Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: October 21, 2020

Lead authors: Jennifer McNeely, MD, MS, NYU Grossman School of Medicine; Angeline Adam, MD, New York City Health + Hospitals/Kings County; Susan D. Whitley, MD; Alan Rodriguez Penney, MD, SUNY Downstate Medical Center

Writing group: Timothy J. Wiegand, MD, FACMT, FAACT, DFASAM; Sharon L. Stancliff, MD; Narelle Ellendon, RN; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Substance Use Guidelines Committee

Date of original publication: October 21, 2020

This guideline on screening and risk assessment for substance use in adults (≥18 years old) was developed by the New York State (NYS) Department of Health (DOH) AIDS Institute (AI) for use by primary care providers and in other adult outpatient care settings in NYS to achieve the following goals:

- Increase the identification of unhealthy substance use among NYS residents and increase access to evidence-based interventions for appropriate patients. “Unhealthy substance use” refers to a spectrum of use that increases the risk of health consequences and ranges from hazardous or risky patterns of use to severe substance use disorder (SUD).

- Increase the number of clinicians in NYS who perform substance use screening and risk assessment as an integral part of primary care.

- Provide clinicians with guidance on selecting validated substance use screening and risk assessment tools and on providing or referring for evidence-based interventions.

- Promote a harm reduction approach to the identification and treatment of substance use and SUDs, which involves practical strategies and ideas aimed at reducing the negative consequences associated with substance use.

Role of primary care providers in New York State: Primary care providers in NYS play an essential role in identifying and addressing unhealthy substance use in their patients. In light of the potential consequences of alcohol and drug use for individuals, communities, and healthcare systems, this committee recommends that all primary care providers in NYS be prepared to perform or provide substance use screening, assessment of risk level, and brief interventions as appropriate.

Definition of Terms

Screening

Screening entails asking patients brief questions about substance use and should be routinely performed by care providers for all patients seen in medical settings. This guideline recommends substance use screening for all adults seen by primary care providers. Screening can quickly identify patients with potentially unhealthy substance use (see Box 1, below), many of whom will not have substance use–related clinical signs or symptoms Saitz(b), et al. 2014; Gordon, et al. 2013. Most screening instruments are brief and may be as short as a single question; therefore, they do not collect detailed information on the risk level, duration, or specific pattern of substance use.

| Box 1: Unhealthy Substance Use |

|

Risk Assessment

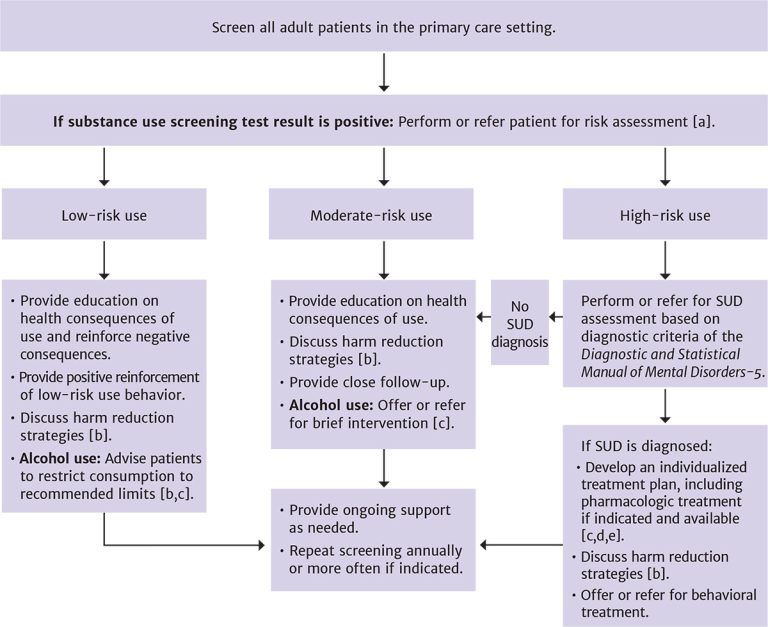

Risk assessment is performed using brief assessment tools to collect information on the extent, duration, and pattern of an individual patient’s substance use. Assessment tools determine the level of risk (i.e., low, moderate, or high) and thus the potential for negative consequences (see Box 2, below). This guideline recommends that clinicians use only validated questionnaires for risk assessment in patients who have a positive screening result or a history of SUD or overdose. As shown in Figure 1, below, risk level and other individual patient factors guide clinicians in recommending appropriate interventions and informing patients about the potential consequences of their substance use McNeely(a), et al. 2016; Saitz 2005.

| Box 2: Substance Use Levels of Risk [a] |

|

|

Note:

|

Figure 1: Substance Use Identification and Risk Assessment in Primary Care

Notes:

- For patients with a known history of SUD or overdose, screening may not be required but assessment is recommended.

- See NYSDOH AI guideline Substance Use Harm Reduction in Medical Care.

- See NYSDOH AI guideline Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism: Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide.

- See NYSDOH AI guideline Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder.

- See U.S. Public Health Service: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence.

Download figure: Substance Use Identification and Risk Assessment in Primary Care

Goals of Screening and Risk Assessment

In the United States, tobacco, alcohol, and other (e.g., illicit, nonmedical prescription) drug use are among the top 10 leading causes of preventable death, accounting for more than 500,000 deaths per year White, et al. 2020; GBD 2018. Alcohol-related deaths have doubled in the past 2 decades; in 2017, there were more than 72,500 alcohol-related deaths in the United States White, et al. 2020. Increases in opioid use disorder and skyrocketing rates of drug overdose deaths (often opioid-related) are a public health crisis across the country Wilson, et al. 2020; Dowell, et al. 2017; Rudd, et al. 2016; SAMHSA 2016.

Patient visits to healthcare settings are an opportunity for clinicians to identify substance use and related problems, offer timely interventions, and provide or link patients to treatment when indicated. Screening and treatment for tobacco use have been widely adopted as core clinical quality measures for primary care CMS 2013, but alcohol and drug use screening is not as widely performed, and use is substantially under-recognized WHO 2016; Venkatesh and Davis 2000. Although screening for alcohol use has been a recommended practice in adult primary care since 1996 Curry, et al. 2018, only 1 in 6 adults in the United States report ever discussing alcohol use with a healthcare professional McKnight-Eily, et al. 2014.

Screening for substance use in primary care is generally well accepted by patients as a marker of quality care Simonetti, et al. 2015; Miller, et al. 2006. However, for patients and care providers to be comfortable, thoughtful implementation, with sensitivity to stigma and privacy concerns, is essential Bradley, et al. 2020; McNeely, et al. 2018 (see the NYSDOH AI guideline Substance Use Harm Reduction in Medical Care > Avoiding Substance Use-Associated Discrimination).

The goals of screening for and assessing substance use in primary care vary by practice setting and resources and may include:

- Informing medical care: One goal is to inform a patient’s medical care. Substance use is an important aspect of medical history because it can significantly affect disease processes, response to treatment, and exposure to health risks. Knowledge of a patient’s substance use informs a care provider’s diagnosis of other medical and psychiatric conditions and alerts them to associated health risks (e.g., overdose, liver disease) and common comorbid conditions (e.g., depression). Similar to knowing about a patient’s past medical history, family history, or social determinants of health, knowing about a patient’s substance use helps care providers formulate effective patient-centered treatment plans.

