Purpose of This Guidance

Date of current publication: February 19, 2026

Lead author: Marguerite A. Urban, MD; Maria Teresa Timoney, CNM, NP, MS, RN

Writing group: Rona M. Vail, MD, AAHIVS; Sanjiv S. Shah, MD, MPH, AAHIVS; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Samuel T. Merrick, MD, FIDSA; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD, FACP, AAHIVS; Anne K. Monroe, MD, MSPH; Jessica Rodrigues, MPH, MS; Brianna L. Norton, DO, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH, MSc, FACP

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: February 19, 2026

This guidance was developed by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) Clinical Guidelines Program to guide clinicians providing care to patients with bacterial vaginosis (BV). The goals of this guidance are to:

- Educate clinicians about BV symptoms, prevalence, risk factors, and treatments, and the potential for recurrence after treatment.

- Outline current evidence for partner treatment of individuals with BV to prevent recurrence.

- Discuss appropriate treatment for individuals with BV and their sex partners.

Existing data are conflicting regarding the efficacy of partner treatment on BV recurrence; however, a recent study showed a clear preventive benefit from the concomitant treatment of male partners (with oral plus topical antibiotics) of individuals with BV, with a more than 60% reduction in BV recurrences Vodstrcil, et al. 2025; Vodstrcil, et al. 2020. Further research is needed to determine if these results can be replicated in different populations, including those with high rates of circumcision, in which the impact of topical therapy may be lower. However, given that symptomatic recurrent BV can lead to stigma, lifestyle disruption, and multiple courses of antibiotics, this guidance supports offering antibiotic treatment to ongoing sex partners of individuals diagnosed with symptomatic BV.

Other guidance: In October 2025, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology released a clinical practice update supporting partner treatment for ongoing partners of individuals with BV ACOG 2025.

Bacterial Vaginosis: An Overview

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is a common clinical condition associated with symptoms of vaginal discharge and fishy or amine odor. BV is reported to be the most common cause of vaginal discharge worldwide among individuals of childbearing age. Worldwide prevalence of BV varies significantly, with regional prevalence estimates ranging from 20% to 60% Coudray and Madhivanan 2020. In the United States, the prevalence of BV has been estimated as 29% among the general population Peebles, et al. 2019, and BV is more commonly identified among Black and Hispanic women than White women for reasons that are not well understood Allsworth and Peipert 2007. Data are lacking about the prevalence of BV in transgender individuals.

BV is classified as a dysbiosis, referring to the shift in the vaginal bacterial microbiota from a predominance of lactobacilli to a mixed population of bacteria with high concentrations of facultative anaerobes (including Gardnerella vaginalis, Prevotella species, and others) Plummer, et al. 2023; Kenyon, et al. 2018. BV has also been associated with increased transmission and acquisition of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), chorioamnionitis, risk of spontaneous abortion, preterm labor, and postprocedural and postpartum endometritis Muzny, et al. 2022; Workowski, et al. 2021.

Risk factors: The pathogenesis of BV is not entirely understood, although studies have documented an association between BV and sexual activity (BV is rarely reported before the onset of sexual activity) as well as risk factors suggesting sexual transmission of BV-associated bacteria Abou Chacra, et al. 2023; Roxby, et al. 2023; Muzny, et al. 2022; Vodstrcil, et al. 2021; Fethers, et al. 2009; Wiesenfeld, et al. 2003. Factors associated with BV include new or multiple sex partners, lack of condom use, and the presence of other STIs. BV-associated bacteria have been identified on male genitalia of sex partners of individuals with BV, suggesting an exchange of organisms through sexual intercourse Vodstrcil, et al. 2021. BV with a high genetic concordance of organisms has been found in both partners within couples of women who have sex with women Vodstrcil, et al. 2021.

Recurrence: BV symptoms often respond to treatment with oral or topical antibiotics directed at anaerobic bacteria, but there are very high rates of recurrent episodes leading to negative impacts on quality of life, frequent health care visits, and repeated use of antibiotics. Recurrent BV has been associated with having an ongoing sexual partnership, lack of condom use, presence of an IUD, and having an uncircumcised sex partner Muzny, et al. 2022; Ratten, et al. 2021; Bradshaw, et al. 2013; Bradshaw, et al. 2006. Recurrent BV remains a difficult clinical problem for clinicians and patients, with more than 50% of individuals developing a recurrence within 6 months of diagnosis Ratten, et al. 2021; Vodstrcil, et al. 2021; Bradshaw, et al. 2013. There are no universally effective interventions to prevent recurrences. Despite evidence of an association with sexual activity, until recently, there has not been convincing evidence that the treatment of sex partners decreases recurrences of BV Schwebke, et al. 2021; Amaya-Guio, et al. 2016.

