Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: July 23, 2024

Lead authors: Christine Kerr, MD; Mary Dyer, MD

Writing group: Rona M. Vail, MD, AAHIVS; Sanjiv S. Shah, MD, MPH, AAHIVM, AAHIV; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD, FACP, AAHIVS; Anne K. Monroe, MD, MSPH; Jessica Rodrigues, MPH, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Brianna L. Norton, DO, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: February 9, 2021

This guideline on primary care for adults with HIV was developed by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) to guide clinicians in New York State who provide primary care for adults (aged ≥18 years) with HIV. The goals of the guideline include:

- Increasing access to comprehensive primary care in their setting of choice for adults with HIV in New York State.

- Clarifying that primary care for adults is generally the same for adults with and without HIV, while also clarifying medical care needs particular to adults with HIV.

- Providing effective tools for all clinicians delivering comprehensive primary care to adults with HIV, including family practice clinicians, internists, and HIV or infectious diseases specialists.

At the end of 2021, there were an estimated 1.2 million individuals age ≥13 years with HIV in the United States, and of the 32,100 newly diagnosed infections that same year, 3,000 were among people aged ≥55 years CDC 2024. As of December 2022, there were an estimated 104,124 individuals with HIV in New York State, 75% of whom were aged ≥40 years and 57% of whom were aged ≥50 years NYSDOH 2023. Advances in antiretroviral therapy (ART) over the past 2 decades have significantly improved lifespan Gueler, et al. 2017; Samji, et al. 2013; Zwahlen, et al. 2009: life expectancy for a patient newly diagnosed with HIV now approaches that of an individual without a diagnosis of HIV. ART lowers rates of opportunistic infections and mortality Lundgren, et al. 2015; El-Sadr, et al. 2006, and the immune system reconstitution observed with the use of ART is associated with significantly improved health outcomes in patients with HIV Marin, et al. 2009; Emery, et al. 2008. Clinicians should start and maintain ART in all patients with HIV.

Structure and use of this guideline: With the assumption that clinicians are familiar with performing a comprehensive patient history, examination, and review of systems, the authors focus on aspects of primary care that require additional attention in patients with HIV.

Note on “experienced” and “expert” HIV care providers: Throughout this guideline, when reference is made to “experienced HIV care provider” or “expert HIV care provider,” those terms are referring to the following 2017 NYSDOH AI definitions:

- Experienced HIV care provider: Practitioners who have been accorded HIV Experienced Provider status by the American Academy of HIV Medicine or have met the HIV Medicine Association’s definition of an experienced provider are eligible for designation as an HIV Experienced Provider in New York State. Nurse practitioners and licensed midwives who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV in collaboration with a physician may be considered HIV Experienced Providers as long as all other practice agreements are met (8 NYCRR 79-5:1; 10 NYCRR 85.36; 8 NYCRR 139-6900). Physician assistants who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV under the supervision of an HIV Specialist physician may also be considered HIV Experienced Providers (10 NYCRR 94.2)

- Expert HIV care provider: A provider with extensive experience in the management of complex patients with HIV.

Patient-Centered Care

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Approach to Care

Opportunistic Infection Prophylaxis

|

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; OI, opportunistic infection. |

Ideally, access to primary and HIV-related general medical care should be available to adults with HIV in a setting that minimizes barriers to care and allows patients to maintain a relationship with their preferred healthcare provider. The 4 flowcharts below can be applied to adult primary care in any setting to ensure that patients with HIV receive ART and appropriate monitoring based on their HIV and ART status, age, and identified health risks. The 4 flowcharts offer guidance for care providers with or without previous HIV care experience; working in any outpatient setting; and managing the care of new patients with a confirmed or unconfirmed HIV diagnosis, established patients in need of routine annual care and monitoring, or patients aging with HIV, which is discussed in the NYSDOH AI Guidance: Addressing the Needs of Older Patients in HIV Care.

- Flowchart 1 steps through a first visit with a new patient with a new HIV diagnosis and prioritizes confirmation of the HIV diagnosis and ART initiation.

- Flowchart 2 describes a first visit with a new patient who has a confirmed HIV diagnosis and is taking ART. After establishing whether an ART switch is needed, attention is focused on standard primary care, with HIV-specific additions, such as HIV history.

- Flowchart 3 walks through a first visit with a new patient with a confirmed HIV diagnosis who is not taking ART either because it has not been initiated or because the patient stopped taking antiretroviral medications.

- Flowchart 4 illustrates a routine visit, “sick patient” visit, and a post-hospitalization visit with an established patient.

All 4 flowcharts address history-taking, assessment, laboratory testing, screening and preventive care, counseling, and follow-up with links to checklists, other guidelines, and multiple resources. Each flowchart also addresses risk reduction.

Flowchart 1: Initial Visit: New Patient, New HIV Diagnosis, NOT Taking ART

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CM, cryptococcal meningitis; CMV, cytomegalovirus; doxy-PEP, doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; OI, opportunistic infection; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PJP, pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; ROS, review of systems; STI, sexually transmitted infection; SUD, substance use disorder; TB, tuberculosis; U=U, undetectable=untransmittable.

Notes:

- Ongoing discussion and education regarding HIV disclosure, U=U, PrEP and PEP for sex partners, and harm reduction is recommended.

- Ongoing surveillance for diseases transmitted through the same routes as HIV, including HCV, HBV, HPV, and other STIs, is recommended.

Download flowchart: Initial Visit: New Patient, New HIV Diagnosis, NOT Taking ART

Flowchart 2: Initial Visit: New Patient, HIV Confirmed, IS Taking ART

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CM, cryptococcal meningitis; CMV, cytomegalovirus; doxy-PEP, doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; OI, opportunistic infection; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PJP, pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; ROS, review of systems; STI, sexually transmitted infection; SUD, substance use disorder; TB, tuberculosis; U=U, undetectable=untransmittable.

Notes:

- Monitor for potential long-term effects of HIV and ART (e.g., bone density changes, dyslipidemia, weight gain, and renal dysfunction) and for comorbidities that occur more often and at younger ages in people with HIV, including atherosclerotic heart disease, non-HIV-related malignancies, renal disease, liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, neurocognitive dysfunction, depression, and frailty.

- Recent studies have found that smoking and hypertension contribute significantly to morbidity, regardless of HIV-related risk factors such as CD4 cell count or viral load Althoff, et al. 2019.

- Ongoing discussion and patient education regarding HIV disclosure, principles of U=U, PrEP and PEP for sex partners, and harm reduction is recommended.

- Ongoing surveillance for diseases transmitted through the same routes as HIV, including HCV, HBV, HPV, and other STIs, is recommended.