- Identifying the need for intervention: A second goal is to identify patients who would benefit from interventions to reduce their consumption (see guideline section Management of Low-, Moderate-, and High-Risk Substance Use) or patients who are candidates for substance use disorder treatment (see Figure 1: Substance Use Identification and Risk Assessment in Primary Care). Evidence-based interventions are available, including brief interventions for moderate-risk alcohol use, pharmacotherapy for opioid and alcohol use disorders, and treatment for smoking cessation Patnode, et al. 2020; Curry, et al. 2018; Jonas, et al. 2014; Mattick, et al. 2014; USPHS 2008. Such treatments can be delivered effectively in a primary care setting, but they remain underused.

- Engaging patients: Another goal is opening the conversation and engaging patients in discussion about substance use; if done with knowledge and sensitivity, this may reduce stigma, improve the patient–care provider relationship, and lead to behavior change. Initiating a discussion about substance use communicates to patients that it is a health issue, not a moral failing, and that their care provider is concerned enough about substance use to address it and offer help.

| KEY POINT |

|

Substance Use Screening for All Adult Patients in the Primary Care Setting

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Primary Care Screening for Adults

|

| KEY POINTS |

|

Alcohol

In primary care settings, clinicians should screen all adult patients ≥18 years old for alcohol use. A large body of evidence indicates that screening tools can accurately identify unhealthy alcohol use (see Table 1: Recommended Validated Tools for Use in Medical Settings to Screen for Alcohol and Drug Use in Adults) and that brief counseling interventions can reduce alcohol use, improve health, and be cost-effective Patnode, et al. 2020; O'Connor, et al. 2018; O'Donnell, et al. 2014; Kaner, et al. 2009; McNeely, et al. 2008; Solberg, et al. 2008; Maciosek, et al. 2006. The National Committee on Quality Assurance adopted alcohol screening and brief intervention as a quality indicator in 2018 and incorporated it into the widely used Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) performance measures.

In the absence of systematic screening, unhealthy alcohol use typically goes unidentified McKnight-Eily, et al. 2017 or is identified by healthcare providers only when an individual has developed a severe alcohol use disorder or alcohol-related health problems, such as alcohol-related cirrhosis or pancreatitis. In a study among individuals reporting current alcohol use, only 17.4% reported ever discussing their use with a health professional, and the rate was only modestly higher (25.4%) for those who reported binge drinking McKnight-Eily, et al. 2017.

Tobacco

Clinicians should screen all patients for all types of tobacco use, and when it is identified, provide counseling, assessment, and treatment USPHS 2008. Every visit with a healthcare provider affords the opportunity to identify a patient’s tobacco use and offer effective cessation interventions. Screening for tobacco use is often accomplished with 1 question: “Have you ever smoked cigarettes or used any other kind of tobacco?” Patients who answer “yes” should be asked about frequency and level of use in the past 30 days (e.g., number of cigarettes smoked per day) AHRQ 2008. Despite concern about increasing rates of e-cigarette use, screening for electronic nicotine delivery systems is not currently a recommended practice Krist, et al. 2021.

Drugs

Based on clinical experience and expertise, this committee recommends that clinicians screen for drug use in adult patients ≥18 years old who present for primary care. The decision to screen should consider the rationale and specific circumstances discussed below and should only be performed for the purpose of informing clinical care. Screening should identify a patient’s use of illicit drugs and nonmedical use of prescription drugs that can be misused (e.g., opioids, benzodiazepines, and stimulants).

Evidence supports the accuracy of validated screening questionnaires in adults Patnode, et al. 2020; however, data on the effectiveness of drug screening plus brief intervention to reduce drug use and associated health consequences are currently limited, and this is an area of active research. Randomized controlled clinical trials have generated mixed results regarding the efficacy of brief interventions in reducing drug use Patnode, et al. 2020; Gelberg, et al. 2015; Roy-Byrne, et al. 2014; Saitz(a), et al. 2014; Humeniuk, et al. 2012.

Evidence supports the benefits of pharmacologic treatment for opioid use disorder, which can be delivered effectively in primary care settings. However, no pharmacotherapy is currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for other types of drug use disorders. Some patients with unhealthy use of drugs other than opioids will benefit from referral to addiction treatment or from psychosocial interventions integrated into primary care, but data on long-term outcomes of interventions in primary care settings are scarce, and many patients may not have access to evidence-based services USPSTF 2020.

No currently published studies demonstrate harms associated with screening adult primary care patients for drug use, although the potential for harm does exist Saitz 2020. For some patients, especially those who are pregnant or planning to conceive, positive results from a drug screening test could pose social or legal consequences, such as required reporting and the potential for involvement of child protective services (see discussion below). It is essential that care providers respect the sensitivity of any substance use information documented in patients’ health records and ensure that patients understand privacy protections for their health information.

Rationale for screening: This committee’s rationale for recommending drug use screening in adult patients, even with the potential for harm in some specific circumstances, is based on the following:

- Stigma is a significant barrier to identifying and treating unhealthy drug use or substance use disorders (SUDs). The exclusion of routine screening for drug use may perpetuate the perception that discussion of drug use with healthcare providers is taboo. This is especially the case if alcohol and tobacco use are discussed openly but drug use is not mentioned. Routine, matter-of-fact, nonjudgmental screening for drug use may help reduce stigma by normalizing this discussion.

- The social history that clinicians currently perform typically includes questions about alcohol, tobacco, and drug use but may not collect this information in a systematic and clinically useful manner. It is important that clinicians screen for drug use consistently, in a nonbiased manner, and use standardized, evidence-based screening tools.

- Opioid overdose deaths can be reduced through increased identification of unhealthy opioid use and, when indicated, effective treatment with medications for opioid use disorder SAMHSA 2019; Sordo, et al. 2017; Cousins, et al. 2016.

- Identifying and addressing unhealthy drug use, including drug use disorders, may positively affect other patient outcomes. For instance, identification of nonmedical benzodiazepine use in a patient receiving opioids for chronic pain could inform overdose prevention counseling, opioid prescribing, and provision of naloxone to reduce the patient’s overdose risk.

- Knowledge of a patient’s drug use is essential for accurate diagnosis and treatment. For example, in a patient who uses cocaine, chest pain could be the result of drug use rather than a blocked coronary artery, but without knowledge of the drug use, the healthcare provider will not have the information necessary to perform the appropriate diagnostic work-up. In addition, knowledge of drug use may be essential for an accurate diagnosis of psychiatric disorders, and knowledge of injection drug use can help guide screening for infections.

| KEY POINT |

|

Screening in individuals who are pregnant or planning to conceive: Because there are potential legal and social consequences of a positive drug use screening result in individuals who are pregnant or planning to conceive, this committee urges caution when performing drug use screening. It is essential to engage patients in shared and informed decision-making before screening is performed. Fully informed consent includes clear discussion and confirmed patient understanding of the potential harms, consequences, and benefits of screening. For patients who are pregnant or planning to conceive, the informed consent discussion should include:

- Description of drug screening processes and procedures.

- Potential benefits of drug screening for the patient.

- Discussion of how results are interpreted and likely next steps if the screening result is positive.

