Clinical Guidelines Program Approach to Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

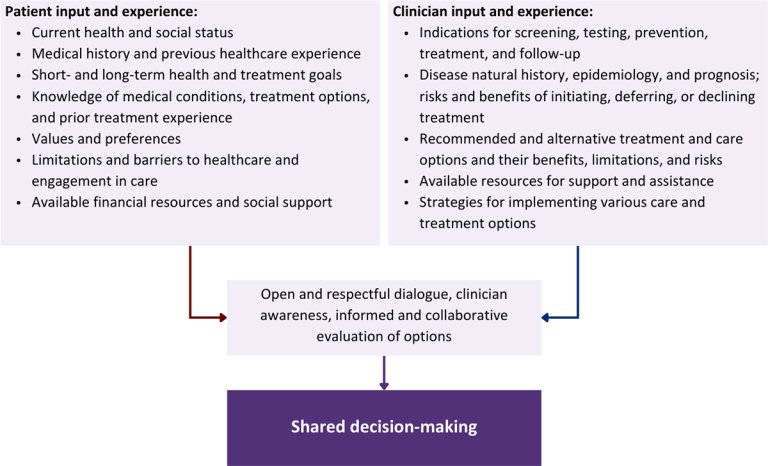

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

NYSDOH HIV Care Provider Definitions

Throughout HIV-related guidelines and other materials, when reference is made to “experienced HIV care provider” or “expert HIV care provider,” those terms are referring to the following 2017 NYSDOH AI definitions:

- Experienced HIV care provider: Practitioners who have been accorded HIV Experienced Provider status by the American Academy of HIV Medicine or have met the HIV Medicine Association’s definition of an experienced provider are eligible for designation as an HIV Experienced Provider in New York State. Nurse practitioners and licensed midwives who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV in collaboration with a physician may be considered HIV Experienced Providers as long as all other practice agreements are met (8 NYCRR 79-5:1; 10 NYCRR 85.36; 8 NYCRR 139-6900). Physician assistants who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV under the supervision of an HIV Specialist physician may also be considered HIV Experienced Providers (10 NYCRR 94.2)

- Expert HIV care provider: A provider with extensive experience in the management of complex patients with HIV.

Q/A: HIV Testing

Download the NYSDOH AI Q/A: HIV Testing Printable PDF

Reviewed and updated: Aisha Khan, DO, and Christine Kerr, MD; March 2019

Who Should be Tested for HIV?

What does the NYSDOH AIDS Institute guideline recommend for HIV screening in the general population?

Healthcare providers should offer HIV testing to all individuals ≥13 years old as part of routine healthcare.

What does New York State public health law require with regard to HIV testing?

New York State public health law requires that all individuals aged ≥13 years old receiving care in a primary care setting, an emergency room, or a hospital be offered an HIV test at least once. The law also mandates that care providers offer an HIV test to any person, regardless of age, if there is evidence of activity that puts an individual at risk of HIV acquisition.

Who should be offered ongoing testing for HIV?

Healthcare providers should offer an HIV test at least annually to all individuals whose behavior increases their risk for exposure to HIV (such behavior includes condomless anal sex, sex with multiple or anonymous partners, needle-sharing, or sex with partners who share needles). Since many people choose not to disclose risk behaviors, care providers should consider adopting a low threshold for recommending HIV testing.

Also, any individual who has been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection (STI) should be offered HIV testing.

How often should HIV screening be performed in individuals who engage in high-risk behavior?

Patients who engage in high-risk behavior should be screened every 3 months. Healthcare providers should provide or refer these individuals for ongoing medical care, risk-reduction counseling and services, and HIV prevention, such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Access to care and prevention are important to maintain the health of individuals at risk and to prevent transmission by those who acquire HIV.

How often should HIV screening be performed in individuals who do not fall into a high-risk behavior category?

According to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in 2 individuals with HIV have had the virus at least 3 years before diagnosis. Many of these individuals did not acknowledge themselves to be at high risk. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force notes that for individuals not engaged in the high-risk behavior outlined above but still at increased risk, a somewhat longer interval (for example, 3 to 5 years) may be adopted. A change in sex partner or marital status merits repeat HIV screening. Routine rescreening may not be necessary for individuals who have not been at increased risk since they were found to be HIV-negative. Women screened during a previous pregnancy should be rescreened in subsequent pregnancies.

Consent

Is written consent required before an HIV test is ordered?

As of May 17, 2017, neither written nor oral consent is needed before ordering an HIV test; however, patients must be informed that an HIV test will be performed, and they may opt-out.