Download flowchart: Initial Visit: New Patient, HIV Confirmed, IS Taking ART

Flowchart 3: Initial Visit: New Patient, HIV Confirmed, NOT Taking ART

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; ARV, antiretroviral; CM, cryptococcal meningitis; CMP, comprehensive metabolic panel; CMV, cytomegalovirus; doxy-PEP, doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; OI, opportunistic infection; PEP, post-exposure prophylaxis; PJP, pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; RAM, resistance-associated mutation; ROS, review of systems; STI, sexually transmitted infection; SUD, substance use disorder; TB, tuberculosis; U=U, undetectable=untransmittable.

Notes:

- Monitor for potential long-term effects of HIV and ART (e.g., bone density changes, dyslipidemia, weight gain, and renal dysfunction) and comorbidities.

- Smoking and hypertension contribute significantly to morbidity, regardless of HIV-related risk factors such as CD4 cell count or viral load Althoff, et al. 2019.

- Ongoing discussion and patient education regarding HIV disclosure, principles of U=U, PrEP and PEP for sex partners, and harm reduction is recommended.

- Ongoing surveillance for diseases transmitted through the same routes as HIV, including HCV, HBV, HPV, and other STIs, is recommended.

Download flowchart: Initial Visit: New Patient, HIV Confirmed, NOT Taking ART

Flowchart 4: Annual, Routine, New Illness, or Post-Hospitalization Visit: Established Patient Who IS Taking ART

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; doxy-PEP, doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HPV, human papillomavirus; ROS, review of systems; STI, sexually transmitted infection; SUD, substance use disorder; U=U, undetectable = untransmittable.

Notes:

- Monitor for potential long-term effects of HIV and ART (e.g., bone density changes, dyslipidemia, weight gain, and renal dysfunction) and for comorbidities that occur more often and at younger ages in people with HIV, including atherosclerotic heart disease, non-HIV-related malignancies, renal disease, liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, neurocognitive dysfunction, depression, and frailty.

- Smoking and hypertension contribute significantly to morbidity, regardless of HIV-related risk factors such as CD4 cell count or viral load Althoff, et al. 2019.

- Ongoing surveillance for diseases transmitted through the same routes as HIV, including HCV, HBV, HPV, and other STIs, is recommended.

Goals of Primary Care for Adults With HIV

The standard approach to primary care is the same for patients with and without HIV, whether care is delivered by a specialist or generalist. In addition to mainstays of primary care, there are unique considerations for patients with HIV, including treatment of HIV itself. Clinicians should inform patients of the benefits of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and strongly encourage patients to initiate ART as soon as possible (for evidence-based recommendations, see the NYSDOH AI guideline Rapid ART Initiation).

Health Maintenance

Regardless of HIV treatment, however, when compared with individuals without HIV, the risk of many comorbidities, including metabolic and infectious diseases and cancers, is higher in people with HIV (see Box 1, below). In one study, patients with HIV had significantly fewer morbidity-free years than patients without HIV Marcus, et al. 2020.

The increased incidence of comorbid conditions is associated with several factors, some of which are HIV disease-specific, such as ongoing immune activation-associated risks Deeks, et al. 2015; Deeks 2011; presumed medication-associated toxicities, such as accelerated bone density loss; duration of HIV viremia Lang, et al. 2012; and others, including increased rates of malignancy and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Many of these conditions occur regardless of immune reconstitution and HIV disease stage, and long-term HIV survivors may face the burdens of concomitant disease, medication-associated toxicity (particularly for those on or with prolonged exposure to early antiretroviral medications), and advanced aging Maggi, et al. 2019.

Regardless of viral suppression or CD4 count, HIV infection is associated with an increased risk of comorbidities related to persistent inflammation associated with the virus itself. ART reduces morbidity and mortality but can also contribute to comorbidities, such as weight gain Bourgi(a), et al. 2020; Bourgi(b), et al. 2020 and osteoporosis Komatsu, et al. 2018; Grigsby, et al. 2010.

Immune function: Morbidity and mortality are increased in individuals with low CD4 cell counts Castilho, et al. 2022; Althoff, et al. 2019; May, et al. 2016, and the risk is greater in patients with unintentional weight loss or poor functional status Siika, et al. 2018; Serrano-Villar, et al. 2014. Some conditions, such as AIDS-defining malignancies, are more common in individuals with low CD4 cell counts and may be associated with markedly poor outcomes Borges, et al. 2014. See the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents With HIV.

Conditions related to low nadir CD4 cell count: A low nadir CD4 cell count (lowest lifetime CD4 cell count) reflects severe pretreatment immune dysfunction. Immune recovery in patients with low nadir CD4 cell counts may take longer or be less complete than in those with higher nadir CD4 cell counts Stirrup, et al. 2018; Collazos, et al. 2016. Studies have found increased morbidity and mortality for 5 years after ART is initiated May, et al. 2016, and nadir CD4 cell count is a predictor of cognitive impairment and disorders Ellis, et al. 2011. Some patients may have persistently low CD4 cell counts despite achieving viral load suppression and will be at increased risk of clinical progression to AIDS-related and non-AIDS-related illnesses and death Baker, et al. 2008.

HIV-specific components of care: Additional essential components of primary care for patients with HIV include:

- Patient education and encouragement regarding adherence to ART to maintain viral suppression

- Opportunistic infection prophylaxis

- Immunizations (note recommendations specific to adults with HIV, which may differ from those for adults without HIV)

- Monitoring for potential long-term effects of HIV and ART, such as bone density changes, dyslipidemia, weight gain, renal dysfunction, and impaired cognitive functioning

- Identification and management of comorbidities that occur more often and at younger ages in people with HIV, including atherosclerotic heart disease, non-HIV-related malignancies, renal disease, liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, neurocognitive dysfunction, depression, and frailty (see Box 1, above). Recent studies have found that smoking and hypertension contribute significantly to morbidity, regardless of HIV-related risk factors, such as CD4 cell count or viral load Althoff, et al. 2019.

- Ongoing surveillance for diseases transmitted through the same routes as HIV, including HCV, hepatitis B virus, human papillomavirus, and other sexually transmitted infections

- Screening and treatment for substance use, including tobacco use

- Ongoing discussion and patient education regarding disclosure of HIV status, principles of U=U (undetectable = untransmittable), pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis for sex partners, and harm reduction strategies

Improving Access to Care

Health equity: Improving access to care within communities and facilitating access through primary care providers can be a solution to significant healthcare disparities among people living with HIV. Addressing health inequities through interventions such as culturally appropriate counseling, peer support, motivational interviewing, and cognitive behavioral therapy in the healthcare setting can lead to improved adherence and outcomes Bogart, et al. 2023; Bogart, et al. 2021. Though more research is needed, it appears that healthcare workers who recognize and address their implicit biases may reduce gaps in care. In addition, diversification of the healthcare workforce and attention to social determinants of health may reduce inequities.