- Confirmation of confidentiality of the patient’s medical information.

- Description of the CAPTA law and legal requirements for healthcare providers when screening results are positive.

- Discussion of the patient’s ability to refuse drug screening without repercussions, except in cases in which screening is mandated by an employer or by the court.

- Psychosocial support and counseling about potential harms of drugs and treatment options for SUD, if patients decline to be screened for other drugs.

Repeat screening to inform clinical care in individual patient circumstances: Iatrogenic harm is possible if a patient’s drug use is not identified, including adverse effects resulting from drug-medication interactions, overdose from combining prescribed medications with illicit drugs, and withdrawal syndromes when a patient’s drug use is undisclosed and they are unable to use, such as during hospitalization Lindsey, et al. 2012; CDC 2007; Antoniou and Tseng 2002.

Clinicians should repeat substance use screening in patients who have symptoms or other medical conditions that could be caused or exacerbated by substance use, such as chest pain, liver disease, or mood disorders Kim, et al. 2017; Edelman and Fiellin 2016; NIAAA 2016; Ries, et al. 2014; Mertens, et al. 2005; Lock and Kaner 2004.

Screening is also recommended for patients who use medications that have adverse interactions with alcohol or drugs and for patients who engage in known risk behaviors, such as unprotected sex, that may co-occur with substance use Maxwell, et al. 2019; McKetin, et al. 2018; Scott-Sheldon, et al. 2016; Rehm, et al. 2012. Patients taking prescription opioids or benzodiazepines should be screened for use of alcohol and for illicit or nonmedical use of other sedating drugs (including other opioids or benzodiazepines) that can increase the risk of overdose. Patients taking any controlled substances should be assessed for co-occurring substance use that may increase the probability of engaging in risky use of prescribed medications or of having or developing an SUD. Specific assessment tools (e.g., Opioid Risk Tool, Current Opioid Misuse Measure) have been developed to predict and evaluate prescription opioid misuse among patients receiving chronic opioid therapy, but discussion of these tools is beyond the scope of this guideline. Care providers should be aware of potential interactions between alcohol or drugs and medications, such as antiretroviral, pain management, or neurologic medications (e.g., gabapentin and pregabalin) Gomes, et al. 2017; Lyndon, et al. 2017; Lindsey, et al. 2012; Bruce, et al. 2008; Saitz 2005; Antoniou and Tseng 2002. When counseling patients who use substances about drug-medication interactions, care providers should be clear about the safety of their prescribed medications and be certain to encourage adherence to all critical medications, such as antiretroviral treatment Kalichman, et al. 2015.

See the following resources for checking drug interactions:

- Drugs.com > Drug Interactions Checker

- University of Liverpool HEP Drug Interactions Checker

- University of Liverpool HIV Drug Interactions Checker

- Consensus validation of the POSAMINO (POtentially Serious Alcohol–Medication INteractions in Older adults) criteria Holton, et al. 2017

- NYSDOH AI Resource: ART Drug-Drug Interactions

- For patients: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism > Harmful Interactions: Mixing Alcohol With Medicines

| Implementing Substance Use Screening in Primary Care Settings |

|

Screening Tools

| RECOMMENDATION |

Screening Tools

|

Successful substance use screening relies on accurate patient self-report. Although urine toxicology, measures of blood alcohol level, or other laboratory testing may detect the presence of substances used very recently, (typically hours or ≤4 days after the last use), these tests are not appropriate for identifying unhealthy use, which may be intermittent and occur over time Bosker and Huestis 2009; Cone and Huestis 2007; Verstraete 2004. Laboratory screening tests for alcohol and drugs do not provide information about the severity or consequences of use, and thus provide less information than questionnaires.

There is no reliable biomarker with sufficient sensitivity and specificity to identify the range of drinking behaviors that constitute unhealthy alcohol use Afshar, et al. 2017; Jarvis, et al. 2017; Jatlow, et al. 2014; Stewart, et al. 2014; Verstraete 2004; Neumann and Spies 2003. For drug use, urine, saliva, and blood testing are not recommended as replacements for questionnaire-based screening because laboratory tests have a brief window of detection (typically 1 to 4 days) Bosker and Huestis 2009; Cone and Huestis 2007; Verstraete 2004. Although hair testing has a more extended detection period, the cost and lack of reliability for detecting occasional drug use decrease its utility in primary care Verstraete 2004.

Note:

|

||

| Table 1: Recommended Validated Tools for Use in Medical Settings to Screen for Alcohol and Drug Use in Adults | ||

| Tool [a] | Substance(s) Included | No. of Items, Approximate Time Required to Complete, and Format |

| AUDIT-C (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Concise) Bradley, et al. 2007; Bush, et al. 1998

|

|

|

| SISQ-Alc (Single-Item Screening Questions for Alcohol) McNeely(b), et al. 2015; Smith, et al. 2009 |

|

|

| SISQ-Drug (Single-Item Screening Questions for Drug Use) McNeely(b), et al. 2015; Smith, et al. 2010 |

|

|

| SoDU (Screen of Drug Use) Tiet, et al. 2015 |

|

|

| SUBS (Substance Use Brief Screen) McNeely and Saitz 2015 |

|

|

| TAPS-1 (Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance Use) Gryczynski, et al. 2017 |

|

|

| KEY POINT |

|

An optimal screening instrument will quickly and accurately identify individuals with the full spectrum of unhealthy use, fit into the existing clinical workflow, and have flexible administration options (i.e., self- or interviewer-administered). To facilitate patient report of substance use, the language used in any screening tool should be clear and nonjudgmental. Drug screening should capture nonmedical prescription drug use and illicit drug use. Table 1, above, lists recommended substance use screening tools.

The briefest approach to screening may be to use the Single-Item Screening Questions (SISQ) for alcohol or drug use (SISQ-Alc and -Drug). SISQ tools are validated for interviewer administration or self-administration and have good sensitivity and specificity. A positive response on SISQ tools identifies unhealthy use in the past year but does not indicate the level of risk. Both the Substance Use Brief Screen (SUBS) and the first section of the Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance Use (TAPS-1) tool elicit information about use of tobacco, alcohol, illicit drugs, and nonmedical prescription drugs through a single 4-item instrument. Like the SISQ-Alc and -Drug, the SUBS and TAPS-1 tools screen for any use in the past year, and a positive response indicates unhealthy use but does not identify level of risk.

In some circumstances, the purpose of screening may be to diagnose substance use disorder rather than identify unhealthy drug use. For example, if the clinical setting cannot offer early intervention or preventive care, screening may be used to identify individuals in need of referral to addiction treatment. In such cases, the Screen of Drug Use (SoDU) tool, which specifically identifies drug use disorders, may be used. The SoDU was validated using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–IV (DSM-IV) criteria, and a positive screen corresponds to a DSM-IV diagnosis of “drug abuse or dependence.”

