnosed with bacterial STIs to undergo STI testing. Syphilis exposures are considered separately from chlamydia and gonorrhea exposures.

Patients taking doxy-PEP who are exposed to early syphilis within the prior 90 days can be treated presumptively per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) STI Treatment Guidelines Workowski, et al. 2021 regardless of test results. If treatment is declined, repeat syphilis testing at 3 months is recommended because of the potential for an extended period of syphilis incubation. If the syphilis exposure was more than 90 days prior, management is based on test results.

Patients taking doxy-PEP who are exposed to chlamydia or gonorrhea can be treated based on test results. Alternatively, these individuals can be treated empirically per the CDC STI Treatment Guidelines as if they were not using doxy-PEP.

Managing Diagnosed STIs in Patients Taking Doxy-PEP

Treat incident STIs according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) STI Treatment Guidelines Workowski, et al. 2021.

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS: DOXYCYCLINE POST-EXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS TO PREVENT BACTERIAL SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED INFECTIONS |

Biomedical Prevention of STIs

|

Abbreviations: doxy-PEP, doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection. |

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

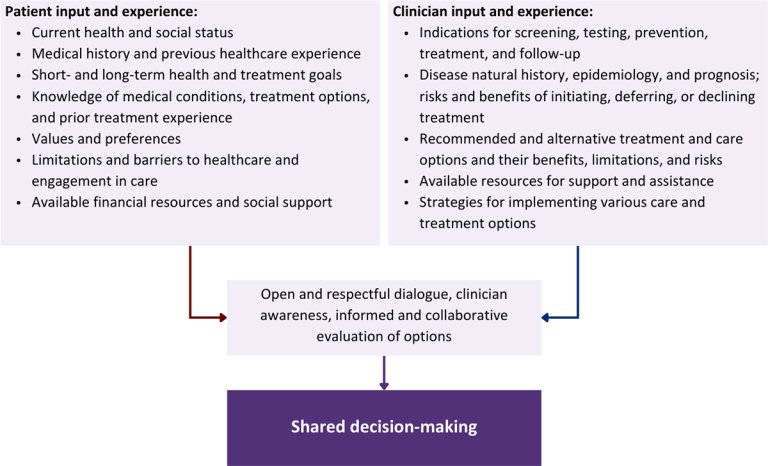

Rationale

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Bachmann L. H., Barbee L. A., Chan P., et al. CDC clinical guidelines on the use of doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis for bacterial sexually transmitted infection prevention, United States, 2024. MMWR Recomm Rep 2024;73(2):1-8. [PMID: 38833414]

CDC(a). Doxy PEP for bacterial STI prevention. 2024 Aug 14. https://www.cdc.gov/sti/hcp/doxy-pep/index.html [accessed 2024 Oct 7]

CDC(b). Sexually transmitted infections surveillance 2022. 2024 Jan 30. https://www.cdc.gov/std/statistics/2022/default.htm [accessed 2024 Aug 19]

CDPH. Doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP) for the prevention of bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs). 2023 Apr 28. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document%20Library/CDPH-Doxy-PEP-Recommendations-for-Prevention-of-STIs.pdf [accessed 2024 Aug 19]

Chan P. A., Le Brazidec D. L., Becasen J. S., et al. Safety of longer-term doxycycline use: a systematic review and meta-analysis with implications for bacterial sexually transmitted infection chemoprophylaxis. Sex Transm Dis 2023;50(11):701-12. [PMID: 37732844]

Cornelisse V. J., Ong J. J., Ryder N., et al. Interim position statement on doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP) for the prevention of bacterial sexually transmissible infections in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand - the Australasian Society for HIV, Viral Hepatitis and Sexual Health Medicine (ASHM). Sex Health 2023;20(2):99-104. [PMID: 36927481]

Cornelisse V. J., Riley B., Medland N. A. Australian consensus statement on doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP) for the prevention of syphilis, chlamydia and gonorrhoea among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. Med J Aust 2024;220(7):381-86. [PMID: 38479437]

Fairley C. K., Chow E. P. Doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis: let the debate begin. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18(3):233-34. [PMID: 29229439]

