Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: December 11, 2024

Lead author: Ethan Cowan, MD, MS

Writing group: Rona M. Vail, MD, AAHIVS; Sanjiv S. Shah, MD, MPH, AAHIVS; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA, AAHIVS; Samuel T. Merrick, MD, FIDSA; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD, FACP, AAHIVS; Anne K. Monroe, MD, MSPH; Jessica Rodrigues, MPH, MS; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH, MSc, FACP; Brianna L. Norton, DO, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 24, 2018

This guideline on diagnosis and management of acute HIV infection was developed by the Medical Care Criteria Committee of New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) to guide clinicians in New York State who provide ambulatory, inpatient, and emergency medical care for adults aged ≥18 years who present with signs or symptoms of acute HIV infection or report an exposure within the past 4 weeks.

This guideline provides evidence-based clinical recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of acute HIV infection in adults, with the goals of ensuring that New York State clinicians are able to:

- Recognize the risks of and signs and symptoms of acute HIV, include HIV infection in the differential diagnosis, and consider HIV testing in any person who presents with signs and symptoms suggestive of influenza (“flu”), mononucleosis (“mono”), or other viral syndromes, including suspected COVID-19.

- Perform appropriate diagnostic and confirmatory testing when HIV infection is suspected and manage the treatment of acute HIV.

- Meet the New York State requirements for reporting and partner notification.

- Recommend or offer immediate initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART) to improve the patient’s health and reduce the risk of HIV transmission; refer and confirm that patients can access optimal HIV care.

- Initiate or refer the patient for prevention services.

| TERMINOLOGY |

|

Early diagnosis for early treatment: Accumulating evidence supports a decision to begin HIV treatment at the time of diagnosis Crowell, et al. 2024; Gabert, et al. 2023; Chéret, et al. 2022; Dijkstra, et al. 2021; Lama, et al. 2021; Martin, et al. 2021; Lundgren, et al. 2015. Initiation of ART during acute infection may have several beneficial clinical outcomes, including improved preservation of immunologic function, significantly reduced time to viral suppression, and reduction of the viral reservoir, which could be important for cure strategies Pilcher, et al. 2017; Chéret, et al. 2015; Margolick, et al. 2015; Phanuphak, et al. 2015; Buzon, et al. 2014; Le, et al. 2013; Saez-Cirion, et al. 2013; Ananworanich, et al. 2012; Hocqueloux, et al. 2010; Koegl, et al. 2009; Streeck, et al. 2006; Pires, et al. 2004. The risk of sexual transmission of HIV during acute or recent infection is significantly higher than during chronic infection Hollingsworth, et al. 2015; Hollingsworth, et al. 2008; Pinkerton 2008; Pilcher, et al. 2004; this difference likely correlates with high levels of viremia. The public health benefit of early ART initiation is well documented, with a significant reduction of HIV transmission among virally suppressed individuals. Further, in September 2017, the NYSDOH endorsed the consensus from the Prevention Access Campaign that undetectable = untransmittable (“U = U”), which indicates that individuals with a durable (≥6 months) undetectable viral load will not sexually transmit HIV Prevention Access Campaign 2018; NYSDOH 2017.

Recognizing and diagnosing acute HIV infection is crucial to linking patients to care early and presents an important opportunity to reduce HIV transmission. Factors that may contribute to the increased risk of transmission during acute infection include:

- Hyperinfectivity associated with both markedly high viral load levels (often much greater than 10 million viral copies/mm3) and increased infectiousness of the virus Ma, et al. 2009; Quinn, et al. 2000.

- Missed HIV diagnosis Nakao, et al. 2014; Chin, et al. 2013. Because the nonspecific flu- or mono-like symptoms are frequently unrecognized as symptoms of acute HIV infection or attributed to a nonspecific viral syndrome, the diagnosis is often missed. Missed diagnosis of acute HIV infection results in a lost opportunity to recommend treatment and risk-reduction counseling that could reduce both viral load levels and high-risk behavior Kroon, et al. 2017; Rutstein, et al. 2017; Fonner, et al. 2012; Steward, et al. 2009; Colfax, et al. 2002.