Stigma and medical mistrust: Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence, which can affect disease outcomes Kalichman, et al. 2020; Kemp, et al. 2019; Turan, et al. 2017. Studies have found that both internalized stigma (manifested in feelings about self) and externalized stigma (enacted by others) can influence how often a patient seeks care, their engagement in care, and whether they maintain viral load suppression. Successful interventions to reduce stigma and medical mistrust include education of healthcare providers Geter, et al. 2018, peer support Flórez, et al. 2017, and social support Rao, et al. 2018.

Consent and confidentiality: A patient’s past medical records should be obtained whenever possible. Any HIV-related patient information is confidential, and by law, care providers must maintain this confidentiality (see New York Codes, Rules, and Regulations: Part 63–HIV/AIDS Testing, Reporting and Confidentiality of HIV-Related Information).

Sharing of patient medical records among care providers who participate in health information exchanges such as the Statewide Health Information Network for New York (SHIN-NY), can facilitate information exchange (see New York eHealth Collaborative > What is the SHIN-NY?). Patients must sign a standard medical record request form (see the New York State standard consent form). Information related to HIV care can be exchanged among care providers only if a patient consents specifically to the release of HIV/AIDS-related information on the standard form.

Trauma-informed care: A trauma-informed approach to care can help mitigate the effects of past medical trauma, such as frightening experiences or stigma associated with HIV Tang, et al. 2020; Sherr, et al. 2011 and can facilitate improved outcomes Brown, et al. 2024; Sikkema, et al. 2018. See the following for more information:

- New York State Office of Mental Health: Recovery From Trauma

- New York State Trauma-Informed Network & Resource Center

- Trauma Informed Care in Medicine: Current Knowledge and Future Research Directions (article) Raja, et al. 2015

Case management: The goal of comprehensive case management is to improve patient outcomes and retention in care by providing the support and resources of a healthcare team that includes the clinical care provider. Comprehensive case management connects patients to community resources and can improve engagement with medical care, including screening and management of comorbid conditions, and HIV-specific outcomes, such as immune reconstitution and viral load suppression [López, et al. 2018; Brennan-Ing, et al. 2016].

Case management can dramatically improve viral load suppression among individuals who inject drugs or smoke crack cocaine, 2 groups that are difficult to retain in care: one study demonstrated an increase in viral load suppression from 32% to 74% and another found a mortality benefit from case management intervention Kral, et al. 2018; Miller, et al. 2018. For patients estranged from care, case management can facilitate effective re-engagement Irvine, et al. 2021; Shacham, et al. 2018.

Peer support: Peer support from someone with shared life experience can provide emotional and practical guidance and help reduce stigma. Peer support has been found to improve retention in care Cabral, et al. 2018 and viral suppression, including among recently incarcerated individuals Feldman, et al. 2023; Cunningham, et al. 2018. The positive effect was most pronounced when patients had a high level of trust in the organization providing peer services, such as the places where they already receive care Sokol and Fisher 2016.

HIV-Specific Primary Care

In the primary care setting, HIV management is similar to other chronic disease management, and comorbidity screening and management are standard, as in primary care for people who do not have HIV. Included below are practical recommendations and guidance for the initial visit and ongoing clinical care of individuals with HIV, with links to other evidence-based guidelines where appropriate.

History-Taking

History-taking for patients with HIV requires attention to all of the elements standard in primary care and several additional elements detailed in Checklist 1: HIV-Specific Elements of Health Status and History, below. Identifying, assessing, and monitoring HIV- and antiretroviral therapy (ART)-related complications and other HIV-specific comorbidities is essential. A comprehensive baseline history includes sexual health, mental health, substance use (including illicit use of prescription drugs), and social history. Patients may choose not to disclose all pertinent personal information during the first visit, but a sympathetic and nonjudgmental attitude can help establish trust and facilitate further discussion and disclosure during subsequent visits.

HIV history: Essential components of an HIV-specific medical history are detailed below and in Checklist 1: HIV-Specific Elements of Health Status and History. Confirmation of a patient’s HIV infection should include documented laboratory testing results. If results are not available, baseline testing should be performed as noted in Checklist 2: Initial (Baseline) and Annual Laboratory Testing for Adults With HIV, below (also see the NYSDOH AI guideline HIV Testing > HIV Testing With the Standard 3-Step Algorithm). If a patient was recently diagnosed with HIV, a discussion of the reasons for testing and the route of exposure will assist the clinician in identifying appropriate goals for risk reduction education, counseling, and intervention that may include ongoing screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs).

Essential components of an HIV-specific medical history (see Checklist 1, below):

- Viral load and CD4 cell count at diagnosis, if known

- Patient circumstances at the time of diagnosis (housing, employment, food security, relationship status, travel history, pets, etc.)

- ART history, including previous regimens, reasons for any changes in prior regimens, and any adverse effects

- Pauses in ART and lapses in adherence

- Previous resistance testing results

- History of opportunistic infections (OIs)

- Immunization history

- History of HIV-related hospitalization(s)

- Disclosure status (whether partners, family, or friends are aware of HIV status) and partner notification

- History of other STIs with shared risk factors, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), and human papillomavirus (HPV)

- Ongoing high-risk behaviors for transmission of HIV and acquisition of STIs or infections associated with injection drug use

- Experience of stigma and social support

ART history: An ART history includes all previous antiretroviral medications, adherence, and dates of and reasons for discontinuation (e.g., allergies, adverse effects, pill-taking fatigue or discomfort, and drug resistance). Understanding the reasons and, when possible, simplifying ART regimens or reducing pill burden will support a therapeutic alliance that may facilitate adherence going forward.

ART initiation: If a patient with HIV has not yet started ART, it should be initiated as soon as appropriate and possible, and any barriers to ART initiation should be assessed so support can be provided. For evidence-based recommendations, see the NYSDOH AI guideline Rapid ART Initiation.

Adherence: For patients already taking ART, assessing and supporting optimal adherence are crucial and may include careful evaluation of adverse medication effects that often interfere with adherence or result in medication cessation. Other factors to discuss that may pose barriers to adherence include insurance coverage, housing instability, disclosure status, substance use, and mental health. A discussion about adherence can prompt regimen simplification, such as a switch to a single-tablet regimen or a referral to case management or peer support, and it can alert the clinical team to other barriers to effective care, especially among patients at higher risk of adherence challenges Altice, et al. 2019; Bazzi, et al. 2019; Shah, et al. 2019.

Metabolic changes: Weight gain can be expected when initiating ART and is often attributed to a “return to health” with improved immune function. However, ART itself has been associated with metabolic changes. Integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs), including dolutegravir, bictegravir, raltegravir, elvitegravir, and cabotegravir, have been implicated in modest weight gain that reaches a plateau after 2 years of therapy Kileel, et al. 2023. Despite the weight gain associated with INSTI treatment, 2 studies found no difference in short- or long-term risk of cardiovascular disease events among treatment-naive participants who started INSTI-based ART compared with other ART Surial, et al. 2023; Neesgaard, et al. 2022. Protease inhibitors are known to alter lipids unfavorably and can lead to lipodystrophy, a condition characterized by abdominal fat accumulation with peripheral lipoatrophy, insulin resistance, and hyperlipidemia Waters, et al. 2023.