Evidence on Partner Treatment

The StepUp trial: Monogamous heterosexual cisgender couples were enrolled in the multicenter, randomized, open-label StepUp trial, conducted in Australia, to assess whether concomitant partner treatment could decrease recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis (BV) among women receiving treatment Vodstrcil, et al. 2025; Vodstrcil, et al. 2020. Premenopausal cisgender women aged 18 years or older diagnosed with symptomatic BV who reported monogamy with a cisgender male partner for 8 weeks before enrollment and an intention to remain monogamous for 12 weeks after enrollment were included. BV was diagnosed using Amsel’s criteria or Nugent score (see Box 1: Diagnosing Bacterial Vaginosis). Male partners were referred for study participation by their partners and enrolled within 1 week of their partner’s BV diagnosis. Exclusions included HIV infection, sex work, having other concurrent sexual partners, PID, being pregnant or breastfeeding, using other antibiotics, or having a contraindication to the study antibiotics. Couples were randomized 1:1 and stratified by clinic site at enrollment, circumcision status of the male partner, and presence of an intrauterine device (IUD) in the female partner. Male partners were asymptomatic. Couples received standard BV treatment of the female partner with no associated male partner treatment (control group) or standard BV treatment of the female partner and simultaneous male partner treatment (partner treatment group). Participants with BV received treatment with oral metronidazole 400 mg twice daily for 7 days, intravaginal 2% clindamycin cream for 7 nights, or intravaginal 0.75% metronidazole gel for 5 nights. The treatment regimen for male partners was oral metronidazole 400 mg twice daily for 7 days plus 2% clindamycin cream applied topically to the penis twice daily for 7 days. All participants were counselled to avoid sex until antibiotic treatments were completed. Follow-up evaluations included symptom questionnaires and vaginal samples, which were used to assess for BV by Nugent score and obtained at day 8 and weeks 4, 8, and 12.

The study was discontinued early after a Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) review showed a significant reduction in BV recurrences within 12 weeks of partner treatment Vodstrcil, et al. 2025. In modified intent-to-treat analysis, BV recurrences were identified in 24 of 69 women (35%) in the partner treatment group (recurrence rate, 1.6 per person-year; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.1-2.4) and in 43 of 68 women (63%) in the control group for (recurrence rate, 4.2 per person-year; 95% CI, 3.2-5.7) corresponding to an absolute risk difference of -2.6 recurrences per person-year (95% CI, -4.0 to -1.2; P<.001). Mean time to recurrence was 73.9 days in the partner treatment group and 54.5 days in the control group (difference in days to recurrence, 19.3 days; 95% CI, 11.5 to 27.1; P<.001). No significant adverse events were reported. Among women treated with metronidazole, approximately 60% in both groups reported some adverse symptom, most commonly nausea, headache, and vaginal itch. Among men who completed a questionnaire, 46% reported symptoms including nausea, headache, and metallic taste. Local penile symptoms of redness or irritation were rare (reported by 4 participants). The population enrolled in the trial had a high likelihood for recurrences due to several factors, as 87% of women enrolled had prior BV, 80% had an uncircumcised male partner, and 30% had an IUD, making the reduction in recurrences particularly notable. Adherence to the treatment regimen among the male partners was high (lower for the topical therapy than for the oral metronidazole) and recurrence rates were lowest among women whose partners were highly adherent. Results did not differ by presence or absence of an IUD or circumcision status.

Other studies: Prior studies by the same research group from the StepUp trial showed that the use of combination oral and topical antibiotic therapy (as used in StepUp) affected the microbiota of the penis at the urethra and skin in the subpreputial space (beneath the foreskin), with a reduction of BV-associated bacteria detected after antimicrobial treatment Plummer, et al. 2021; Plummer, et al. 2018.