Alcohol: The briefest alcohol screening questionnaires (SISQ-Alc, TAPS-1, SUBS) use a single question about binge drinking in the past year to identify unhealthy alcohol use. Although it is possible for patients to use more alcohol than the recommended limits in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Agriculture Dietary Guidelines (14 drinks/week for men ≤65 years old, 7 drinks/week for women and men ≥65 years old), even in the absence of binge drinking, validation studies have demonstrated good sensitivity NIAAA 2016; DHHS 2015. The 3-item Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test–Concise (AUDIT-C) is a widely used and recommended brief screening tool for alcohol use in medical settings Moyer 2013; Frank, et al. 2008; Bradley, et al. 2007; Reinert and Allen 2007; Bradley, et al. 2003; Bush, et al. 1998. Unlike the other brief screening tools, the AUDIT-C identifies the level of risk to patients with problem use and high-risk use. The AUDIT-C does not screen for tobacco or drugs.

Tobacco: Tobacco use is incorporated into some of the brief screening instruments (SUBS, TAPS-1) included in Table 1, above. The accuracy of SUBS and TAPS-1 tools for identifying tobacco use is high, with a sensitivity of 98% and a specificity ranging from 80% to 96% Gryczynski, et al. 2017; McNeely(a), et al. 2015. Use of a single instrument that concurrently screens for tobacco and alcohol use will streamline the screening process.

Drugs: Screening for drug use can be performed with the SISQ-Drug, SUBS, or TAPS-1 tools, all of which perform well in validation studies of adults in primary care settings Gryczynski, et al. 2017; McNeely(a), et al. 2016; McNeely(a), et al. 2015; McNeely(b), et al. 2015. With changes in the legal status of cannabis and shifting attitudes toward cannabis use, clinics should provide patients and staff with clear instructions about reporting cannabis use on questionnaires that categorize cannabis as an illicit drug Lapham, et al. 2017. In states where cannabis is legal, it may be best to ask about its use separately from illicit drugs Sayre, et al. 2020.

Risk Assessment

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Risk Assessment

|

Candidates for Risk Assessment

Clinicians should use validated tools to perform substance use assessment in individual patients who have any of the characteristics discussed below. The purpose of assessment is to identify the level of risk (low, moderate, or high) posed by a patient’s substance use to guide clinical decisions about intervention, treatment, and follow-up (see Figure 1: Substance Use Identification and Risk Assessment in Primary Care).

Positive substance use screening test: Given current levels of substance use in the general population and the negative effects of unhealthy substance use, any positive screening test result should prompt an efficient and accurate risk assessment McNeely(a), et al. 2015; McNeely(b), et al. 2015.

Known history of SUD or overdose: Polysubstance use is common in people with SUD Callaghan, et al. 2018; Falk, et al. 2006; McLellan, et al. 2000; Earleywine and Newcomb 1997. For patients with a history of SUD, identification of all substances used, including tobacco, and assessment of the associated levels of risk are indicated for early intervention and clinical decision-making. SUDs are chronic conditions, and even patients with long periods of abstinence remain vulnerable to resuming previous patterns of use McLellan, et al. 2000. Patients with a history of SUD may reduce or stop use of one substance but develop unhealthy use of a different substance (e.g., alcohol) Lin, et al. 2021; Callaghan, et al. 2018; Wang, et al. 2017; Falk, et al. 2006; Earleywine and Newcomb 1997. Furthermore, overdose is frequently the result of polysubstance use, often involving use of opioids in combination with alcohol and other drugs Tori, et al. 2020. In patients with a history of nonfatal overdose, it is critically important to conduct an assessment and identify all of the substances being used; the results will guide education and treatment to reduce the risk of another overdose.

The level of risk of associated with substance use in individuals who are planning to become pregnant should inform counseling, particularly in light of the risk of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder that occurs early in pregnancy May, et al. 2018; Moyer 2013; Stade, et al. 2009; Floyd, et al. 2008; Floyd, et al. 2006; DHHS 2005; CDC 2003. In addition, it is reasonable to perform a substance use assessment in patients with chronic diseases who have poor adherence to treatment recommendations or are not responding as expected to treatment of their medical condition Garin, et al. 2017; Daskalopoulou, et al. 2014.

Risk Assessment Tools

Substance use assessment tools are designed to collect information on the quantity, frequency, and duration of substance use and to indicate a risk level (see Table 2, below).

Note:

|

||

| Table 2: Brief, Validated Risk Assessment Tools for Use in Medical Settings With Adults ≥18 Years Old [a] | ||

| Tool [a] | Substance(s) Included | No. of Items, Approximate Time Required to Complete, and Format |

| ASSIST (Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test) Humeniuk, et al. 2008

|

Tobacco, alcohol, prescription drugs, other drugs; identifies specific drug classes |

|

| ACASI-ASSIST (Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview–ASSIST) Kumar, et al. 2016; McNeely(b), et al. 2016 |

Tobacco, alcohol, prescription drugs, other drugs; identifies specific drug classes |

|

| AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) Reinert and Allen 2007

|

Alcohol |

|

| DUDIT (Drug Disorders Identification Test) Hildebrand 2015; DUDIT 2003

|

All drugs; does not identify drug classes |

|

| DAST-10 (Drug Abuse Screening Test) Yudko, et al. 2007; Skinner 1982

|

All drugs; does not identify drug classes |

|

| TAPS (Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance Use) Adam, et al. 2019; McNeely(a), et al. 2016 |

Tobacco, alcohol, prescription drugs, other drugs; identifies specific drug classes |

|

Alcohol use: To assess level of risk in patients who use alcohol, clinicians can use the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) or the AUDIT-Concise (AUDIT-C) tool, both of which have been widely adopted in medical settings NIAAA 2016; Bradley, et al. 2007; Reinert and Allen 2007; Bradley, et al. 2003. The AUDIT is a 10-item questionnaire developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) for alcohol use screening in medical settings. The AUDIT-C consists of the first 3 items of the AUDIT, which asks only about alcohol consumption. Although the full AUDIT is still widely used, the 3-item AUDIT-C performs as well as the full 10-item AUDIT instrument for identifying risky use and problem use in studies conducted among primary care patients in the United States Bradley, et al. 2007. However, use of the full AUDIT provides expanded information about problems related to alcohol use that may be helpful for care providers offering brief interventions or other alcohol counseling.

Tobacco use: For patients who use tobacco, assessment of health risks is typically accomplished by asking about the number of cigarettes smoked per day. The 2-item Heaviness of Smoking Index, which asks about total cigarettes per day and the timing of the first cigarette, can determine the level of dependence for daily smokers.

Drug use: For assessment of drug use, which can involve multiple substance classes with varying levels of risk, the instruments are by necessity more complex. The WHO Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) was one of the first screening tools designed for use in healthcare settings to provide substance-specific risk stratification for drugs. Its length and complexity have hindered its implementation in primary care settings Ali, et al. 2013; Babor, et al. 2007, but a self-administered electronic version may be more feasible McNeely(b), et al. 2016.

The more recently developed Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance Use (TAPS) tool streamlines the ASSIST to perform this assessment relatively quickly and still supply substance-specific information about the level of risk. Scores range from 0 to 4, with higher scores indicating greater severity. The TAPS tool was specifically developed for adult primary care and is recommended for use in general medical settings to screen for opioid and other substance use SAMHSA 2018. It is validated in an electronic, patient self-administered format (myTAPS) Adam, et al. 2019 and a more traditional interviewer-administered questionnaire. An online version of the TAPS tool with clinical guidance on interpreting the scores and resources for intervention is available on the National Institute on Drug Abuse TAPS website.