Switching from tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) to tenofovir alafenamide (TAF) is a common strategy to protect against adverse renal and bone effects, but a change from TDF to TAF has been associated with a significant increase in triglyceride, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol levels, but no significant changes in LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol/HDL ratio. However, a switch from TDF‑ to TAF-based therapy has been associated with an increased calculated cardiovascular risk. And in a large, diverse U.S. cohort of people with HIV, a switch from TDF to TAF was associated with pronounced weight gain immediately after the switch, regardless of the core ART class or core agent, suggesting an independent effect of TAF on weight gain Mallon, et al. 2021; Plum, et al. 2021; Surial, et al. 2021. Unintentional weight loss may prompt investigation of malignancy, infection, endocrine disorder, or psychosocial instability.

Viral hepatitis status: Many of the risk factors for acquisition of viral hepatitis are the same as those for HIV. Assessment of a patient’s viral hepatitis status, including a history of viral hepatitis infection and treatment, helps clinicians determine optimal treatment options. In individuals with HIV, the progression of HBV- or HCV-associated liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, cancer, portal hypertension, and encephalopathy is more rapid than in those without HIV Sherman and Thomas 2022; Kim, et al. 2021; Sun, et al. 2021; Mocroft, et al. 2020; Klein, et al. 2016.

HCV: Because the risk of severe liver disease is increased in patients with HIV Soti, et al. 2018; Klein, et al. 2016, all patients with HCV and HIV should be treated for HCV infection as soon as possible (see Table 2: Interpretation of HBV Screening Test Results and Table 3: Interpretation of HCV Test Results, below). Potential interactions between ART and HCV medications should be identified and addressed. Treatment of chronic HCV is the same for individuals with and without HIV Sherman and Thomas 2022.

HBV: A history of HBV infection will influence HIV medication choice and requires attention to drug-drug interactions. Because tenofovir, emtricitabine, and lamivudine are effective against both HBV and HIV, assessment of baseline HBV status informs the choice of ART regimen that will treat HBV and HIV coinfection. However, ART initiation should not be delayed pending evaluation of HBV status, fibrosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; doxy-PEP, doxycycline post-exposure prophylaxis; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; OI, opportunistic infection; OTC, over-the-counter; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; STIs, sexually transmitted infections; USPSTF, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. |

| Checklist 1: HIV-Specific Elements of Health Status and History |

| Note: The items listed below are in addition to routine primary care assessment. The standard approach to primary care is the same for patients with and without HIV, whether care is delivered by a specialist or internist; however, there are unique considerations for patients with HIV, including treatment of HIV itself.

HIV history: Diagnosis date and source; ART regimens, prior PrEP use, challenges, adverse effects, pauses, and lapses; previous resistance testing results; HIV-related hospitalizations; disclosure status; history of OIs, including prophylaxis and treatment; history of AIDS-defining conditions and treatments; signs or symptoms of potential long-term effects of ART (e.g., bone density changes, dyslipidemia, weight gain, renal dysfunction).

Medications: Experienced and potential ART drug-drug interactions with any of the patient’s current medications (prescribed, OTC, herbal and nonpharmacologic agents); hormone use, including nonprescription, route of administration, and source. Immunizations: Status of immunizations recommended for adults with HIV; travel-related immunization status if indicated. Sexually transmitted infections: History and treatment of syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia, human papillomavirus, and other STIs; history of HIV transmission and ongoing risk factors; current and past experience with prevention, including doxy-PEP. Hepatic: History of and treatment for viral hepatitis (HAV, HBV, HCV); history of cirrhosis (compensated/decompensated) or previous hepatic compromise. Neurologic: Cognitive and neurobehavioral function; history of ischemia or thrombosis; history or symptoms of neuropathy, including symmetric distal polyneuropathy (common, particularly in patients exposed to earlier generations of ART). Endocrine: History of weight gain or loss; osteoporosis; lipodystrophy; symptoms of testosterone deficiency. Nutritional status and food security: Current dietary habits, appetite, and food security; history of malnutrition, vitamin deficiencies (particularly vitamin D and calcium), wasting, and disordered eating. Gender: Patient’s gender identity; history or plans for gender transition; gender-affirming hormone use, including source; gender-affirming surgical history; sex organ inventory (presence or absence of a penis, testes, prostate, breasts, vagina, cervix, uterus, and ovaries; patient’s preferred terms for body parts). Renal: Risk for HIV-associated nephropathy and potentially complicating diagnoses (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, other causes of chronic kidney disease). Consider ART history. Behavioral health: Screen for anxiety or suicide risk with new diagnosis; assess potential effect on adherence with untreated behavioral health diagnosis.

Substance use (alcohol, nonprescribed drugs, prescribed drug misuse, tobacco): History and current use; use of substances with sex; harm reduction; ongoing high-risk behaviors for transmission of HIV and acquisition of STIs or infections associated with injection drug use.

Sexual health: Sexual identity; current and past sex partner(s); HIV, ART, viral load, and PrEP status of sex partner(s); frequency and preferred sexual activities (to assess risk); history of sexual dysfunction or other challenges.

Financial health: Current financial and employment status; access to resources if needed; healthcare coverage (including medical, hospitalization, mental health, prescriptions, and dental care) or access to resources for uninsured people; current or history of engagement in transactional sex. Assess for urgent needs. Functional status: Ability to perform activities of daily living; mobility; transportation; independence at home or in the community. Assess for urgent needs. Relationships, responsibilities, and support: Patient-defined family and significant relationships, including dependents; primary social network; people who know the patient has HIV; long-term care plans. Assess for urgent needs. Social determinants of health: Housing status and stability, food security, transportation, utilities, child care, employment, education, finances, personal safety, neighborhood safety, social support, criminal justice engagement, etc. Trauma, stress, and stigma: History of trauma, including medical and witnessed trauma; current and past experience with domestic, physical, emotional, verbal, and intimate partner violence; history or current experience with elder abuse; current major stressors; management and coping skills; experience with HIV-associated or other stigmas. Assess for urgent needs. |

Download Checklist 1: HIV-Specific Elements of Health Status and History Printable PDF

Immunizations

Recommended immunizations for adults with HIV are available in the NYSDOH AI guideline Immunizations for Adults With HIV and include the following:

General Medical Status and Physical Examination

This guideline assumes that care providers are familiar with performing a comprehensive physical examination. Particular attention may be needed to potential complications of immune suppression in patients with unsuppressed HIV and low CD4 cell counts.