Other studies directly evaluating the impact of partner treatment on BV recurrences have not shown efficacy Schwebke, et al. 2021; Peebles, et al. 2019. None of the prior partner treatment trials included a topical antibiotic as was done in the StepUp trial. A comprehensive Cochrane analysis review published in 2017 evaluated 7 trials published between 1985 and 1997 examining oral antibiotic treatment (4 used metronidazole, 2 used tinidazole, 1 used clindamycin) of male sex partners of individuals diagnosed with BV Amaya-Guio, et al. 2016. The authors of the analysis concluded that oral antibiotic treatment did not decrease BV recurrence rate, concurring with existing Centers for Disease Control and Prevention STI treatment guidelines to not recommend partner treatment in the setting of a BV diagnosis Workowski, et al. 2021.

In 2025, the StepUp study team published (in supplementary materials) an updated review of 7 prior trials of partner treatment for BV Vodstrcil, et al. 2025, including 6 of the studies reported on in the Cochrane review and an additional U.S.-based trial published in 2021. None of the 7 studies showed a significant effect of male partner treatment on BV recurrences, although the authors cite significant methodologic issues that may have impacted the results (lack of reporting of adherence, sample size issues, and frequent use of single-dose regimens for participants with BV and their partners) in the 6 older trials.

In contrast, a 2021 trial conducted in Alabama was well-designed and well-powered to show an effect of partner treatment on BV recurrence but was stopped early after a DSMB review revealed futility (i.e., no evidence of effect of partner treatment on BV recurrences) Schwebke, et al. 2021. Therapy for participants with BV and their partners consisted of oral metronidazole 500 mg twice daily for 1 week. The study authors noted an unexpectedly high rate of initial BV treatment failure that may have been affected by adherence issues or could suggest that BV biofilms were already well-established and thus BV in these participants was complicated and no longer susceptible to partner treatment. Individuals with BV whose cisgender male partners adhered to study medication were less likely to experience treatment failure (adjusted relative risk, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.73–0.99; P=.035). It was postulated that the addition of topical antibiotic partner therapy might have affected results. However, this study population had a higher rate of Black participants with BV, higher rates of circumcision in partners, and lower rates of intrauterine device use than the Australian StepUp population (discussed above), which did add topical antibiotic to the partner regimen.

Patient and Partner Treatment

Diagnosing and Treating Patients With BV

Bacterial vaginosis (BV) is diagnosed using Amsel criteria, commercial assay, or Nugent score (see Box 1, below).

| Box 1: Diagnosing Bacterial Vaginosis |

|

The following methods, listed in alphabetical order, can be used to diagnose bacterial vaginosis (BV):

|

Once diagnosed, symptomatic BV can be treated with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–recommended regimen (see Box 2, below) Workowski, et al. 2021. When discussing a BV diagnosis with patients, it is important to inform the patient that BV is associated with sexual transmission and effective management may require the involvement of their sex partners. This language, with its emphasis on sexual transmission, is a change from how BV pathogenesis and natural history have been historically presented to patients and may trigger questions from patients with a prior history of BV. Essential points to discuss with patients with BV include the following:

- The BV-associated bacteria in the vagina that cause vaginal discharge and fishy odor can also be carried on the penises (with no symptoms) or in the vaginas of regular sex partners.

- There are no tests available to identify BV associated bacteria on male genitalia, however, research studies have shown high rates of concordance of bacteria in the genital tracts among regular sexual partners.

- Although evidence demonstrates that BV associated bacteria are shared between sex partners, it is important to inform patients and their partners that the sexual transmission of bacteria associated with BV refers to the sharing of endogenous bacteria not the introduction of exogenous pathogens such as gonorrhea or T. pallidum from an outside sexual encounter.