For many reasons, detecting acute HIV infection is an essential link in the chain of prevention. Evidence demonstrates that patients with a recent diagnosis of HIV are more likely to reduce risk behaviors if they are given counseling at the time of testing Fonner, et al. 2012; Steward, et al. 2009 and are linked to primary HIV care Metsch, et al. 2008. In addition, for those who elect to initiate ART, their risk of transmission is significantly diminished Cohen, et al. 2016; Cohen, et al. 2011.

| KEY POINTS |

|

| NEW YORK STATE LAW |

|

Note on “experienced” HIV care providers: The NYSDOH AI Clinical Guidelines Program defines an “experienced HIV care provider” as a practitioner who has been accorded HIV Specialist status by the American Academy of HIV Medicine. Nurse practitioners (NPs) and licensed midwives who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV in collaboration with a physician may be considered experienced HIV care providers if all other practice agreements are met; NPs with more than 3,600 hours of qualifying experience do not require collaboration with a physician (8 NYCRR 79-5:1; 10 NYCRR 85.36; 8 NYCRR 139-6900). Physician assistants who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV under the supervision of an HIV Specialist physician may also be considered experienced HIV care providers (10 NYCRR 94.2).

Presentation, Testing, and Diagnosis

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Presentation of Acute HIV Infection

Testing for Acute HIV Infection

Diagnosis of Acute HIV Infection

ART Initiation

Partner Notification

|

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; Ag, antigen; ART, antiretroviral therapy; NAT, nucleic acid test; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection. Notes:

|

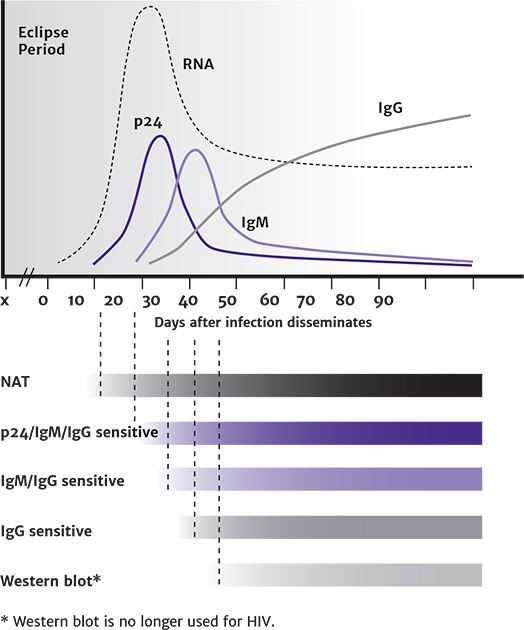

The time from HIV infection to detection of the virus depends on the test that is used. Figure 1, below, illustrates the window of detection of HIV infection according to Ab, Ag/Ab combination, and HIV RNA tests.

Figure 1: HIV Test Window of Detection [a,b,c]

Abbreviations: IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M; NAT, nucleic acid test; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis.

Notes:

- Figure reproduced from CDC: Clinical Testing Guidance for HIV.

- Without PrEP or PEP exposure; PrEP or PEP exposure may delay seroconversion. Very early treatment of acute HIV infection may also alter the serologic response Stekler, et al. 2023; Hare, et al. 2006; Kassutto, et al. 2005.

- The eclipse period is the time from the onset of HIV infection until the virus is detectable by virologic tests.