Medications: Ideally, a complete medication history should be acquired at baseline and updated as needed during future visits. A detailed medication history (with emphasis on ART) allows the clinician to identify possible adverse drug-drug interactions between antiretroviral and other medications the patient may be taking for treatment of comorbidities. Patients with HIV may have multiple comorbidities due to infection and related inflammatory processes or the effects of medications.

Examination of a patient’s current medical status and medication regimen may identify the need for changes in the ART regimen, changes in medications prescribed for other medical conditions, options for simplification of medication regimens, and medications that may be discontinued; see the NYSDOH AI guideline Selecting an Initial ART Regimen > Special Considerations for Comorbid Conditions.

The following resources are available for checking drug-drug interactions:

- NYSDOH AI Resource: ART Drug-Drug Interactions

- Northeast/Caribbean AETC: HIV and HCV Drug Interactions: Quick Guides for Clinicians

- University of Liverpool: HIV Drug Interaction Checker

Head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat: An ophthalmologic examination at baseline and at least annually thereafter is indicated for patients with a CD4 count <50 cells/mm3. Infections, including cytomegalovirus (CMV), varicella-zoster virus, herpesvirus, and syphilis can lead to retinitis, retinal necrosis, and vision loss Nakamoto, et al. 2004. Before the introduction of highly active ART, the 10-year cumulative incidence of CMV retinitis was 33.6% for individuals with CD4 counts <50 cells/mm3 and 4.2% for those with CD4 counts <200 cells/mm3. While incidence has decreased significantly, it is still important to consider, particularly in patients with significant immunocompromise, i.e., with CD4 count <50 cells/mm3 Sugar, et al. 2012. In patients taking atazanavir as part of their ART regimen, icterus may be present by causing a benign hyperbilirubinemia Bertz, et al. 2013. HIV viremia can also lead to a direct retinopathy at high viral loads and low CD4 cell counts Jabs 1995.

Although HIV infection itself does not increase the likelihood of viral upper respiratory infections, symptoms such as cough, sinusitis, and otitis are common in patients with HIV Brown, et al. 2017; Chiarella and Grammer 2017; Small and Rosenstreich 1997. Because sinusitis and otitis can present without significant facial pain or discomfort in patients with CD4 counts <50 cells/mm3, it is reasonable to perform imaging and evaluate for infection with atypical organisms, such as fungal sinusitis, more readily in these patients.

People with HIV also have a higher risk of oral malignancies than those without HIV, and those with low CD4 cell counts may have diverse oropharyngeal findings, including oral Kaposi sarcoma, oral candidiasis, human papillomavirus (HPV)- and HIV-related parotitis, and necrotizing gingivitis, requiring evaluation during in-person examinations Trevillyan, et al. 2018; Sorensen 2011; Epstein 2007. Clinicians should encourage patients to have annual dental examinations (see National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research: HIV/AIDS & Oral Health and NYSDOH AI guideline Management of Periodontal Disease).

Cardiovascular: People with HIV are at higher risk for coronary artery and cardiovascular disease and may develop disease earlier than those without HIV; this includes a risk of myocardial infarction more than twice that for those without HIV Shah, et al. 2018; Freiberg, et al. 2013. The CVD-associated mortality risk is increasing as well, especially as a proportion of overall mortality in those with HIV Feinstein, et al. 2016. CVD risk assessment is crucial, but standard risk calculators may underestimate the risk in people with HIV, particularly in Black people and cisgender women Grinspoon, et al. 2024. Shared decision-making may be necessary to compensate for underestimated risk when deciding whether to use statins or implement lifestyle changes. Pitavastatin has been shown to significantly reduce cardiovascular risk even in those not considered to be at high risk based on risk calculators Grinspoon, et al. 2023. Also see U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS): Guidelines for the Use of Antiviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents With HIV > Recommendations for the Use of Statin Therapy as Primary Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in People with HIV.

Respiratory: Clinicians should perform a lung examination at baseline and at least annually, or more often if indicated. Chronic lung disease, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, is increasingly common among older people with HIV, among smokers, and among those who have had Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (PJP; formerly known as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia or PCP), who may have residual blebs that can lead to pneumothorax Risso, et al. 2017.

In patients with low CD4 cell counts who have respiratory examination findings or symptoms, clinicians should perform a chest X-ray or computerized tomography to evaluate for infection or neoplasm Yee, et al. 2020. Clinicians should also maintain a low threshold for suspicion of tuberculosis (TB) and pursue appropriate diagnostic and public health measures if TB is suspected.

Hematologic/lymphatic: Lymphadenopathy may occur at any stage of HIV disease, does not always correlate with disease progression or prognosis, and may be less pronounced in older patients. However, widespread, firm, or asymmetrical lymphadenopathy requires prompt consideration of lymphoma, syphilis, TB, mycobacterium avium-intracellulare infection, and lymphogranuloma venereum, all of which can occur regardless of CD4 cell count but are more likely at lower CD4 cell counts. Nonadherence to ART may also be considered.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and primary central nervous system lymphoma are AIDS-defining conditions; lymphoproliferative diseases, such as Castleman disease, should be considered as well. Any evidence of lymph nodes larger than 1 cm or evidence of fixed, matted, or hard nodes should prompt consideration for biopsy, particularly if a patient has a low CD4 cell count.

Dermatologic: An annual comprehensive skin examination ensures that concerns are identified early. Regardless of CD4 cell count, findings such as shingles and psoriasis are more frequent in people with HIV than in those without Alpalhão, et al. 2019; Erdmann, et al. 2018. For more information, see National HIV Curriculum: Cutaneous Manifestations.

Attention should be paid to any dermatologic history, such as a history of skin cancers and recurrent rash, that could be consistent with psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, eosinophilic folliculitis, or secondary syphilis Alpalhão, et al. 2019; Green, et al. 1996. Symptoms can overlap and coexist.

Less common diseases, such as Kaposi sarcoma, eosinophilic folliculitis, disseminated zoster, molluscum contagiosum, and cutaneous HPV, may occur in patients with low CD4 cell counts. Familiarity with these diseases is important.

Neurologic: As noted in Checklist 1: HIV-Specific Elements of Health Status and History, above, clinicians should examine patients’ neurologic and cognitive function at baseline, at least annually for those at risk (due to low CD4 cell count, age, or comorbidities), and more often if there are patient or family concerns. Several standardized tests are available, including the MoCA Test, Mini-Cog, and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

Compared with patients who have higher CD4 cell counts, patients with low CD4 cell counts may be at increased risk of rare neurologic conditions (e.g., progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, HIV-associated neurologic disease, toxoplasmosis, and cryptococcal meningitis) and common conditions with atypical presentation, such as syphilis and TB.

Imaging and diagnostic workups are warranted for new or persistent neurologic symptoms (e.g., seizure, changes in mental status, or persistent headache) regardless of CD4 cell count, but especially in patients with a low CD4 cell count.