Recommended HIV Test

What is the best test to use for HIV screening?

The optimal test for screening is an HIV antigen/antibody (Ag/Ab) combination immunoassay, which is a laboratory-based test that uses serum or plasma.

Can a rapid point-of-care test be used for HIV screening?

Yes, although it will detect antibodies later in the course of HIV infection and may miss early infection in many cases. There are also newer point-of-care tests that detect antigens and, therefore, earlier infection. It is worth clarifying with your facility which rapid test is used.

Which HIV test should be performed in an individual who has been diagnosed with an STI?

The optimal HIV test is always an HIV Ag/Ab combination immunoassay.

Should an Ag/Ab combination immunoassay be used to screen for HIV in individuals who are taking PrEP?

Yes, that is the optimal test. A rapid point-of-care test can be performed at the same time so patients have an immediate answer, but the rapid test should not replace the Ag/Ab combination immunoassay. If exposure is recent (within the past 10 days) or the patient has signs or symptoms of acute HIV, an HIV RNA test should be ordered.

HIV Testing Follow-Up

What follow-up is recommended if the HIV Ag/Ab combination immunoassay is reactive but the confirmatory HIV-1/HIV-2 Ab differentiation immunoassay is indeterminate or negative?

An HIV-1 viral load test will differentiate acute HIV infection from a false-positive screening result.

What follow-up is recommended if an individual has a reactive point-of-care rapid test (such as OraQuick)?

As follow-up, the healthcare provider should:

- Perform an HIV Ag/Ab combination immunoassay and counsel the patient that the result of the rapid test is preliminary pending the result of the confirmatory HIV test and follow-up Ab differentiation immunoassay.

- Discuss the patient’s option of starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) while awaiting confirmatory test results.

- Screen for suicidality and domestic violence, and make sure the patient is safe.

- Make sure a return appointment is scheduled so test results can be delivered in person.

What follow-up is recommended when a patient’s HIV Ag/Ab combination immunoassay is reactive?

In this scenario, the healthcare provider should:

- Have the patient’s specimens tested for HIV-1 and HIV-2 antibodies using an Ab differentiation immunoassay with reflex. Always include “with reflex” so, if indicated, additional recommended tests are conducted on the same specimen.

- If the results are negative or indeterminate, then perform an HIV-1 RNA test.

- Interpret the final result based on a combination of test results. The NYSDOH Testing Toolkit provides more information about HIV diagnostic tests and the CDC/Association of Public Health Laboratories Laboratory Testing Algorithm in Serum/Plasma. The NYSDOH AI guideline HIV Testing may be consulted as well.

- Discuss ART initiation at the time of a positive result with the first rapid test. Initiation of ART during acute infection may have a number of beneficial clinical outcomes.

- When a diagnosis of acute HIV infection is made, discuss the importance of notifying all recent contacts, and refer patients to partner notification services as mandated by New York State Law. The Department of Health can provide assistance if necessary.

What follow-up is recommended if an individual’s HIV test is negative, but they remain at high risk of acquiring HIV?

In this scenario, the healthcare provider should discuss and/or recommend PrEP and ensure that the patient has access to PrEP services. The healthcare provider should also provide risk-reduction counseling (e.g., safer sex practices, needle exchange, post-exposure prophylaxis [PEP]) and advise retesting for HIV every 3 months for as long as the individual is at risk.

Detection of HIV

How soon after infection can HIV be detected with existing HIV tests?

The length of time depends on which HIV test is used. The “window period” is the time between acquiring HIV infection and the time when a specific diagnostic test can detect HIV. For example, as early as approximately 18 days after infection, an Ag/Ab combination immunoassay may be positive for HIV, reliably up to 45 days (window period for laboratory tests) or 90 days (window period for rapid test) afterward. It takes approximately 10 days after infection for HIV viral load to be detectable on an HIV RNA test.

Can a person who has HIV transmit the virus to another person during the window period?

Yes.

Acute HIV Infection

What is acute HIV infection and when should it be considered?

Acute HIV infection is the very early initial stage of HIV infection when the virus is multiplying rapidly and the body has not yet developed antibodies to fight it. Clinicians should consider acute HIV infection if a patient presents with a clinical syndrome consistent with acute HIV.

What are the symptoms of acute HIV infection?

Symptoms of acute HIV infection are similar to those of influenza and may include fever, fatigue, malaise, joint pains, headache, loss of appetite, rash, night sweats, myalgia, nausea, diarrhea, and pharyngitis.