Download figure: HIV Test Window of Detection

Presentation

The presentation of acute HIV infection is highly variable. Fever and influenza- or mononucleosis-like symptoms are common in acute HIV infection but are nonspecific. Patients may also present with more specific symptoms of acute retroviral syndrome (see Box 1, below) such as rash, mucocutaneous ulcers, oropharyngeal candidiasis, lymphadenopathy and meningismus, which should raise the index of suspicion. The mean time from exposure to onset of symptoms is generally 2 to 4 weeks, with a range of 5 to 29 days; however, some cases have presented with symptoms up to 3 months after exposure Apoola, et al. 2002. This time course is prolonged and atypical in patients who become infected while on PEP or PrEP Landovitz, et al. 2024; Moschese, et al. 2024.

| Box 1: Acute Retroviral Syndrome |

|

Signs and symptoms of ARS with the expected frequency among symptomatic patients are listed below [a]. The most specific symptoms in this study were oral ulcers and weight loss; the best predictors were fever and rash. The index of suspicion should be high when these symptoms are present.

|

|

Note:

|

Testing and Diagnosis

Acute HIV infection is often not recognized in the primary care setting because the symptom profile is similar to that of influenza, mononucleosis, and other common illnesses. Furthermore, patients often do not recognize that they may have recently been exposed to HIV. Therefore, the clinician should have a high index of suspicion for acute HIV infection in a patient who may have recently engaged in behavior involving sexual or parenteral exposure to another individual’s blood or body fluids and who is presenting with a febrile, influenza-, or mononucleosis-like illness. Identifying acute HIV infection during pregnancy is particularly important because effective intervention can prevent mother-to-child transmission Patterson, et al. 2007.

High levels of HIV RNA detected in plasma through sensitive NAT, combined with a negative or indeterminate HIV screening or type-differentiation test, support the presumptive diagnosis of acute HIV infection DHHS 2024; Robb, et al. 2016. Reflex testing to HIV RNA when there are discordant results between an Ag/Ab combination immunoassay followed by a negative or indeterminate Ab differentiation immunoassay can both help to identify acute HIV infection and mitigate the need for the patient to return for confirmatory testing Kaperak, et al. 2024. While both quantitative and qualitative HIV-1 RNA assays have good sensitivity for detecting HIV-1 at a low threshold, quantitative tests are more widely available and preferred Wu, et al. 2017. An elevated signal-to-cutoff ratio (≥10) on laboratory-performed Ag/Ab combination immunoassays may help differentiate between acute HIV infection and a false-positive result Crowell, et al. 2021; Li, et al. 2018; Jensen, et al. 2015.

When low-level viremia is reported by HIV RNA testing (<200 copies/mL) in the absence of serologic confirmation of HIV infection, HIV RNA testing should be repeated to exclude a false-positive result Hecht, et al. 2002. Repeat HIV RNA testing with a result that indicates the presence of low-level viremia may represent true HIV infection, warranting appropriate counseling regarding transmission risk and initiation of ART.

HIV RNA levels tend to be very high in acute infection; however, a low value may represent any point on the upward or downward slope of the viremia associated with acute infection or could simply represent chronic infection. HIV RNA can also be suppressed during acute infection in patients who are taking PrEP. For patients taking long-acting injectable cabotegravir (CAB-LA) for PrEP, laboratory and clinical presentation of acute HIV infection can be difficult to interpret due to long-acting early viral inhibition (also known as LEVI syndrome) Landovitz, et al. 2024. Observation and frequent retesting may be needed to determine whether HIV infection has occurred in these patients, and consultation with an experienced HIV care provider is advised.

Plasma HIV RNA levels during acute infection do not appear significantly different in patients who are and are not symptomatic Patterson, et al. 2007. Viremia occurs approximately 1 to 2 weeks before the detection of a specific immune response. Patients diagnosed with acute infection by HIV RNA testing should always receive follow-up diagnostic testing 3 weeks later to confirm infection (see the standard HIV laboratory testing algorithm). Figure 2, below, illustrates diagnostic testing for acute HIV infection.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Figure 2: Diagnostic Testing for Acute HIV Infection

Notes:

- Viremia will be present several days prior to p24 antigen detection and several weeks before antibody detection.

- HIV RNA quantitative testing is preferred.

- The absence of serologic evidence of HIV infection is defined as nonreactive screening result (antibody or antibody/antigen combination) or a reactive screening result with a nonreactive or indeterminate antibody-differentiation confirmatory result.