Comorbidities: For patients with comorbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, lung disease, renal disease, diabetes mellitus, and malignancies, personal and family history should be obtained and individual risk factors assessed. Because HIV has been associated with increased risk and accelerated disease process for many comorbidities, care providers should be sure to discuss appropriate screening and have a low threshold for diagnostic testing referral if symptoms develop Kaspar and Sterling 2017; Triant 2013; Islam, et al. 2012; Shiels, et al. 2011; Bower, et al. 2009; Crothers, et al. 2006. In individuals taking ART, risk factors such as smoking and hypertension cause more morbidity and mortality than HIV-specific risk factors such as low CD4 cell count Althoff, et al. 2019; Trickey, et al. 2016; Helleberg, et al. 2015.

History of particular comorbidities may also influence medication choice for patients starting ART. For example, patients with a history of metabolic disease may wish to avoid protease inhibitors, which are associated with central obesity, and patients with risk factors for significant renal disease may wish to avoid TDF. More frequent adverse effect monitoring may be warranted for patients taking ART or other medications that can affect these conditions Crum-Cianflone, et al. 2010. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is observed in 30% to 40% of people with HIV Kaspar and Sterling 2017 and may affect both monitoring and medication choice.

Endocrine conditions, such as metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, lipodystrophy, and osteoporosis, may be worsened by certain antiretroviral medications. A full medication history will help clinicians identify the possibility of ART-associated exacerbation of these conditions Noubissi, et al. 2018; Gazzaruso, et al. 2003. Because thyroid disease and hypogonadism occur more often in people with HIV than in those without, a low threshold for screening is appropriate.

Functional status and aging: As the population living with HIV ages, frailty, functional, and cognitive assessments are essential. Baseline discussion of memory loss, neuropathic symptoms, and chronic pain can help identify conditions that may affect ART adherence. Nadir CD4 cell count is a predictor of cognitive impairment and disorders Ellis, et al. 2011. Collecting structured data through the use of standardized assessments will help clinicians to determine illness course; standardized assessment tools include the MoCA Test, Mini-Cog, and MMSE. An annual assessment of functional status is also indicated. For more information, see the NYSDOH AI Guidance: Addressing the Needs of Older Patients in HIV Care.

Psychosocial status: Baseline and annual psychosocial assessments include a detailed sexual, trauma, substance use, and psychiatric history; more frequent assessment may be required for patients who require follow-up in any area. Care providers, particularly those new to HIV care, may initially feel uncomfortable conducting these assessments. Resources are provided below for structured assessments. When possible, a team approach may be helpful and allow for the incorporation of multidisciplinary assessments, including those of a case manager and clinical social worker.

Sexual health: Discussion of sexual health, including a patient’s STI history at baseline and annually, provides an opportunity to identify a patient’s concerns, questions, and knowledge of harm reduction. The frequency of the sexual health assessment is based on risk factors. Use of nonjudgmental, sex-positive language in any discussion of sexual health can facilitate open discussion and therapeutic alliance. Discussion of U=U (undetectable = untransmittable) in the clinical setting may reduce stigma and facilitate discussion of important considerations in sexual health. See the NYSDOH AI Guidance: Adopting a Patient-Centered Approach to Sexual Health and GOALS Framework for Sexual History-Taking in Primary Care.

Reproductive status: Ascertainment of a patient’s reproductive history and goals, including plans for conception in patients of childbearing potential, can facilitate discussion of contraception needs and current strategies to eliminate perinatal HIV transmission. The risk of perinatal transmission is less than 1% when patients are virally suppressed Ioannidis, et al. 2001. For patients who are pregnant or planning pregnancy, care providers should discuss appropriate preconception planning, including folate use, medication safety, and plans for breastfeeding, as well as the risk to a partner without HIV if the patient has a detectable viral load. Provide education about HIV post- and pre-exposure prophylaxis as appropriate.

Menopause, whether natural or surgical, has been associated with increased fatigue and muscle aches or pains in people with HIV Schnall, et al. 2018.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Testing

| Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; Ag, antigen; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; c, core; CBC, complete blood count; CMP, comprehensive metabolic panel; CMV, cytomegalovirus; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IgG, immunoglobulin; IGRA, interferon-gamma release assay; MSM, men who have sex with men; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PPD, purified protein derivative; s, surface; TB, tuberculosis; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

Notes:

|

|

| Checklist 2: Initial (Baseline) and Annual Laboratory Testing for Adults With HIV Also see clinical comments in Table 1: Clinical Comments on Recommended Laboratory Testing for Adults With HIV |

|

Initial AND Annual Testing

|

Initial Testing Only (unless otherwise indicated):

If Clinically Appropriate (i.e., the patient is symptomatic or has a CD4 count <200 cells/mm3):

|

Table 1, below, provides additional clinical information to supplement the checklist above.

| Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; Ag, antigen; ART, antiretroviral therapy; CBC, complete blood count; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DHHS, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IGRA, interferon-gamma release assay; INSTI, integrase strand transfer inhibitor; MSM, men who have sex with men; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PI, protease inhibitor; PPD, purified protein derivative; s, surface; STI, sexually transmitted infection; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TB, tuberculosis; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; UTI, urinary tract infection; ZDV, zidovudine. | |

| Table 1: Clinical Comments on Recommended Laboratory Testing for Adults With HIV | |

| Laboratory Test | Comments |

| HIV-1 RNA quantitative viral load |

|

| CD4 lymphocyte count |

|

| HIV-1 resistance testing (genotypic) |

|

| G6PD |

|

| CBC |

|

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate |

|

| Hepatic panel |

|

| Random blood glucose (fasting or hemoglobin A1C if high) |

|

| TB screening |

|

| HAV |

|

| HBV |

|

| HCV |

|

| Measles titer | Vaccinate if the patient is not immune and has a CD4 count >200 cells/mm3. |

| Varicella titer |

|

| Urinalysis |

|

| Urine pregnancy test |

|

| Lipid panel |

|

| Serum TSH |

|

| Gonorrhea and chlamydia |

|

| Syphilis |

|

| Trichomonas | Perform screening test if the patient has a vagina and is sexually active. |

| HLA-B*5701 | Must be performed before initiation of abacavir, otherwise not routine. |

| Abbreviations: anti-HBc, hepatitis B core antibody; anti-HBs, hepatitis B surface antibody; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G; IgM, immunoglobulin M.