Which laboratory tests should be ordered for an individual who is suspected of having acute HIV?

The healthcare provider should order an HIV-1 RNA test (viral load) and an HIV Ag/Ab combination immunoassay.

- If HIV RNA is not detected, then no further testing is needed.

- Detection of ≥5,000 copies/mL of HIV RNA indicates a preliminary diagnosis of HIV infection.

- Detection of HIV RNA with <5,000 copies/mL requires repeat HIV RNA testing.

- If a diagnosis of HIV infection is made on the basis of HIV RNA testing alone, then the clinician should collect a new specimen 3 weeks after the first and repeat HIV diagnostic testing.

| KEY POINT |

|

Is a person with acute HIV able to transmit the virus to others?

Yes. A person’s HIV viral load rises quickly during the acute phase, which makes the virus highly transmissible.

When treating a pregnant individual who has acute HIV, should the healthcare provider consult with a specialist?

If acute HIV infection is suspected in a pregnant individual, the care provider should first order HIV RNA testing and an Ag/Ab combination immunoassay (recommended) or Ab differentiation immunoassay (alternative) HIV test. If the HIV RNA test is positive or the HIV test is reactive, then, as soon as possible, the care provider should consult with or refer the patient to a clinician who is experienced in diagnosing and evaluating acute HIV infection.

| KEY POINT |

|

PrEP and PEP

Should all patients who are tested for HIV be offered PrEP?

PrEP should be offered to all individuals whose behavior may expose them to HIV. PrEP should be prescribed as part of a comprehensive prevention strategy that includes risk-reduction counseling about safer sex practices, condom use, and safer injection practices, as well as referral to syringe exchange programs and drug treatment services when appropriate.

| KEY POINT |

|

What is the recommended response to an individual who reports a possible exposure to HIV?

Exposure to HIV is a medical emergency that requires a prompt response.

- A person who reports a potential exposure to HIV should be given a first dose of antiretroviral medications for PEP immediately (ideally within 2 hours of the exposure). The effectiveness of PEP diminishes over time, and PEP is not effective if initiated more than 72 hours after a potential exposure.

- Once the first dose of PEP has been administered, then evaluation of the exposure and recommended testing of the exposed individual and the source (if available) can be performed.

- Refer to the NYSDOH AI guideline PEP to Prevent HIV Infection for more information, including recommendations for PEP regimens and follow-up HIV testing. Guidelines are available for PEP following occupational and non-occupational exposure to HIV and following sexual assault.

Should an individual who has been exposed to HIV be tested more than once?

The NYSDOH AI guideline PEP to Prevent HIV Infection recommends serial HIV testing, with the first test at baseline (at the time the person presents for PEP) and then at 4 and 12 weeks after exposure.

Where can I learn more about PEP (including the antiretroviral medications used for PEP) and PrEP?

See the NYSDOH AI guidelines PEP to Prevent HIV Infection and PrEP to Prevent HIV and Promote Sexual Health.

How to Find an Expert in HIV Care

How do I locate a healthcare provider with experience in treating patients with HIV, for consultation or referral?

The NYSDOH Clinical Education Initiative (CEI) provides access to HIV specialists through their toll-free CEI Line: 1-866-637-2342.

Learn More

Related NYSDOH AI guidelines and resources:

- HIV Testing

- Diagnosis and Management of Acute HIV Infection

- Rapid ART Initiation

- Selecting an Initial ART Regimen

- NYS Good Practices to Prevent Perinatal HIV Transmission

- PEP to Prevent HIV Infection

- PrEP to Prevent HIV and Promote Sexual Health

Other NYSDOH resources:

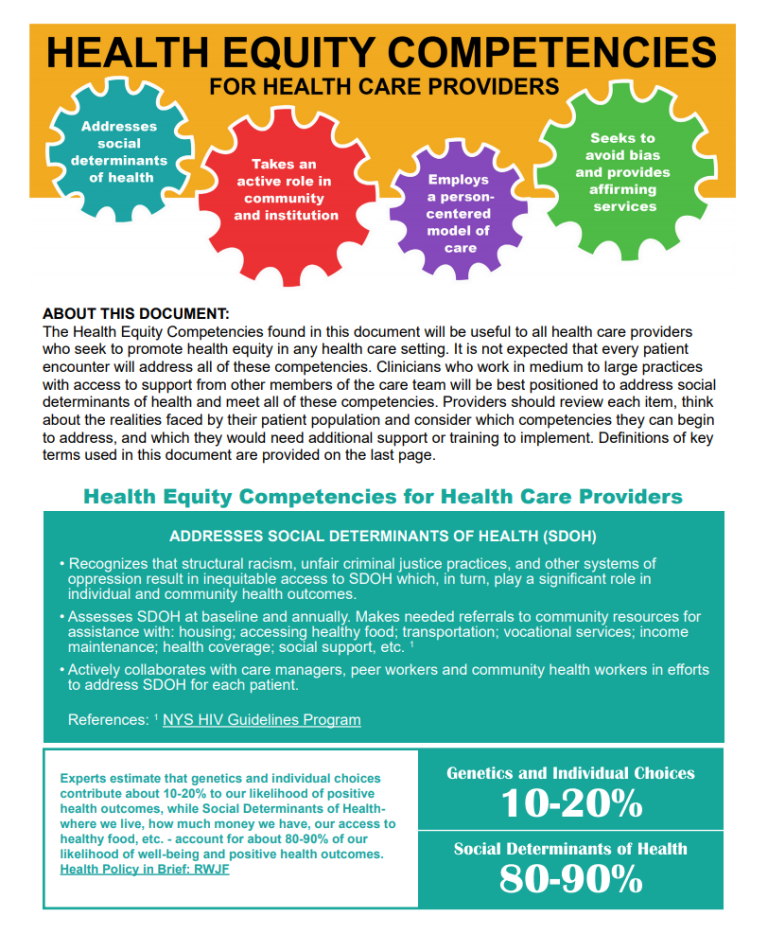

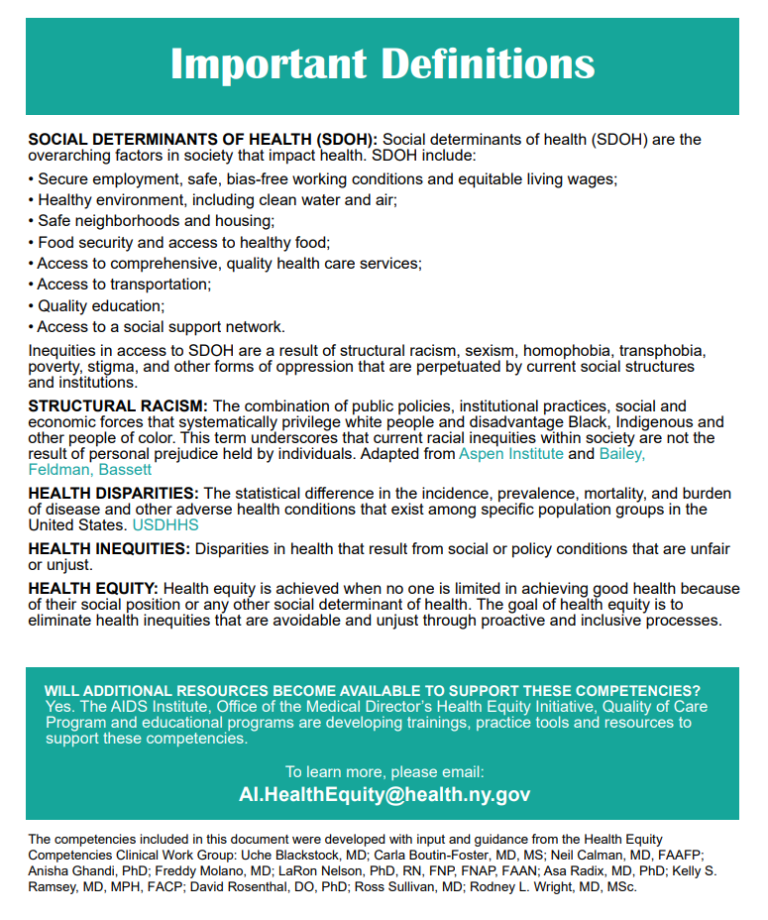

NYSDOH Health Equity Competencies for Health Care Providers

August 2021

Download Printable PDF of Health Equity Competencies

Health Equity Competencies Page 1

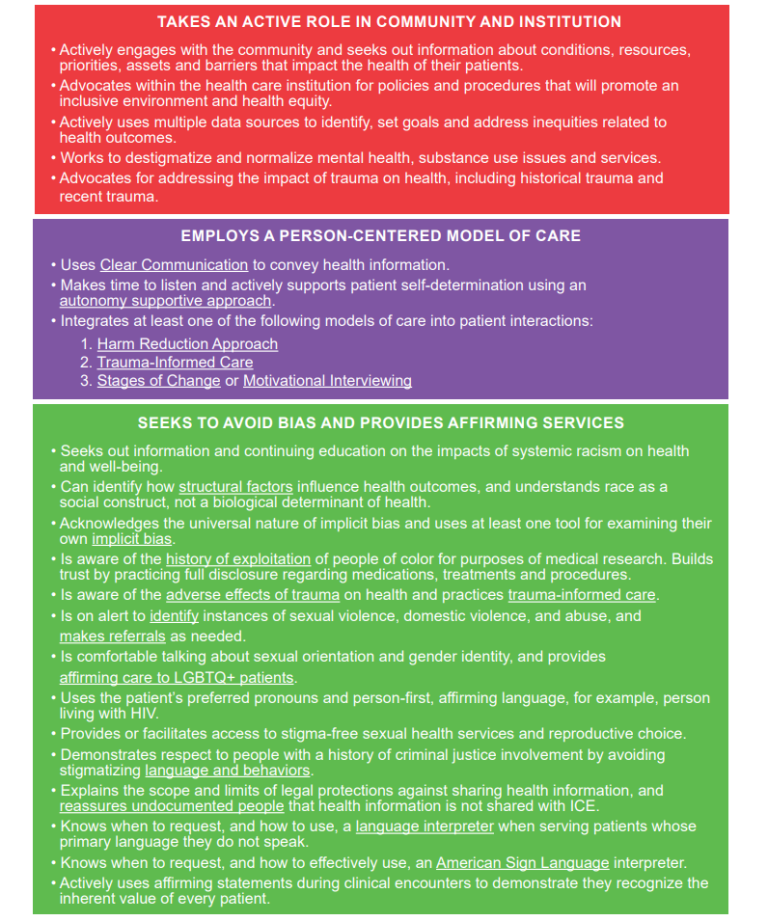

Health Equity Competencies Page 2

Health Equity Competencies Page 3

Selected Links: Resources for Clinicians

June 2022

New York State Department of Health:

- AIDS Institute Training Centers

- Beyond Status

- CEI: HIV Primary Care and Prevention, Sexual Health, HCV Treatment, and Drug User Health

- Communicable Disease Reporting

- Court-Ordered HIV Testing of Defendants

- Ending the AIDS Epidemic in New York State

- Expanded HIV Testing

- HIV/AIDS Laws & Regulations

- HIV/AIDS Testing, Reporting and Confidentiality of HIV-Related Information

- HIV Testing

- HIV Testing, Reporting and Confidentiality in New York State 2017-18 Update: Fact Sheet and Frequently Asked Questions

- Occupational Exposure and HIV Testing FAQ

- Partner Services: What Health Care Providers Need to Know

- Provider Reporting & Partner Services

- Rapid Testing for HIV

- Rules, Regulations & Laws

- Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Wadsworth Center (HIV-1/2 adult and pediatric testing)

New York City Health:

- Contact Notification Assistance Program (CNAP)

- Reporting Diseases and Conditions

- Sexual Health Clinics

AIDS Education & Training Center: National HIV Curriculum

American Academy of HIV Medicine: HIV Testing

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:

- 2018 Quick reference guide: Recommended laboratory HIV testing algorithm for serum or plasma specimens

- Advantages and Disadvantages of FDA-Approved HIV Assays Used for Screening

- False-Positive HIV Test Results

- HIV Testing

- STI Treatment Guidelines

Gay & Lesbian Medical Association: Guidelines for Care of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Patients

Infectious Diseases Society of America: Diagnosis of Infectious Diseases

National Coalition for Sexual Health:

- A New Approach to Sexual History Taking: Talking About Pleasure, Problems, and Pride During a Sexual History (videos)

- Sexual Health and Your Patients: A Provider’s Guide

Scientific American: Life Cycle of HIV Animation (2018)

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: HIV Testing

Selected Links: Resources for Consumers

June 2022

New York State Department of Health:

American Academy of HIV Medicine: Patient Assistance Resources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: HIV Testing Basics

Migrant Clinicians Network: Sexual Assault

NAM Aidsmap: Testing and Health Monitoring

The Body: HIV Testing: What You Need to Know

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Getting Tested

All FDA-Approved HIV Medications, With Brand Names and Abbreviations

Reviewed April 2024

Listed below are all FDA-approved HIV medications as of March 23, 2023, per HIVinfo.NIH.gov, with links to the Clinical Info HIV.gov drug database. The list is organized by drug class, with individual drugs listed in alphabetical order. Combination drugs are also listed in alphabetical order.

Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs): characteristics

- Abacavir (ABC; Ziagen): FDA label | Patient info

- Emtricitabine (FTC; Emtriva): FDA label | Patient info

- Lamivudine (3TC; Epivir): FDA label | Patient info

- Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF; Viread): FDA label | Patient info

- Zidovudine (AZT, ZDV; Retrovir): FDA label | Patient info

Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs): characteristics

- Doravirine (DOR; Pifeltro): FDA label | Patient info

- Efavirenz (EFV; Sustiva): FDA label | Patient info

- Etravirine (ETR; Intelence): FDA label | Patient info

- Nevirapine (NVP; Viramune, Viramune XR [extended release]): FDA label | Patient info

- Rilpivirine (RPV; Edurant): FDA label | Patient info

Protease Inhibitors (PIs): characteristics

- Atazanavir (ATV; Reyataz): FDA label | Patient info

- Darunavir (DRV; Prezista): FDA label | Patient info

- Fosamprenavir (FPV; Lexiva): FDA label | Patient info

- Ritonavir (RTV; Norvir): FDA label | Patient info

- Tipranavir (TPV; Aptivus): FDA label | Patient info

Fusion Inhibitor: characteristics

- Enfuvirtide (T-20; Fuzeon): FDA label | Patient info

CCR5 Antagonist: characteristics

- Maraviroc (MVC; Selzentry): FDA label | Patient info

Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTIs): characteristics

- Cabotegravir (CAB; Vocabria): FDA label | Patient info

- Dolutegravir (DTG; Tivicay): FDA label | Patient info

- Raltegravir (RAL; Isentress, Isentress HD): FDA label | Patient info

Attachment Inhibitor: characteristics

- Fostemsavir (FTR; Rukobia): FDA label | Patient info

Post-Attachment Inhibitor: characteristics

- Ibalizumab-uiyk (IBA; Trogarzo): FDA label | Patient info

Capsid Inhibitor: characteristics

- Lenacapavir (LEN; Sunlenca): FDA label | Patient info

Pharmacokinetic Enhancer: characteristics

- Cobicistat (COBI; Tybost): FDA label | Patient info

Combination HIV Medications:

- Abacavir/Lamivudine (ABC/3TC; Epzicom): FDA label | Patient info

- Abacavir/Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (ABC/DTG/3TC; Triumeq, Triumeq PD): FDA label | Patient info

- Abacavir/Lamivudine/Zidovudine (ABC/3TC/ZDV; Trizivir): FDA label | Patient info

- Atazanavir/Cobicistat (ATV/COBI; Evotaz): FDA label | Patient info

- Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide Fumarate (BIC/FTC/TAF; Biktarvy): FDA label | Patient info

- Cabotegravir/Rilpivirine (CAB/RPV; Cabenuva): FDA label | Patient info

- Darunavir/Cobicistat (DRV/COBI; Prezcobix): FDA label | Patient info

- Darunavir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alefenamide (DRV/COBI/FTC/TAF; Symtuza): FDA label | Patient info

- Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (DTG/3TC; Dovato): FDA label | Patient info

- Dolutegravir/Rilpivirine (DTG/RPV; Juluca): FDA label | Patient info

- Doravirine/Lamivudine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (DOR/3TC/TDF; Delstrigo): FDA label | Patient info

- Efavirenz/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (EFV/FTC/TDF; Atripla): FDA label | Patient info

- Efavirenz/Lamivudine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (EFV/3TC/TDF; Symfi, Symfi Lo): FDA label | Patient info

- Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide Fumarate (EVG/COBI/FTC/TAF; Genvoya): FDA label | Patient info

- Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF; Stribild): FDA label | Patient info

- Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/Tenofovir Alafenamide Fumarate (FTC/RPV/TAF; Odefsy): FDA label | Patient info

- Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (FTC/RPV/TDF; Complera): FDA label | Patient info

- Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Alafenamide Fumarate (FTC/TAF; Descovy): FDA label | Patient info

- Emtricitabine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (FTC/TDF; Truvada): FDA label | Patient info

- Lamivudine/Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (3TC/TDF; Cimduo): FDA label | Patient info

- Lamivudine/Zidovudine (3TC/ZDV; Combivir): FDA label | Patient info

- Lopinavir/Ritonavir (LPV/r; Kaletra): FDA label | Patient info

Last updated on November 29, 2023