- Serologic confirmation as defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV testing algorithm. Western blot is no longer recommended as the confirmatory test because it may yield an indeterminate result during the early stages of seroconversion and may delay confirmation of diagnosis.

- No further testing is indicated.

Management, Including While on PEP or PrEP

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Managing Acute HIV Infection

Initiating ART

|

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis. Note:

|

Patients are at greatest risk of transmitting HIV during periods of high viremia early in infection. Clinicians should counsel patients with acute HIV about the increased risk of transmission during the 6 months after acute infection and the ongoing risk of transmission beyond 6 months. Partner notification Golden, et al. 2004, counseling on safer sex, and screening for other sexually transmitted infections are all essential in the management of any new HIV diagnosis.

Consultation: When choosing an ART regimen for a patient with acute HIV infection, clinicians should consult a care provider experienced in treating acute HIV infection.

- Data are insufficient to support a specific ART regimen(s) for the treatment of acute HIV infection; instead, the choice of regimen should be made based on recommendations for selecting an initial ART regimen.

- The risks of transmitted resistance should be considered when prescribing ART while awaiting HIV resistance results.

- The risks of acquired mutations should be considered in those who acquire HIV while on PrEP.

- Clinicians who do not have access to experienced HIV care providers should call the CEI Line at 866-637-2342.

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS: DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE HIV INFECTION |

Presentation of Acute HIV Infection

Testing for Acute HIV Infection

Diagnosis of Acute HIV Infection

ART Initiation

Partner Notification

Managing Acute HIV Infection

Initiating ART

|

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; Ag, antigen; ART, antiretroviral therapy; NAT, nucleic acid test; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STI, sexually transmitted infection. Notes:

|

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

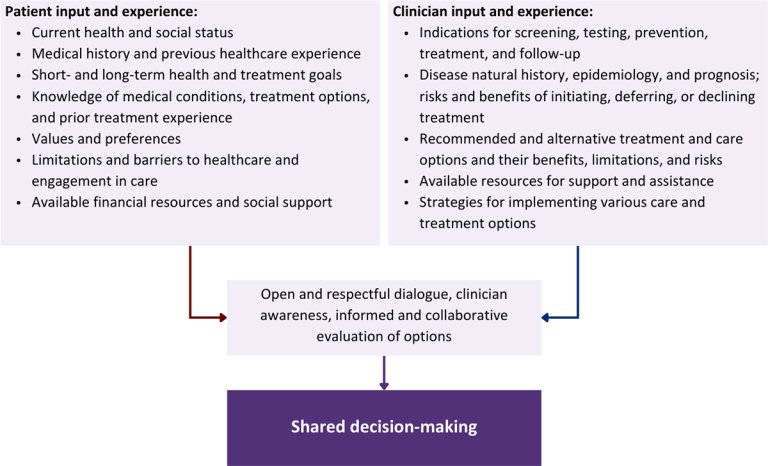

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Ananworanich J., Schuetz A., Vandergeeten C., et al. Impact of multi-targeted antiretroviral treatment on gut T cell depletion and HIV reservoir seeding during acute HIV infection. PLoS One 2012;7(3):e33948. [PMID: 22479485]

Apoola A., Ahmad S., Radcliffe K. Primary HIV infection. Int J STD AIDS 2002;13(2):71-78. [PMID: 11839160]

Buzon M. J., Martin-Gayo E., Pereyra F., et al. Long-term antiretroviral treatment initiated at primary HIV-1 infection affects the size, composition, and decay kinetics of the reservoir of HIV-1-infected CD4 T cells. J Virol 2014;88(17):10056-65. [PMID: 24965451]

Chéret A., Bacchus-Souffan C., Avettand-Fenoël V., et al. Combined ART started during acute HIV infection protects central memory CD4+ T cells and can induce remission. J Antimicrob Chemother 2015;70(7):2108-20. [PMID: 25900157]