Management of Low-, Moderate-, and High-Risk Substance Use

Assessment with validated tools can characterize the level of risk as low, moderate, or high (see Figure 1: Substance Use Identification and Risk Assessment in Primary Care and Table 2: Brief, Validated Risk Assessment Tools for Use in Medical Settings With Adults ≥18 Years Old). Intervention options for substance use are determined by the level of risk identified in the assessment process, an individual’s perception of the problem, and time restrictions, among other factors. Individuals with unhealthy substance use regularly interact with the healthcare system, and primary care settings are optimally positioned to offer prevention and treatment interventions. All clinicians can develop the skills to offer treatment or refer patients for appropriate interventions McLellan 2017; Edelman and Fiellin 2016.

Harm reduction strategies should be discussed with individuals who engage in substance use at all risk levels.

Clinical resources for addressing tobacco use include the NYSDOH Information about Tobacco Use, Smoking and Secondhand Smoke, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene publication Treating Tobacco Addiction, and the American Academy of Family Physicians table of FDA-Approved Medications for Smoking Cessation. For patients who use any type of tobacco, the U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline for Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update recommends the “5 As” approach as an intervention:

- Ask patients about tobacco use.

- Advise tobacco users to quit.

- Assess willingness to quit.

- Assist in a quit attempt.

- Arrange for follow-up.

For individuals with low-risk use of any substance, clinicians can offer positive reinforcement and reminders of the negative consequences of use. For individuals who use alcohol, clinicians can provide information on the recommended limits of use; see the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Department of Agriculture Dietary Guidelines. Robust evidence supports the efficacy of screening and brief interventions in the primary care setting for reducing alcohol use among individuals with unhealthy use who do not meet criteria for alcohol use disorder Curry, et al. 2018; Jonas, et al. 2012. Studies on the efficacy of brief interventions in reducing drug use have found mixed results Gelberg, et al. 2015; Roy-Byrne, et al. 2014; Saitz(a), et al. 2014; Humeniuk, et al. 2012; however, brief interventions are recommended by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and have been implemented in many healthcare settings with no evidence of harm SAMHSA 2018. If an individual has high-risk substance use, it is essential to perform or refer for a full diagnostic substance use disorder assessment using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–5 criteria (see guideline section Diagnosis of Substance Use Disorder).

Brief interventions: Brief interventions range from 5 to 20 minutes in duration, vary in frequency, and include a variety of components based on different psychological and motivational approaches. Common elements of a brief intervention include discussion of the risks and benefits of substance use as perceived by the patient, individualized feedback regarding level of risk, advice on reducing use to within recommended safe limits, discussion of any related health effects, and motivational support (see Figure 2, below). A commonly used acronym is FRAMES: Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu Options, Empathy, and Self-Efficacy. The time available for an intervention and the individual’s level of engagement and motivation for change often determine the duration, type, and frequency of brief interventions.

For further information and resources, see the NYSDOH AI guideline Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder > Behavioral Treatment.

Figure 2: Brief Intervention: “Can We Spend a Few Minutes Talking About Your Substance Use?”

Adapted from Project ASSERT 2019.

Download figure: Brief Intervention: “Can We Spend a Few Minutes Talking About Your Substance Use?”

Diagnosis of Substance Use Disorder

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Diagnosis of Substance Use Disorder

|

Healthcare providers should perform or refer patients for a full assessment based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria to accurately diagnose an SUD (see Table 3, below) APA 2013. The DSM-5 criteria can accurately diagnose the SUD and its severity—mild, moderate, or severe—and the assessment can be performed by the clinician or experienced staff. If expertise or resources are limited, then clinicians may refer the patient to a care provider who can perform the full assessment. Clinicians experienced in assessing and treating SUD may elect to use the DSM-5 criteria as the initial assessment tool.

To enhance patient engagement and increase the possibility that a patient will follow through with the care plan, interventions must be tailored to match an individual’s perception of the problem and their readiness to change NIAAA 2016; VA/DoD 2015; SAMHSA 1997. Based on clinical experience, the diagnostic process is an opportunity to build rapport; explore a patient’s attitudes toward substance use and treatment; dispel any misconceptions about treatment, particularly pharmacologic treatment; and engage patients in care.

Patients often present with concurrent substance use and mental health disorders, and symptoms of one can mimic the other, which can complicate diagnosis and make it more challenging SAMHSA 2019. Clinicians should consider a diagnosis of SUD before establishing a primary psychiatric diagnosis (e.g., consider alcohol-induced depressive disorder before diagnosing a major depressive disorder). Symptoms of intoxication, such as depressed or elevated mood or perceptual disturbances, and symptoms of withdrawal, such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia, can also mimic psychiatric symptoms and should be carefully assessed.

| Abbreviations: DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–5; PCP, phencyclidine; SUD, substance use disorder.

Notes: |

|

| Table 3: DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Diagnosing and Classifying Substance Use Disorders [a,b,c] | |

| Criteria Type | Descriptions |

| Impaired control over substance use

(DSM-5 criteria 1 to 4) |

|

| Social impairment

(DSM-5 criteria 5 to 7) |

|

| Risky use

(DSM-5 criteria 8 and 9) |

|

| Pharmacologic

(DSM-5 criteria 10 and 11) |

|

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS: SUBSTANCE USE SCREENING AND RISK ASSESSMENT IN ADULTS |

Primary Care Screening for Adults

Screening Tools

Risk Assessment

Diagnosis of Substance Use Disorder

|

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

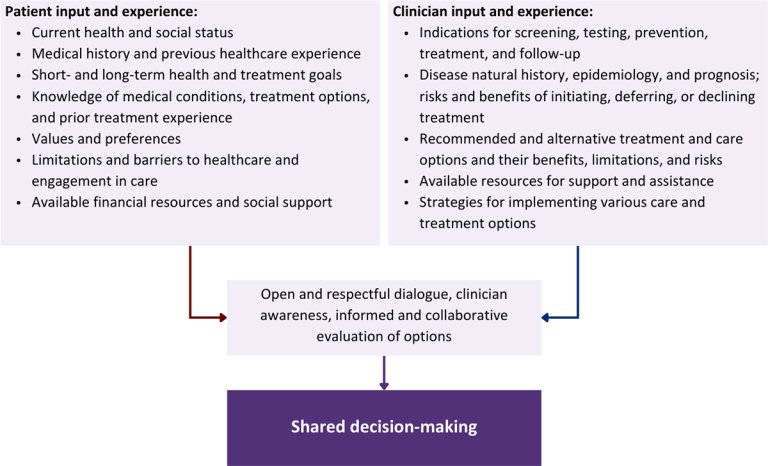

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Adam A., Schwartz R. P., Wu L. T., et al. Electronic self-administered screening for substance use in adult primary care patients: feasibility and acceptability of the tobacco, alcohol, prescription medication, and other substance use (myTAPS) screening tool. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2019;14(1):39. [PMID: 31615549]

Afshar M., Burnham E. L., Joyce C., et al. Cut-point levels of phosphatidylethanol to identify alcohol misuse in a mixed cohort including critically ill patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2017;41(10):1745-53. [PMID: 28792620]

AHRQ. Helping smokers quit: a guide for clinicians. 2008 May. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians/references/clinhlpsmkqt/clinhlpsmksqt.pdf [accessed 2020 Mar 31]