FDA. Doxycycline hyclate delayed-release tablets, for oral use. 2016 Apr. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/90431Orig1s010lbl.pdf [accessed 2024 Aug 19]

Gandhi R. T., Bedimo R., Hoy J. F., et al. Antiretroviral drugs for treatment and prevention of HIV infection in adults: 2022 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA 2023;329(1):63-84. [PMID: 36454551]

Golden M. R., Handsfield H. H. Preexposure prophylaxis to prevent bacterial sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis 2015;42(2):104-6. [PMID: 25585070]

Grant J. S., Stafylis C., Celum C., et al. Doxycycline prophylaxis for bacterial sexually transmitted infections. Clin Infect Dis 2020;70(6):1247-53. [PMID: 31504345]

Haaland R., Fountain J., Dinh C., et al. Mucosal pharmacology of doxycycline for bacterial STI prevention in men and women. Abstract 118. CROI; 2023 Feb 19-22; Seattle, WA. https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/mucosal-pharmacology-of-doxycycline-for-bacterial-sti-prevention-in-men-and-women/

Kohli M., Medland N., Fifer H., et al. BASHH updated position statement on doxycycline as prophylaxis for sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Infect 2022;98(3):235-36. [PMID: 35414633]

Kojima N., Klausner J. D. Doxycycline to prevent sexually transmitted infections in women. N Engl J Med 2024;390(13):1248-49. [PMID: 38598593]

Lewis D. Push to use antibiotics to prevent sexually transmitted infections raises concerns. Nature 2022;612(7938):20-21. [PMID: 36418876]

Lexicomp. Doxycycline (Lexi-Drugs). 2023 Sep 16. https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/patch_f/6792?searchUrl=%2Flco%2Faction%2Fsearch%3Forigin%3Dapi%26t%3Dglobalid%26q%3D6077%26nq%3Dtrue [accessed 2024 Aug 19]

Luetkemeyer A. F., Dombrowski J. C., Cohen S., et al. Doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis for STI prevention among MSM and transgender women on HIV PrEP or living with HIV: high efficacy to reduce incident STIs in a randomized trial. AIDS; 2022 Jul 29-Aug 2; Montreal, Canada. https://programme.aids2022.org/Abstract/Abstract/?abstractid=13231

Luetkemeyer A. F., Donnell D., Dombrowski J. C., et al. Postexposure doxycycline to prevent bacterial sexually transmitted infections. N Engl J Med 2023;388(14):1296-1306. [PMID: 37018493]

MDH. Interim recommendations for the use of doxycycline for post-exposure prophylaxis (doxy PEP) for the prevention of certain bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs). 2024 Mar 15. https://www.health.state.mn.us/diseases/stds/hcp/doxypep.pdf [accessed 2024 Aug 30]

Molina J. M., Bercot B., Assoumou L., et al. Doxycycline prophylaxis and meningococcal group B vaccine to prevent bacterial sexually transmitted infections in France (ANRS 174 DOXYVAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial with a 2 x 2 factorial design. Lancet Infect Dis 2024;24(10):1093-1104. [PMID: 38797183]

Molina J. M., Charreau I., Chidiac C., et al. Post-exposure prophylaxis with doxycycline to prevent sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men: an open-label randomised substudy of the ANRS IPERGAY trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2018;18(3):308-17. [PMID: 29229440]

NCSD. Doxycycline for STI PEP implementation toolkit. 2023 Jul. https://www.ncsddc.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Doxycycline-as-STI-PEP-Toolkit-July-2023.pdf [accessed 2024 Aug 19]

NMDPH. New Mexico Health Alert Network (HAN): doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP) for the prevention of bacterial sexually transmitted infections. 2023 Aug 23. https://www.nmhealth.org/publication/view/general/8411/ [accessed 2024 Aug 30]

Osmon D. R., Berbari E. F., Berendt A. R., et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56(1):e1-25. [PMID: 23223583]

PHSKC. Doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (doxy-PEP) to prevent bacterial STIs in men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender persons who have sex with men. 2023 Mar 20. https://kingcounty.gov/depts/health/communicable-diseases/~/media/depts/health/communicable-diseases/documents/hivstd/DoxyPEP-Guidelines.ashx [accessed 2024 Aug 19]