Chéret A., Bauer R., Meiffrédy V., et al. Once-daily dolutegravir versus darunavir plus cobicistat in adults at the time of primary HIV-1 infection: the OPTIPRIM2-ANRS 169 randomized, open-label, Phase 3 trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 2022;77(9):2506-15. [PMID: 35762503]

Chin T., Hicks C., Samsa G., et al. Diagnosing HIV infection in primary care settings: missed opportunities. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27(7):392-97. [PMID: 23802143]

Cohen M. S., Chen Y. Q., McCauley M., et al. Antiretroviral therapy for the prevention of HIV-1 transmission. N Engl J Med 2016;375(9):830-39. [PMID: 27424812]

Cohen M. S., Chen Y. Q., McCauley M., et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2011;365(6):493-505. [PMID: 21767103]

Colfax G. N., Buchbinder S. P., Cornelisse P. G., et al. Sexual risk behaviors and implications for secondary HIV transmission during and after HIV seroconversion. AIDS 2002;16(11):1529-35. [PMID: 12131191]

Crowell T. A., Ritz J., Coombs R. W., et al. Novel criteria for diagnosing acute and early human immunodeficiency virus infection in a multinational study of early antiretroviral therapy initiation. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73(3):e643-51. [PMID: 33382405]

Crowell T. A., Ritz J., Zheng L., et al. Impact of antiretroviral therapy during acute or early HIV infection on virologic and immunologic outcomes: results from a multinational clinical trial. AIDS 2024;38(8):1141-52. [PMID: 38489580]

DHHS. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV: early (acute and recent) HIV infection. 2024 Sep 12. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/adult-and-adolescent-arv/acute-and-recent-early-hiv-infection [accessed 2021 Jun 29]

Dijkstra M., van Rooijen M. S., Hillebregt M. M., et al. Decreased time to viral suppression after implementation of targeted testing and immediate initiation of treatment of acute human immunodeficiency virus infection among men who have sex with men in Amsterdam. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(11):1952-60. [PMID: 32369099]

Fonner V. A., Denison J., Kennedy C. E., et al. Voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) for changing HIV-related risk behavior in developing countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9(9):CD001224. [PMID: 22972050]

Gabert R., Lama J. R., Valdez R., et al. Acute retroviral syndrome is associated with lower CD4 + T cell nadir and delayed viral suppression, which are blunted by immediate antiretroviral therapy initiation. AIDS 2023;37(7):1103-8. [PMID: 36779502]

Golden M. R., Hogben M., Potterat J. J., et al. HIV partner notification in the United States: a national survey of program coverage and outcomes. Sex Transm Dis 2004;31(12):709-12. [PMID: 15608584]

Hare C. B., Pappalardo B. L., Busch M. P., et al. Seroreversion in subjects receiving antiretroviral therapy during acute/early HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42(5):700-708. [PMID: 16447118]

Hecht F. M., Busch M. P., Rawal B., et al. Use of laboratory tests and clinical symptoms for identification of primary HIV infection. AIDS 2002;16(8):1119-29. [PMID: 12004270]

Hocqueloux L., Prazuck T., Avettand-Fenoel V., et al. Long-term immunovirologic control following antiretroviral therapy interruption in patients treated at the time of primary HIV-1 infection. AIDS 2010;24(10):1598-1601. [PMID: 20549847]

Hollingsworth T. D., Anderson R. M., Fraser C. HIV-1 transmission, by stage of infection. J Infect Dis 2008;198(5):687-93. [PMID: 18662132]

Hollingsworth T. D., Pilcher C. D., Hecht F. M., et al. High transmissibility during early HIV infection among men who have sex with men-San Francisco, California. J Infect Dis 2015;211(11):1757-60. [PMID: 25542958]

Jensen T. O., Robertson P., Whybin R., et al. A signal-to-cutoff ratio in the Abbott architect HIV Ag/Ab Combo assay that predicts subsequent confirmation of HIV-1 infection in a low-prevalence setting. J Clin Microbiol 2015;53(5):1709-11. [PMID: 25673794]