Ali R., Meena S., Eastwood B., et al. Ultra-rapid screening for substance-use disorders: the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST-Lite). Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;132(1-2):352-61. [PMID: 23561823]

Antoniou T., Tseng A. L. Interactions between recreational drugs and antiretroviral agents. Ann Pharmacother 2002;36(10):1598-1613. [PMID: 12243611]

APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed: substance-related and addictive disorders; 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

Babor T. F., McRee B. G., Kassebaum P. A., et al. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT): toward a public health approach to the management of substance abuse. Subst Abus 2007;28(3):7-30. [PMID: 18077300]

Bosker W. M., Huestis M. A. Oral fluid testing for drugs of abuse. Clin Chem 2009;55(11):1910-31. [PMID: 19745062]

Bradley K. A., Bush K. R., Epler A. J., et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med 2003;163(7):821-29. [PMID: 12695273]

Bradley K. A., DeBenedetti A. F., Volk R. J., et al. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007;31(7):1208-17. [PMID: 17451397]

Bradley K. A., Lapham G. T., Hawkins E. J., et al. Quality concerns with routine alcohol screening in VA clinical settings. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26(3):299-306. [PMID: 20859699]

Bradley K. A., Lapham G. T., Lee A. K. Screening for drug use in primary care: practical implications of the new USPSTF recommendation. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180(8):1050-51. [PMID: 32515790]

Bruce R. D., Altice F. L., Friedland G. H. Pharmacokinetic drug interactions between drugs of abuse and antiretroviral medications: implications and management for clinical practice. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 2008;1(1):115-27. [PMID: 24410515]

Bush K., Kivlahan D. R., McDonell M. B., et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med 1998;158(16):1789-95. [PMID: 9738608]

Callaghan R. C., Gatley J. M., Sykes J., et al. The prominence of smoking-related mortality among individuals with alcohol- or drug-use disorders. Drug Alcohol Rev 2018;37(1):97-105. [PMID: 28009934]

CDC. Motivational intervention to reduce alcohol-exposed pregnancies--Florida, Texas, and Virginia, 1997-2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52(19):441-44. [PMID: 12807086]

CDC. Unintentional poisoning deaths--United States, 1999-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56(5):93-96. [PMID: 17287712]

CMS. 2014 Clinical Quality Measures (CQMs): adult recommended core measures. 2013 Jan. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/Downloads/2014_CQM_AdultRecommend_CoreSetTable.pdf [accessed 2020 Mar 31]

Cone E. J., Huestis M. A. Interpretation of oral fluid tests for drugs of abuse. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007;1098:51-103. [PMID: 17332074]

Cousins G., Boland F., Courtney B., et al. Risk of mortality on and off methadone substitution treatment in primary care: a national cohort study. Addiction 2016;111(1):73-82. [PMID: 26234389]

Curry S. J., Krist A. H., Owens D. K., et al. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2018;320(18):1899-1909. [PMID: 30422199]

Daskalopoulou M., Rodger A., Phillips A. N., et al. Recreational drug use, polydrug use, and sexual behaviour in HIV-diagnosed men who have sex with men in the UK: results from the cross-sectional ASTRA study. Lancet HIV 2014;1(1):e22-31. [PMID: 26423813]

DHHS. U.S. Surgeon General releases advisory on alcohol use in pregnancy. 2005 Feb 21. http://come-over.to/FAS/SurGenAdvisory.htm [accessed 2020 Mar 31]

DHHS. Dietary guidelines 2015-2020. Appendix 9. Alcohol. 2015 Dec. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/2015-2020_Dietary_Guidelines.pdf [accessed 2020 Jun 30]

Dowell D., Arias E., Kochanek K., et al. Contribution of opioid-involved poisoning to the change in life expectancy in the United States, 2000-2015. JAMA 2017;318(11):1065-67. [PMID: 28975295]

DUDIT. The Drug Use Disorders Identification Test: DUDIT manual. 2003 Mar. https://paihdelinkki.fi/sites/default/files/duditmanual.pdf [accessed 2020 Oct 14]

Earleywine M., Newcomb M. D. Concurrent versus simultaneous polydrug use: prevalence, correlates, discriminant validity, and prospective effects on health outcomes. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 1997;5(4):353-64. [PMID: 9386962]

Edelman E. J., Fiellin D. A. In the clinic. Alcohol use. Ann Intern Med 2016;164(1):Itc1-16. [PMID: 26747315]

Falk D. E., Yi H. Y., Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. An epidemiologic analysis of co-occurring alcohol and tobacco use and disorders: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Alcohol Res Health 2006;29(3):162-71. [PMID: 17373404]

Floyd R. L., Jack B. W., Cefalo R., et al. The clinical content of preconception care: alcohol, tobacco, and illicit drug exposures. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199(6 Suppl 2):s333-39. [PMID: 19081427]

Floyd R. L., O'Connor M. J., Bertrand J., et al. Reducing adverse outcomes from prenatal alcohol exposure: a clinical plan of action. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2006;30(8):1271-75. [PMID: 16899029]

Frank D., DeBenedetti A. F., Volk R. J., et al. Effectiveness of the AUDIT-C as a screening test for alcohol misuse in three race/ethnic groups. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23(6):781-87. [PMID: 18421511]

Garin N., Zurita B., Velasco C., et al. Prevalence and clinical impact of recreational drug consumption in people living with HIV on treatment: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2017;7(1):e014105. [PMID: 28100565]

GBD. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry 2018;5(12):987-1012. [PMID: 30392731]

Gelberg L., Andersen R. M., Afifi A. A., et al. Project QUIT (Quit Using Drugs Intervention Trial): a randomized controlled trial of a primary care-based multi-component brief intervention to reduce risky drug use. Addiction 2015;110(11):1777-90. [PMID: 26471159]

Gomes T., Juurlink D. N., Antoniou T., et al. Gabapentin, opioids, and the risk of opioid-related death: a population-based nested case-control study. PLoS Med 2017;14(10):e1002396. [PMID: 28972983]

Gordon A. J., Bertholet N., McNeely J., et al. 2013 update in addiction medicine for the generalist. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2013;8(1):18. [PMID: 24499640]

Gryczynski J., McNeely J., Wu L. T., et al. Validation of the TAPS-1: a four-item screening tool to identify unhealthy substance use in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2017;32(9):990-96. [PMID: 28550609]

Hildebrand M. The psychometric properties of the Drug Use Disorders Identification Test (DUDIT): a review of recent research. J Subst Abuse Treat 2015;53:52-59. [PMID: 25682718]

Holton A. E., Gallagher P. J., Ryan C., et al. Consensus validation of the POSAMINO (POtentially Serious Alcohol-Medication INteractions in Older adults) criteria. BMJ Open 2017;7(11):e017453. [PMID: 29122794]

Humeniuk R., Ali R., Babor T., et al. A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for illicit drugs linked to the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in clients recruited from primary health-care settings in four countries. Addiction 2012;107(5):957-66. [PMID: 22126102]

Humeniuk R., Ali R., Babor T. F., et al. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking And Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Addiction 2008;103(6):1039-47. [PMID: 18373724]