Note:

|

||||

| Table 2: Interpretation of HBV Screening Test Results | ||||

| HBsAg | Anti-HBs | Anti-HBc | Interpretations | |

| IgG | IgM | |||

| Negative | Negative | Negative | Negative | Susceptible to HBV infection |

| Negative | Positive | Negative | Negative | Immune due to HBV vaccination |

| Negative | Positive | Positive | Negative | Immune due to natural HBV infection |

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Positive | Acute HBV infection |

| Positive | Negative | Positive | Negative/Positive | Chronic HBV infection |

| Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative/Positive | Isolated anti-HBc positivity [a]. Possible interpretations:

|

| Abbreviation: HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Note:

|

|||

| Table 3: Interpretation of HCV Test Results [a] | |||

| Anti-HCV | HCV RNA | Interpretations | Response |

| Positive | Detected | Acute or chronic HCV infection | Evaluate for treatment |

| Positive | Not detected |

|

|

| Negative | Detected |

|

|

| Negative | Unknown | Presumed absence of HCV infection if the HCV RNA testing was not performed or the status is unknown | Perform HCV antibody testing based on risk factors |

Routine Screening and Primary Prevention

In patients with HIV, age- and risk-based screening and prevention are cornerstones of adult primary care, and for the most part, the standard recommendations are the same as for adults who do not have HIV. Notable exceptions include anal and cervical dysplasia and other STI screening.

Anatomical inventory: In addition to all elements of a standard patient history and physical examination, an anatomical inventory is necessary to avoid defining primary care needs based on a patient’s gender expression. A matter-of-fact anatomical inventory will identify present and absent organs: penis, testes, prostate, breasts, vagina, cervix, uterus, and ovaries.

| Abbreviations: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BRCA, breast cancer; DHHS, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; MSM, men who have sex with men; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; USPSTF, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. |

| Checklist 3: Recommended Age-, Sex-, and Risk-Based Screening (alphabetical order) |

Abdominal aortic aneurysm: See USPSTF recommendations (2019)

Anal dysplasia and cancer: See NYSDOH AI recommendations (2022)

Bone density/osteoporosis: See USPSTF recommendations (2018)

Breast cancer: See USPSTF recommendations (2024)

Cardiovascular disease: See American College of Cardiology: ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus and American Heart Association: Characteristics, Prevention, and Management of Cardiovascular Disease in People Living With HIV (2019)

Cervical dysplasia and cancer: See NYSDOH AI recommendations (2022)

Colorectal cancer: See USPSTF recommendations (2021)

Depression: See USPSTF recommendations (2023)

Intimate partner violence, elder abuse, and abuse of vulnerable adults: See USPSTF recommendations (2018)

Lung cancer: See USPSTF recommendations (2021)

Prostate cancer: See USPSTF recommendations (2018)

Substance use: See NYSDOH AI recommendations (2024)

|

Download Checklist 3: Recommended Age-, Sex-, and Risk-Based Screening Printable PDF

| Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; DHHS, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; USPSTF, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. |

| Checklist 4: Primary Prevention for Adults With HIV (alphabetical order) |

Breast cancer: See USPSTF recommendations (2019)

Cardiovascular disease: See:

Falls prevention: See USPSTF recommendations (2024)

Neural tube defects: See USPSTF recommendations (2023)

Sexually transmitted infections: Discuss recommended vaccinations. See:

Skin cancer: See USPSTF recommendations (2018)

Smoking: See USPSTF recommendations (2021)

|

Download Checklist 4: Primary Prevention for Adults With HIV Printable PDF

Opportunistic Infection Prevention

The incidence of and mortality related to OIs have decreased since the early days of the HIV epidemic, but OIs remain a concern Masur 2015. Although the median initial CD4 cell count in individuals newly diagnosed with HIV has risen through the years NYSDOH 2019, a significant number of people have low CD4 cell counts at HIV diagnosis and are at risk for OIs Tominski, et al. 2017; Ransome, et al. 2015. Clinicians who care for patients with HIV should be able to identify common OIs and know when to provide and discontinue appropriate prophylaxis (see Table 4, below, and DHHS: Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections in Adults and Adolescents With HIV).

| Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; IgG, immunoglobulin G; MAC, Mycobacterium avium complex; PJP, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia; TE, Toxoplasma gondii encephalitis; TMP/SMX, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Notes:

|

|||

| Table 4: Opportunistic Infection Prophylaxis for Adults With HIV [a] | |||

| Opportunistic Infection | Indications for Initiation and Discontinuation of Primary Prophylaxis | Preferred and Alternative Agent(s) | Indications for Discontinuation of Secondary Prophylaxis |

| Cryptococcosis | Primary prophylaxis is not routinely recommended. | N/A |

|

| Cytomegalovirus | Primary prophylaxis is not routinely recommended. | N/A |

|

| Mycobacterium avium complex | Initiation: Use only if CD4 count is <50/cells mm3 and patient does not initiate ART. Not recommended for individuals who are initiating ART or are taking ART and have an undetectable viral load.

Discontinuation: Taking fully suppressive ART |

Preferred: Azithromycin (weekly) or clarithromycin (twice daily) |

|

| Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (formerly Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia) | Initiation: CD4 count <200 cells/mm3 (or <14%) or history of oropharyngeal candidiasis

Discontinuation: Taking ART and CD4 count ≥200 cells/mm3 for ≥3 months |

Preferred: TMP/SMX single strength once daily

Alternatives:

|

|

| Toxoplasma gondii encephalitis [b,d] | Initiation: CD4 count <100 cells/mm3 and positive serology for Toxoplasma gondii (IgG+)

Discontinuation: Taking ART and CD4 count >200 cells/mm3 for >3 months |

Preferred: TMP/SMX double strength once daily

Alternatives:

|

|

Download Table 4: Opportunistic Infection Prophylaxis for Adults With HIV Printable PDF

Oral Health

Dental Standards of Care Committee, May 2016

Oral health care is a critical component of comprehensive HIV medical management. Development of oral pathology is frequently associated with an underlying progression of HIV disease status. A thorough soft-tissue examination may reveal pathology associated with dysphagia or odynophagia. Dental problems can result in or exacerbate nutritional problems. In addition, psychosocial and quality of life issues frequently are associated with the condition of the oral cavity and the dentition.

Medications and oral health: Many of the medications taken by patients with HIV have adverse effects that may manifest in the oral cavity. Potential adverse effects include the following:

- Candidal growth: Antibiotics may cause or exacerbate

- Xerostomia: Antihistamines, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antihypertensives, and anticholinergic agents

- Increased risk of dental caries: Clotrimazole troches and nystatin suspension pastilles (contain sugar)

- Gingival hyperplasia: Phenytoin

- Oral ulcers: Zalcitabine (DDC)

Selected good practices:

- Dental care referral: Include as part of every primary healthcare initial visit; semiannual oral healthcare visits are essential to dental prophylaxis and other appropriate preventive care. In the later stages of HIV disease, greater numbers of oral lesions and aggressive periodontal breakdown are more likely and may necessitate oral healthcare visits more frequently than twice per year.

- Oral examination: Include a visual examination and palpation of the patient’s lips, labial and buccal mucosa, all surfaces of the tongue and palate, and floor of the mouth in the overall physical examination performed during a primary care visit. The gingiva should be examined for signs of erythema, ulceration, or recession. Refer patients found to have oral mucosal, gingival, or dental lesions to an oral health care provider as soon as possible for appropriate diagnostic evaluation and treatment.