Kaperak C., Eller D., Devlin S. A., et al. Reflex human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) type 1 RNA testing enables timely differentiation of false-positive results from acute HIV infection. Open Forum Infect Dis 2024;11(1):ofad629. [PMID: 38269050]

Kassutto S., Johnston M. N., Rosenberg E. S. Incomplete HIV type 1 antibody evolution and seroreversion in acutely infected individuals treated with early antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40(6):868-73. [PMID: 15736021]

Koegl C., Wolf E., Hanhoff N., et al. Treatment during primary HIV infection does not lower viral set point but improves CD4 lymphocytes in an observational cohort. Eur J Med Res 2009;14(7):277-83. [PMID: 19661009]

Kroon Edmb, Phanuphak N., Shattock A. J., et al. Acute HIV infection detection and immediate treatment estimated to reduce transmission by 89% among men who have sex with men in Bangkok. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20(1):21708. [PMID: 28691441]

Lama J. R., Ignacio R. A. B., Alfaro R., et al. Clinical and immunologic outcomes after immediate or deferred antiretroviral therapy initiation during primary human immunodeficiency virus infection: the Sabes randomized clinical study. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(6):1042-50. [PMID: 32107526]

Landovitz R. J., Delany-Moretlwe S., Fogel J. M., et al. Features of HIV infection in the context of long-acting cabotegravir preexposure prophylaxis. N Engl J Med 2024. [PMID: 39046350]

Le T., Wright E. J., Smith D. M., et al. Enhanced CD4+ T-cell recovery with earlier HIV-1 antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med 2013;368(3):218-30. [PMID: 23323898]

Li L., Puddicombe D., Champagne S., et al. HIV serology signal-to-cutoff ratio as a rapid method to predict confirmation of HIV infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2018;37(8):1589-93. [PMID: 29862422]

Lundgren J. D., Babiker A. G., Gordin F., et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy in early asymptomatic HIV infection. N Engl J Med 2015;373(9):795-807. [PMID: 26192873]

Ma Z. M., Stone M., Piatak M., et al. High specific infectivity of plasma virus from the pre-ramp-up and ramp-up stages of acute simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol 2009;83(7):3288-97. [PMID: 19129448]

Margolick J. B., Apuzzo L., Singer J., et al. A randomized trial of time-limited antiretroviral therapy in acute/early HIV infection. PLoS One 2015;10(11):e0143259. [PMID: 26600459]

Martin T. C. S., Abrams M., Anderson C., et al. Rapid antiretroviral therapy among individuals with acute and early HIV. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73(1):130-33. [PMID: 32777035]

Metsch L. R., Pereyra M., Messinger S., et al. HIV transmission risk behaviors among HIV-infected persons who are successfully linked to care. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47(4):577-84. [PMID: 18624629]

Moschese D., Lazzarin S., Colombo M. L., et al. Breakthrough acute HIV infections among pre-exposure prophylaxis users with high adherence: a narrative review. Viruses 2024;16(6):951. [PMID: 38932243]

Nakao J. H., Wiener D. E., Newman D. H., et al. Falling through the cracks? Missed opportunities for earlier HIV diagnosis in a New York City Hospital. Int J STD AIDS 2014;25(12):887-93. [PMID: 24535693]

NYSDOH. Dear colleague letter. 2017 Sep. https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/ending_the_epidemic/docs/september_physician_letter.pdf [accessed 2018 Aug 21]

Patterson K. B., Leone P. A., Fiscus S. A., et al. Frequent detection of acute HIV infection in pregnant women. AIDS 2007;21(17):2303-8. [PMID: 18090278]

Phanuphak N., Teeratakulpisarn N., van Griensven F., et al. Anogenital HIV RNA in Thai men who have sex with men in Bangkok during acute HIV infection and after randomization to standard vs. intensified antiretroviral regimens. J Int AIDS Soc 2015;18(1):19470. [PMID: 25956171]