- The StepUp trial demonstrated that concurrent patient and partner treatment (despite no symptoms in the partner) among monogamous heterosexual couples reduced the rate of recurrences of BV and delayed those BV recurrences that did still occur Vodstrcil, et al. 2025; Vodstrcil, et al. 2020. No data are currently available about BV treatment for multiple partners.

| Box 2: Treatments for Bacterial Vaginosis [a] |

|

Recommended treatments for bacterial vaginosis are as follows:

|

|

Note: |

When treating patients with BV who have ongoing sexual partnerships, advise them that BV recurrences may be prevented or delayed when ongoing partners with a penis receive partner treatment through their primary care provider or a sexual health care provider. Partners with vaginas may seek further evaluation (see discussion below). If partners plan to seek treatment, advise the patient and partner to abstain from sexual activity until both have completed their treatment course. If sex occurs before treatment is complete, condoms should be used. Intravaginal clindamycin cream may weaken latex or rubber condoms FDA 2025; there are no data regarding condom use and topical penile clindamycin cream, although recent use of topical clindamycin cream on the penis may have a similar effect on condoms FDA 2025; Lexidrug 2025.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Treating Partners to Prevent Recurrent BV

As previously discussed, cisgender male sex partners of individuals with BV typically have no symptoms related to BV-associated bacteria. BV is not a sexually transmitted infection (STI) eligible for the use of expedited partner treatment in New York State; therefore, asymptomatic male partners will require an in-person or telehealth visit with a clinician to receive a prescription for the partner treatment.

When meeting with male sex partners of patients with BV:

- Obtain a sexual history. See NYSDOH GOALS Framework for Sexual History Taking in Primary Care.

- Establish that they are an existing partner and will be an ongoing partner of the individual diagnosed with BV.

- Provide education on the role of sexual transmission of BV-associated bacteria in BV recurrence, the effect of partner treatment on the rate of BV recurrence, the importance of adherence to both medications (oral and cream).

- Offer treatment with metronidazole 500 mg orally twice daily for 7 days plus 2% clindamycin cream applied to the head (beneath foreskin if present) and shaft of the penis twice daily for 7 days (adapted for United States medication formulations) Vodstrcil, et al. 2025; Vodstrcil, et al. 2020.

- Advise that the partner and primary patient abstain from sexual activity until both have completed their treatment course. If sex occurs before treatment is complete, condoms should be used. Counsel partners that intravaginal clindamycin cream may weaken condoms and that recent use of topical clindamycin cream on the penis may have a similar effect FDA 2025; Lexidrug 2025.

- Offer HIV and other STI screening and prevention services indicated by sexual history. See the NYSDOH guidelines HIV Testing, PrEP to Prevent HIV and Promote Sexual Health, and Doxycycline Post-Exposure Prophylaxis to Prevent Bacterial Sexually Transmitted Infections for additional information.

Metronidazole and clindamycin 2% cream are readily available, but care should be taken in the phrasing of the clindamycin cream instructions. In the United States, clindamycin 2% cream is distributed solely for vaginal use and dispensed with a vaginal applicator, leading some pharmacists to question or deny prescriptions with instructions for dermal use on the penis. As of August 2025, Micromedex and Lexidrug added topical use of clindamycin 2% cream on the penis as an off-label indication based on data from the StepUp trial Vodstrcil, et al. 2025; Vodstrcil, et al. 2020. Clindamycin 2% vaginal gel is not recommended for use on the penis. There are no data regarding the effectiveness of clindamycin 1% topical preparations as partner treatment for BV.

The prescription for clindamycin 2% cream should instruct the pharmacist that no vaginal applicators are necessary. To minimize delays in filling the prescriptions, it may be helpful to acknowledge that the prescription is an off-label use of the medication and provide the reference to the StepUp trial.

Patients can be given detailed instructions regarding clindamycin administration:

- Squeeze a line of cream from the tip of their index finger to the first crease.

- Retract foreskin, if uncircumcised, and rub the cream over the penile head and into the groove below the head.

- Squeeze a second line of cream onto their finger and rub it over the full length of the penile shaft, front and back and down to the base of the penis.

- Repeat this process twice daily for 7 days while taking oral metronidazole tablets.

- See Melbourne Sexual Health Centre Metronidazole and Clindamycin Instructions for Partners With a Penis for more information.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Partners outside a monogamous partnership: There are no data regarding treatment of sex partners outside a monogamous partnership; however, it would be prudent to treat all ongoing sex partners using the same approach.

Prior partners: There is no indication to treat prior sex partners (who would not be ongoing), as the goal of partner treatment is to prevent BV recurrence in the initial patient.