- Oral care education: Include preventive oral health care in primary care patient education to stress the importance of regular dental visits, brushing, flossing, and the use of fluorides and antimicrobial rinses.

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS: PRIMARY CARE FOR ADULTS WITH HIV |

Approach to Care

Opportunistic Infection Prophylaxis

|

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; OI, opportunistic infection. |

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

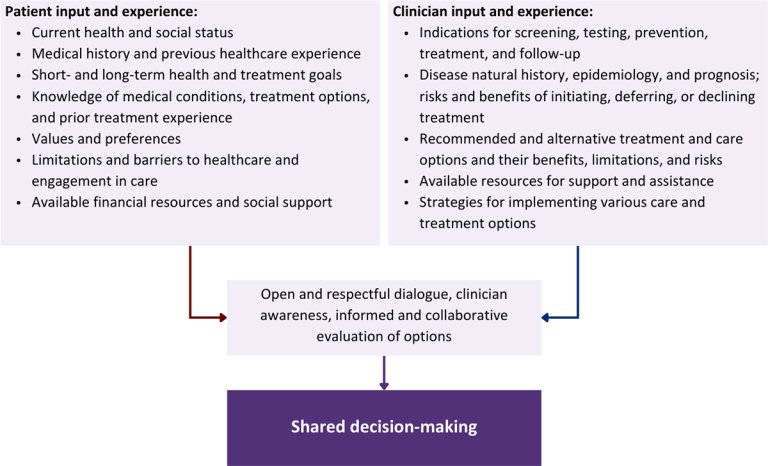

Rationale

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Aberg J. A., Gallant J. E., Ghanem K. G., et al. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with HIV: 2013 update by the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2014;58(1):1-10. [PMID: 24343580]

Alpalhão M., Borges-Costa J., Filipe P. Psoriasis in HIV infection: an update. Int J STD AIDS 2019;30(6):596-604. [PMID: 30813860]

Althoff K. N., Gebo K. A., Moore R. D., et al. Contributions of traditional and HIV-related risk factors on non-AIDS-defining cancer, myocardial infarction, and end-stage liver and renal diseases in adults with HIV in the USA and Canada: a collaboration of cohort studies. Lancet HIV 2019;6(2):e93-104. [PMID: 30683625]

Althoff K. N., McGinnis K. A., Wyatt C. M., et al. Comparison of risk and age at diagnosis of myocardial infarction, end-stage renal disease, and non-AIDS-defining cancer in HIV-infected versus uninfected adults. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60(4):627-38. [PMID: 25362204]

Altice F., Evuarherhe O., Shina S., et al. Adherence to HIV treatment regimens: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Patient Prefer Adherence 2019;13:475-90. [PMID: 31040651]

Avgousti H., Feinstein M. J. Prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease in HIV: practical insights in an evolving field. Top Antivir Med 2023;31(5):559-65. [PMID: 38198667]

Baker J. V., Peng G., Rapkin J., et al. Poor initial CD4+ recovery with antiretroviral therapy prolongs immune depletion and increases risk for AIDS and non-AIDS diseases. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;48(5):541-46. [PMID: 18645520]

Basso M., Andreis S., Scaggiante R., et al. Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and human herpesvirus 8 salivary shedding in HIV positive men who have sex with men with controlled and uncontrolled plasma HIV viremia: a 24-month longitudinal study. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18(1):683. [PMID: 30567494]

Bazzi A. R., Drainoni M. L., Biancarelli D. L., et al. Systematic review of HIV treatment adherence research among people who inject drugs in the United States and Canada: evidence to inform pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) adherence interventions. BMC Public Health 2019;19(1):31. [PMID: 30621657]

Bertz R. J., Persson A., Chung E., et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of atazanavir-containing antiretroviral regimens, with or without ritonavir, in patients who are HIV-positive and treatment-naïve. Pharmacotherapy 2013;33(3):284-94. [PMID: 23456732]

Bigna J. J., Kenne A. M., Asangbeh S. L., et al. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the global population with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2018;6(2):e193-202. [PMID: 29254748]

Bogart L. M., Barreras J. L., Gonzalez A., et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of an intervention to improve coping with intersectional stigma and medication adherence among HIV-positive Latinx sexual minority men. AIDS Behav 2021;25(6):1647-60. [PMID: 33231847]

Bogart L. M., Mutchler M. G., Goggin K., et al. Randomized controlled trial of Rise, a community-based culturally congruent counseling intervention to support antiretroviral therapy adherence among Black/African American adults living with HIV. AIDS Behav 2023;27(5):1573-86. [PMID: 36399252]

Borges A. H., Dubrow R., Silverberg M. J. Factors contributing to risk for cancer among HIV-infected individuals, and evidence that earlier combination antiretroviral therapy will alter this risk. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2014;9(1):34-40. [PMID: 24225382]

Bosh K. A., Coyle J. R., Hansen V., et al. HIV and viral hepatitis coinfection analysis using surveillance data from 15 US states and two cities. Epidemiol Infect 2018;146(7):920-30. [PMID: 29636119]

Bourgi(a) K., Rebeiro P. F., Turner M., et al. Greater weight gain in treatment-naive persons starting dolutegravir-based antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2020;70(7):1267-74. [PMID: 31100116]

Bourgi(b) K., Jenkins C. A., Rebeiro P. F., et al. Weight gain among treatment-naïve persons with HIV starting integrase inhibitors compared to non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors or protease inhibitors in a large observational cohort in the United States and Canada. J Int AIDS Soc 2020;23(4):e25484. [PMID: 32294337]

Bower M., Weir J., Francis N., et al. The effect of HAART in 254 consecutive patients with AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma. AIDS 2009;23(13):1701-6. [PMID: 19550283]

Brennan-Ing M., Seidel L., Rodgers L., et al. The impact of comprehensive case management on HIV client outcomes. PLoS One 2016;11(2):e0148865. [PMID: 26849561]

Brickman C., Palefsky J. M. Human papillomavirus in the HIV-infected host: epidemiology and pathogenesis in the antiretroviral era. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2015;12(1):6-15. [PMID: 25644977]

Brown J., Roy A., Harris R., et al. Respiratory symptoms in people living with HIV and the effect of antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax 2017;72(4):355-66. [PMID: 27965402]

Brown L. L., Perkins J. M., Shepherd B. E., et al. Piloting safety and stabilization: a multi-component trauma intervention to improve HIV viral suppression, retention in care, and post-traumatic stress disorder in a southern United States HIV service organization. AIDS Behav 2024;28(1):174-85. [PMID: 37751108]

Bruchfeld J., Correia-Neves M., Källenius G. Tuberculosis and HIV coinfection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2015;5(7):a017871. [PMID: 25722472]