Pilcher C. D., Ospina-Norvell C., Dasgupta A., et al. The effect of same-day observed initiation of antiretroviral therapy on HIV viral load and treatment outcomes in a US public health setting. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2017;74(1):44-51. [PMID: 27434707]

Pilcher C. D., Tien H. C., Eron J. J., et al. Brief but efficient: acute HIV infection and the sexual transmission of HIV. J Infect Dis 2004;189(10):1785-92. [PMID: 15122514]

Pinkerton S. D. Probability of HIV transmission during acute infection in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Behav 2008;12(5):677-84. [PMID: 18064559]

Pires A., Hardy G., Gazzard B., et al. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy during recent HIV-1 infection results in lower residual viral reservoirs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2004;36(3):783-90. [PMID: 15213561]

Prevention Access Campaign. Risk of sexual transmission of HIV from a person living with HIV who has an undetectable viral load: messaging primer & consensus statement. 2018 Jan 10. https://preventionaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/UU-Consensus-Statement.pdf [accessed 2018 Aug 21]

Quinn T. C., Wawer M. J., Sewankambo N., et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med 2000;342(13):921-29. [PMID: 10738050]

Robb M. L., Eller L. A., Kibuuka H., et al. Prospective study of acute HIV-1 infection in adults in East Africa and Thailand. N Engl J Med 2016;374(22):2120-30. [PMID: 27192360]

Rutstein S. E., Ananworanich J., Fidler S., et al. Clinical and public health implications of acute and early HIV detection and treatment: a scoping review. J Int AIDS Soc 2017;20(1):21579. [PMID: 28691435]

Saez-Cirion A., Bacchus C., Hocqueloux L., et al. Post-treatment HIV-1 controllers with a long-term virological remission after the interruption of early initiated antiretroviral therapy ANRS VISCONTI Study. PLoS Pathog 2013;9(3):e1003211. [PMID: 23516360]

Stekler J. D., Violette L. R., Niemann L. A., et al. Seroconversion, seroreversion, and serowaffling among participants initiating antiretroviral therapy in Project DETECT. Int J STD AIDS 2023;34(6):385-94. [PMID: 36703607]

Steward W. T., Remien R. H., Higgins J. A., et al. Behavior change following diagnosis with acute/early HIV infection-a move to serosorting with other HIV-infected individuals. The NIMH Multisite Acute HIV Infection Study: III. AIDS Behav 2009;13(6):1054-60. [PMID: 19504178]

Streeck H., Jessen H., Alter G., et al. Immunological and virological impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy initiated during acute HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis 2006;194(6):734-39. [PMID: 16941338]

Suanzes P., Navarro J., Rando-Segura A., et al. Impact of very early antiretroviral therapy during acute HIV infection on long-term immunovirological outcomes. Int J Infect Dis 2023;136:100-106. [PMID: 37726066]

Wu H., Cohen S. E., Westheimer E., et al. Diagnosing acute HIV infection: the performance of quantitative HIV-1 RNA testing (viral load) in the 2014 laboratory testing algorithm. J Clin Virol 2017;93:85-86. [PMID: 28342746]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources | |

| Date of original publication | August 24, 2018 |

| Date of current publication | December 11, 2024 |

| Highlights of changes, additions, and updates in the December 11, 2024 edition |

|

| Intended users | Clinicians in New York State who provide ambulatory, inpatient, and emergency medical care for adults aged ≥18 years who present with signs or symptoms of acute HIV infection or report an exposure within the past 4 weeks |

| Lead author |

Ethan Cowan, MD, MS |

| Writing group |

Rona M. Vail, MD, AAHIVS; Sanjiv S. Shah, MD, MPH, AAHIVS; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA, AAHIVS; Samuel T. Merrick, MD, FIDSA; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD, FACP, AAHIVS; Anne K. Monroe, MD, MSPH; Jessica Rodrigues, MPH, MS; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH, MSc, FACP; Brianna L. Norton, DO, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures. |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

| Related NYSDOH AI resources |

Guidelines

Podcast |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on November 6, 2025