Jarvis M., Williams J., Hurford M., et al. Appropriate use of drug testing in clinical addiction medicine. J Addict Med 2017;11(3):163-73. [PMID: 28557958]

Jatlow P. I., Agro A., Wu R., et al. Ethyl glucuronide and ethyl sulfate assays in clinical trials, interpretation, and limitations: results of a dose ranging alcohol challenge study and 2 clinical trials. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014;38(7):2056-65. [PMID: 24773137]

Jonas D. E., Amick H. R., Feltner C., et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2014;311(18):1889-1900. [PMID: 24825644]

Jonas D. E., Garbutt J. C., Amick H. R., et al. Behavioral counseling after screening for alcohol misuse in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2012;157(9):645-54. [PMID: 23007881]

Kalichman S. C., Kalichman M. O., Cherry C., et al. Intentional medication nonadherence because of interactive toxicity beliefs among HIV-positive active drug users. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;70(5):503-9. [PMID: 26226250]

Kaner E. F., Dickinson H. O., Beyer F., et al. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions in primary care settings: a systematic review. Drug Alcohol Rev 2009;28(3):301-23. [PMID: 19489992]

Kim T. W., Bernstein J., Cheng D. M., et al. Receipt of addiction treatment as a consequence of a brief intervention for drug use in primary care: a randomized trial. Addiction 2017;112(5):818-27. [PMID: 27886657]

Krist A. H., Davidson K. W., Mangione C. M., et al. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2021;325(3):265-79. [PMID: 33464343]

Kumar P. C., Cleland C. M., Gourevitch M. N., et al. Accuracy of the Audio Computer Assisted Self Interview version of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ACASI ASSIST) for identifying unhealthy substance use and substance use disorders in primary care patients. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;165:38-44. [PMID: 27344194]

Lapham G. T., Lee A. K., Caldeiro R. M., et al. Frequency of cannabis use among primary care patients in Washington State. J Am Board Fam Med 2017;30(6):795-805. [PMID: 29180554]

Lin L. A., Bohnert A. S., Blow F. C., et al. Polysubstance use and association with opioid use disorder treatment in the US Veterans Health Administration. Addiction 2021;116(1):96-104. [PMID: 32428386]

Lindsey W. T., Stewart D., Childress D. Drug interactions between common illicit drugs and prescription therapies. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 2012;38(4):334-43. [PMID: 22221229]

Lock C. A., Kaner E. F. Implementation of brief alcohol interventions by nurses in primary care: do non-clinical factors influence practice?. Fam Pract 2004;21(3):270-75. [PMID: 15128688]

Lyndon A., Audrey S., Wells C., et al. Risk to heroin users of polydrug use of pregabalin or gabapentin. Addiction 2017;112(9):1580-89. [PMID: 28493329]

Maciosek M. V., Coffield A. B., Edwards N. M., et al. Priorities among effective clinical preventive services: results of a systematic review and analysis. Am J Prev Med 2006;31(1):52-61. [PMID: 16777543]

Mattick R. P., Breen C., Kimber J., et al. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;(2):CD002207. [PMID: 24500948]

Maxwell S., Shahmanesh M., Gafos M. Chemsex behaviours among men who have sex with men: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Drug Policy 2019;63:74-89. [PMID: 30513473]

May P. A., Chambers C. D., Kalberg W. O., et al. Prevalence of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in 4 US communities. JAMA 2018;319(5):474-82. [PMID: 29411031]

McKetin R., Lubman D. I., Baker A., et al. The relationship between methamphetamine use and heterosexual behaviour: evidence from a prospective longitudinal study. Addiction 2018;113(7):1276-85. [PMID: 29397001]

McKnight-Eily L. R., Liu Y., Brewer R. D., et al. Vital signs: communication between health professionals and their patients about alcohol use--44 states and the District of Columbia, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2014;63(1):16-22. [PMID: 24402468]

McKnight-Eily L. R., Okoro C. A., Mejia R., et al. Screening for excessive alcohol use and brief counseling of adults - 17 states and the District of Columbia, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(12):313-19. [PMID: 28358798]

McLellan A. T. Substance misuse and substance use disorders: why do they matter in healthcare?. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc 2017;128:112-30. [PMID: 28790493]

McLellan A. T., Lewis D. C., O'Brien C. P., et al. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA 2000;284(13):1689-95. [PMID: 11015800]

McNeely J., Kumar P. C., Rieckmann T., et al. Barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation of substance use screening in primary care clinics: a qualitative study of patients, providers, and staff. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2018;13(1):8. [PMID: 29628018]

McNeely J., Saitz R. Appropriate screening for substance use vs disorder. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(12):1997-98. [PMID: 26641355]

McNeely J., Windham B. G., Anderson D. E. Dietary sodium effects on heart rate variability in salt sensitivity of blood pressure. Psychophysiology 2008;45(3):405-11. [PMID: 18047481]

McNeely(a) J., Strauss S. M., Saitz R., et al. A brief patient self-administered substance use screening tool for primary care: two-site validation study of the Substance Use Brief Screen (SUBS). Am J Med 2015;128(7):784.e9-19. [PMID: 25770031]

McNeely(a) J., Wu L. T., Subramaniam G., et al. Performance of the Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription medication, and other Substance use (TAPS) tool for substance use screening in primary care patients. Ann Intern Med 2016;165(10):690-99. [PMID: 27595276]

McNeely(b) J., Cleland C. M., Strauss S. M., et al. Validation of Self-Administered Single-Item Screening Questions (SISQs) for unhealthy alcohol and drug use in primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30(12):1757-64. [PMID: 25986138]

McNeely(b) J., Strauss S. M., Rotrosen J., et al. Validation of an Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) version of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in primary care patients. Addiction 2016;111(2):233-44. [PMID: 26360315]

Mertens J. R., Weisner C., Ray G. T., et al. Hazardous drinkers and drug users in HMO primary care: prevalence, medical conditions, and costs. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005;29(6):989-98. [PMID: 15976525]

Miller P. M., Thomas S. E., Mallin R. Patient attitudes towards self-report and biomarker alcohol screening by primary care physicians. Alcohol Alcohol 2006;41(3):306-10. [PMID: 16574672]

Moyer V. A. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2013;159(3):210-18. [PMID: 23698791]

Neumann T., Spies C. Use of biomarkers for alcohol use disorders in clinical practice. Addiction 2003;98 Suppl 2:81-91. [PMID: 14984245]

NIAAA. Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician’s guide. 2016 Jul. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/practitioner/cliniciansguide2005/guide.pdf [accessed 2020 May 6]

NIDA. Screening for drug use in general medical settings – resource guide. 2012 Apr. https://nida.nih.gov/sites/default/files/resource_guide.pdf [accessed 2020 Mar 31]

O'Connor E. A., Perdue L. A., Senger C. A., et al. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions to reduce unhealthy alcohol use in adolescents and adults: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2018;320(18):1910-28. [PMID: 30422198]

O'Donnell A., Anderson P., Newbury-Birch D., et al. The impact of brief alcohol interventions in primary healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. Alcohol Alcohol 2014;49(1):66-78. [PMID: 24232177]

Patnode C. D., Perdue L. A., Rushkin M., et al. Screening for unhealthy drug use: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2020;323(22):2310-28. [PMID: 32515820]