Sankaran M., Glidden D. V., Kohn R. P., et al. Doxy-PEP associated with declines in chlamydia and syphilis in MSM and trans women in San Francisco. Abstract 127. CROI; 2024 Mar 3-6; Denver, CO. https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/doxy-pep-associated-with-declines-in-chlamydia-and-syphilis-in-msm-and-trans-women-in-san-francisco/

Scott H., Roman J., Spinelli M. A., et al. Doxycycline PEP: high uptake and significant decline in STIs after clinical implementation. Abstract 126. CROI; 2024 Mar 3-6; Denver, CO. https://www.croiconference.org/abstract/doxycycline-pep-high-uptake-and-significant-decline-in-stis-after-clinical-implementation/

SCPHD. Doxycycline use as post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent bacterial sexually transmitted infections. 2023 Mar 20. https://files.santaclaracounty.gov/migrated/doxypep_guidance.pdf?VersionId=8pm4enzN0hwl_sbAHbFMESKrMVJOvedf [accessed 2024 Aug 19]

SFDPH. Health update: updated recommendations for prescribing doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis (doxyPEP). 2024 Sep 12. https://www.sf.gov/sites/default/files/2024-09/Update-Updated-Recommendations-Prescribing-Doxy-PEP-SFDPH-FINAL-9.12.24.pdf [accessed 2024 Oct 15]

Siguier M., Molina J. M. Doxycycline prophylaxis for bacterial sexually transmitted infections: promises and perils. ACS Infect Dis 2018;4(5):660-63. [PMID: 29570279]

Soge O. O., Issema R., Bukusi E., et al. Predominance of high-level tetracycline-resistant Neisseria gonorrhoeae in Kenya: implications for global implementation of doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis for prevention of sexually transmitted infections. Sex Transm Dis 2023;50(5):317-19. [PMID: 36728331]

Stewart J., Oware K., Donnell D., et al. Doxycycline prophylaxis to prevent sexually transmitted infections in women. N Engl J Med 2023;389(25):2331-40. [PMID: 38118022]

Traeger M. W., Mayer K. H., Krakower D. S., et al. Potential impact of doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis prescribing strategies on incidence of bacterial sexually transmitted infections. Clin Infect Dis 2023. [PMID: 37595139]

Vanbaelen T., Manoharan-Basil S. S., Kenyon C. Doxycycline postexposure prophylaxis could induce cross-resistance to other classes of antimicrobials in Neisseria gonorrhoeae: an in silico analysis. Sex Transm Dis 2023;50(8):490-93. [PMID: 36952471]

Werner R. N., Schmidt A. J., Potthoff A., et al. Position statement of the German STI Society on the prophylactic use of doxycycline to prevent STIs (doxy-PEP, doxy-PrEP). J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2024;22(3):466-78. [PMID: 38123738]

Wilson D. P., Prestage G. P., Gray R. T., et al. Chemoprophylaxis is likely to be acceptable and could mitigate syphilis epidemics among populations of gay men. Sex Transm Dis 2011;38(7):573-79. [PMID: 21343845]

Workowski K. A., Bachmann L. H., Chan P. A., et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep 2021;70(4):1-187. [PMID: 34292926]

Zaenglein A. L., Pathy A. L., Schlosser B. J., et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016;74(5):945-73.e33. [PMID: 26897386]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources | |

| Date of original publication | September 25, 2023 |

| Date of current publication | October 15, 2024 |

| Highlights of changes, additions, and updates in the October 15, 2024 edition |

|

| Intended users | New York State clinicians who provide medical care for individuals at risk of acquiring sexually transmitted infections |

| Lead author(s) |

Daniela E. DiMarco, MD, MPH; Marguerite A. Urban, MD |

| Writing group |

Rona M. Vail, MD, AAHIVS; Sanjiv S. Shah, MD, MPH, AAHIVM, AAHIVS; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA, AAHIVS; Samuel T. Merrick, MD, FIDSA; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD, FACP, AAHIVS; Jessica Rodrigues, MPH, MS; Brianna L. Norton, DO, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH, MSc, FACP |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures. |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

| Related NYSDOH AI resources |

Guidelines

Podcast |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on November 14, 2025