Female partners: There are also no data regarding treatment of female sex partners of individuals with BV. Ongoing sex partners with vaginas can be tested for BV using standard methods (see Box 1, above); if BV is identified, or if, after shared decision-making, treatment of an asymptomatic partner is undertaken, standard BV treatment (see Box 2, above) can be used, with no need for 2-drug therapy (oral plus cream).

Transgender or gender nonconforming partners: Data regarding treatment of transgender or gender nonconforming partners of individuals with BV are also lacking. For individuals who have undergone gender-affirming genital surgery, a shared decision-making approach can be used based on their anatomy. Treatment can be offered to partners with a penis as discussed above.

Future directions: Research trials evaluating the pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of BV are ongoing. The StepUp trial has continued to evaluate participants through an open-label extension study, and the same research group has initiated a study focused on people who identify as LGBTQIA+ (PACT study). This guidance will be updated as more information becomes available regarding partner treatment for the prevention of BV.

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

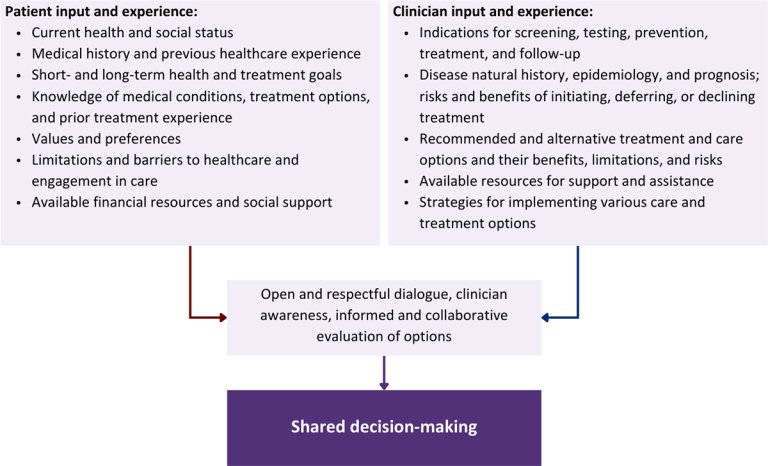

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Abou Chacra L., Ly C., Hammoud A., et al. Relationship between bacterial vaginosis and sexually transmitted infections: coincidence, consequence or co-transmission?. Microorganisms 2023;11(10):2470. [PMID: 37894128]

ACOG. Concurrent sexual partner therapy to prevent bacterial vaginosis recurrence. Obstet Gynecol 2025;46(6):e111-14. [PMID: 41100865]

Allsworth J. E., Peipert J. F. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis: 2001-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey data. Obstet Gynecol 2007;109(1):114-20. [PMID: 17197596]

Amaya-Guio J., Viveros-Carreno D. A., Sierra-Barrios E. M., et al. Antibiotic treatment for the sexual partners of women with bacterial vaginosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;10(10):CD011701. [PMID: 27696372]

Bradshaw C. S., Morton A. N., Hocking J., et al. High recurrence rates of bacterial vaginosis over the course of 12 months after oral metronidazole therapy and factors associated with recurrence. J Infect Dis 2006;193(11):1478-86. [PMID: 16652274]

Bradshaw C. S., Vodstrcil L. A., Hocking J. S., et al. Recurrence of bacterial vaginosis is significantly associated with posttreatment sexual activities and hormonal contraceptive use. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56(6):777-86. [PMID: 23243173]

Coudray M. S., Madhivanan P. Bacterial vaginosis-A brief synopsis of the literature. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2020;245:143-48. [PMID: 31901667]

FDA. Clindesse (clindamycin phosphate) vaginal cream, 2%. 2025 Nov. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2025/050793s033lbl.pdf [accessed 2025 Dec 1]

Fethers K. A., Fairley C. K., Morton A., et al. Early sexual experiences and risk factors for bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis 2009;200(11):1662-70. [PMID: 19863439]

Kenyon C. R., Buyze J., Klebanoff M., et al. Association between bacterial vaginosis and partner concurrency: a longitudinal study. Sex Transm Infect 2018;94(1):75-77. [PMID: 27645157]

King A. J., Phillips T. R., Plummer E. L., et al. Getting everyone on board to break the cycle of bacterial vaginosis (BV) recurrence: a qualitative study of partner treatment for BV. Patient 2025;18(3):279-90. [PMID: 40085319]