Project ASSERT. SBIRT: Screening Brief Intervention & Referral to Treatment. 2019 Oct 4. https://medicine.yale.edu/sbirt/ [accessed 2020 Mar 31]

Rehm J., Shield K. D., Joharchi N., et al. Alcohol consumption and the intention to engage in unprotected sex: systematic review and meta-analysis of experimental studies. Addiction 2012;107(1):51-59. [PMID: 22151318]

Reinert D. F., Allen J. P. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: an update of research findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007;31(2):185-99. [PMID: 17250609]

Ries R. K., Fiellin D. A., Miller S. C., et al. The ASAM principles of addiction medicine; 2014. https://shop.lww.com/The-ASAM-Principles-of-Addiction-Medicine/p/9781496371010

Roy-Byrne P., Bumgardner K., Krupski A., et al. Brief intervention for problem drug use in safety-net primary care settings: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312(5):492-501. [PMID: 25096689]

Rudd R. A., Seth P., David F., et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(50-51):1445-52. [PMID: 28033313]

Saitz R. Clinical practice. Unhealthy alcohol use. N Engl J Med 2005;352(6):596-607. [PMID: 15703424]

Saitz R. Screening for unhealthy drug use: neither an unreasonable idea nor an evidence-based practice. JAMA 2020;323(22):2263-65. [PMID: 32515804]

Saitz(a) R., Palfai T. P., Cheng D. M., et al. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: the ASPIRE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014;312(5):502-13. [PMID: 25096690]

Saitz(b) R., Cheng D. M., Allensworth-Davies D., et al. The ability of single screening questions for unhealthy alcohol and other drug use to identify substance dependence in primary care. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2014;75(1):153-57. [PMID: 24411807]

SAMHSA. A guide to substance abuse services for primary care clinicians. 1997. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK64827/ [accessed 2020 Mar 31]

SAMHSA. Facing addiction in America: the Surgeon General's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. 2016 Nov. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ [accessed 2020 Mar 31]

SAMHSA. Implementing care for alcohol & other drug use in medical settings: an extension of SBIRT. SBIRT change guide 1.0. 2018 Feb. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Implementing_Care_for_Alcohol_and_Other_Drug_Use_In_Medical_Settings_-_An_Extension_of_SBIRT.pdf [accessed 2020 Mar 31]

SAMHSA. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. 2019 Aug. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/cbhsq-reports/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018/NSDUHNationalFindingsReport2018.pdf [accessed 2020 Jan 6]

Sayre M., Lapham G. T., Lee A. K., et al. Routine assessment of symptoms of substance use disorders in primary care: prevalence and severity of reported symptoms. J Gen Intern Med 2020;35(4):1111-19. [PMID: 31974903]

Schulden J. D., Thomas Y. F., Compton W. M. Substance abuse in the United States: findings from recent epidemiologic studies. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2009;11(5):353-59. [PMID: 19785975]

Scott-Sheldon L. A., Carey K. B., Cunningham K., et al. Alcohol use predicts sexual decision-making: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the experimental literature. AIDS Behav 2016;20 Suppl 1(0 1):s19-39. [PMID: 26080689]

Simonetti J. A., Lapham G. T., Williams E. C. Association between receipt of brief alcohol intervention and quality of care among veteran outpatients with unhealthy alcohol use. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30(8):1097-1104. [PMID: 25691238]

Skinner H. A. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav 1982;7(4):363-71. [PMID: 7183189]

Smith P. C., Schmidt S. M., Allensworth-Davies D., et al. Primary care validation of a single-question alcohol screening test. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24(7):783-88. [PMID: 19247718]

Smith P. C., Schmidt S. M., Allensworth-Davies D., et al. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med 2010;170(13):1155-60. [PMID: 20625025]

Solberg L. I., Maciosek M. V., Edwards N. M. Primary care intervention to reduce alcohol misuse ranking its health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med 2008;34(2):143-52. [PMID: 18201645]

Sordo L., Barrio G., Bravo M. J., et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2017;357:j1550. [PMID: 28446428]

Spear S. E., Shedlin M., Gilberti B., et al. Feasibility and acceptability of an audio computer-assisted self-interview version of the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in primary care patients. Subst Abus 2016;37(2):299-305. [PMID: 26158798]

Stade B. C., Bailey C., Dzendoletas D., et al. Psychological and/or educational interventions for reducing alcohol consumption in pregnant women and women planning pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;(2):CD004228. [PMID: 19370597]

Stewart S. H., Koch D. G., Willner I. R., et al. Validation of blood phosphatidylethanol as an alcohol consumption biomarker in patients with chronic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014;38(6):1706-11. [PMID: 24848614]

Tiet Q. Q., Leyva Y. E., Moos R. H., et al. Screen of drug use: diagnostic accuracy of a new brief tool for primary care. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(8):1371-77. [PMID: 26075352]

Tori M. E., Larochelle M. R., Naimi T. S. Alcohol or benzodiazepine co-involvement with opioid overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2017. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(4):e202361. [PMID: 32271389]

Tourangeau R., Smith T. W. Asking sensitive questions: the impact of data collection mode, question format, and question context. Publ Opin Q 1996;60(2):275-304. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2749691

USPHS. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med 2008;35(2):158-76. [PMID: 18617085]

USPSTF. Interventions for unhealthy drug use—supplemental report: a systematic review. 2020 Jun. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558205/ [accessed 2020 Jan 7]

VA/DoD. Clinical practice guideline for the management of substance use disorders. 2015 Dec. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/sud/VADODSUDCPGRevised22216.pdf [accessed 2020 Mar 31]

Venkatesh V., Davis F. D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies. Management Science 2000;46(2):186-204. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2634758

Verstraete A. G. Detection times of drugs of abuse in blood, urine, and oral fluid. Ther Drug Monit 2004;26(2):200-205. [PMID: 15228165]

Wang L., Min J. E., Krebs E., et al. Polydrug use and its association with drug treatment outcomes among primary heroin, methamphetamine, and cocaine users. Int J Drug Policy 2017;49:32-40. [PMID: 28888099]

White A. M., Castle I. P., Hingson R. W., et al. Using death certificates to explore changes in alcohol-related mortality in the United States, 1999 to 2017. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2020;44(1):178-87. [PMID: 31912524]

WHO. The health and social effects of nonmedical cannabis use. 2016 Nov 11. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241510240 [accessed 2020 Mar 31]

Wight R. G., Rotheram-Borus M. J., Klosinski L., et al. Screening for transmission behaviors among HIV-infected adults. AIDS Educ Prev 2000;12(5):431-41. [PMID: 11063062]

Williams E. C., Achtmeyer C. E., Thomas R. M., et al. Factors underlying quality problems with alcohol screening prompted by a clinical reminder in primary care: a multi-site qualitative study. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30(8):1125-32. [PMID: 25731916]

Wilson N., Kariisa M., Seth P., et al. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69(11):290-97. [PMID: 32191688]

Yudko E., Lozhkina O., Fouts A. A comprehensive review of the psychometric properties of the Drug Abuse Screening Test. J Subst Abuse Treat 2007;32(2):189-98. [PMID: 17306727]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines | |

| Date of original publication | October 21, 2020 |

| Intended users | Primary care clinicians and care providers in other adult outpatient care settings in New York State |