Lexidrug. Clindamycin (topical) (Lexi-Drugs). 2025 Oct 28. https://online.lexi.com/lco/action/doc/retrieve/docid/patch_f/1770162?cesid=3D1U68UafTw&searchUrl=%2Flco%2Faction%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Dclindamycin%26t%3Dname%26acs%3Dfalse%26acq%3Dclindamycin [accessed 2025 Nov 14]

Muzny C. A., Balkus J., Mitchell C., et al. Diagnosis and management of bacterial vaginosis: summary of evidence reviewed for the 2021 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines. Clin Infect Dis 2022;74(Suppl_2):S144-51. [PMID: 35416968]

Peebles K., Velloza J., Balkus J. E., et al. High global burden and costs of bacterial vaginosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Dis 2019;46(5):304-11. [PMID: 30624309]

Plummer E. L., Sfameni A. M., Vodstrcil L. A., et al. Prevotella and gardnerella are associated with treatment failure following first-line antibiotics for bacterial vaginosis. J Infect Dis 2023;228(5):646-56. [PMID: 37427495]

Plummer E. L., Vodstrcil L. A., Danielewski J. A., et al. Combined oral and topical antimicrobial therapy for male partners of women with bacterial vaginosis: Acceptability, tolerability and impact on the genital microbiota of couples - A pilot study. PLoS One 2018;13(1):e0190199. [PMID: 29293559]

Plummer E. L., Vodstrcil L. A., Doyle M., et al. A prospective, open-label pilot study of concurrent male partner treatment for bacterial vaginosis. mBio 2021;12(5):e0232321. [PMID: 34663095]

Ratten L. K., Plummer E. L., Murray G. L., et al. Sex is associated with the persistence of non-optimal vaginal microbiota following treatment for bacterial vaginosis: a prospective cohort study. BJOG 2021;128(4):756-67. [PMID: 33480468]

Roxby A. C., Mugo N. R., Oluoch L. M., et al. Low prevalence of bacterial vaginosis in Kenyan adolescent girls and rapid incidence after first sex. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2023;229(3):282.e1-282.e11. [PMID: 37391005]

Schwebke J. R., Lensing S. Y., Lee J., et al. Treatment of male sexual partners of women with bacterial vaginosis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Infect Dis 2021;73(3):e672-79. [PMID: 33383580]

Vodstrcil L. A., Muzny C. A., Plummer E. L., et al. Bacterial vaginosis: drivers of recurrence and challenges and opportunities in partner treatment. BMC Med 2021;19(1):194. [PMID: 34470644]

Vodstrcil L. A., Plummer E. L., Doyle M., et al. Treating male partners of women with bacterial vaginosis (StepUp): a protocol for a randomised controlled trial to assess the clinical effectiveness of male partner treatment for reducing the risk of BV recurrence. BMC Infect Dis 2020;20(1):834. [PMID: 33176727]

Vodstrcil L. A., Plummer E. L., Fairley C. K., et al. Male-partner treatment to prevent recurrence of bacterial vaginosis. N Engl J Med 2025;392(10):947-57. [PMID: 40043236]

Wiesenfeld H. C., Hillier S. L., Krohn M. A., et al. Bacterial vaginosis is a strong predictor of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Clin Infect Dis 2003;36(5):663-68. [PMID: 12594649]

Workowski K. A., Bachmann L. H., Chan P. A., et al. Sexually transmitted infections treatment guidelines, 2021. MMWR Recomm Rep 2021;70(4):1-187. [PMID: 34292926]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources | |

| Date of original publication | February 19, 2026 |

| Intended users | Clinicians who provide care for patients with bacterial vaginosis |

| Lead author(s) |

Marguerite A. Urban, MD; Maria Teresa Timoney, CNM, NP, MS, RN |

| Writing group |

Rona M. Vail, MD, AAHIVS; Sanjiv S. Shah, MD, MPH, AAHIVS; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Samuel T. Merrick, MD, FIDSA; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD, FACP, AAHIVS; Anne K. Monroe, MD, MSPH; Jessica Rodrigues, MPH, MS; Brianna L. Norton, DO, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH, MSc, FACP |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures. |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

| Related NYSDOH AI resources |

GuidelineGuidancePodcast |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on February 19, 2026