Introduction

Date of current publication: April 12, 2023

Lead author: Abhiram Maddi, PhD, MS, DDS

Contributor: Stephen N. Abel, DDS, MSD

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona Vail, MD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Dental Standards of Care Committee

Date of original publication: March 8, 2017

In some patients with HIV, immunosuppression may allow the development of oral and periodontal lesions Polvora, et al. 2018; Baccaglini, et al. 2007. Chronic periodontitis can influence systemic inflammation favoring viral replication, and periodontal pockets may serve as reservoirs for the virus Polvora, et al. 2018. Periodontal lesions associated with HIV include linear gingival erythema (LGE) and necrotizing periodontal diseases, which are subclassified as necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG), necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP), and necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis (NUS/NS). NUP and NUS/NS may represent different stages of the same pathologic process, with NUP being a more advanced stage of NUG Ryder, et al. 2012; Kaplan, et al. 2009. As the population with HIV ages, patients may develop chronic conditions that can contribute to an exacerbated or enhanced progression of chronic adult periodontitis Stabholz, et al. 2010. There is also a concern about oral hygiene care and the incidence of periodontal disease in youth with perinatally acquired HIV, who may be at higher risk for developing significant periodontal disease associated with tooth loss and HIV progression. Frequent dental care is needed to prevent potential periodontal progression in this population Ryder, et al. 2020; Moscicki, et al. 2019. Stricter periodontal recall and oral hygiene care within older/aging and perinatally infected youth are critical.

The identification of periodontal diseases may be critical even in patients receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART). While the introduction of highly active ART has significantly reduced this incidence Ntolou, et al. 2023; Mataftsi, et al. 2011, the occurrence of oral and periodontal infections despite ART may indicate the failure of ART or the development of viral resistance Mataftsi, et al. 2011. It has also been suggested that the oral microbiome of patients on ART may affect systemic and periodontal inflammation. A shift in the microbiome is most likely due to a complex relationship between HIV, ART, and aging Griffen, et al. 2019; Toljic, et al. 2018; Noguera-Julian, et al. 2017.

HIV-associated periodontal diseases, along with oral infections, are considered serious complications of HIV. The incidence of periodontal infections in patients with HIV is lower than the incidence of oral infections Ryder, et al. 2012, but the increasing severity of periodontal diseases in the aging population of patients with HIV is a concern. Thus, there is a need to closely monitor these populations for the worsening of periodontal conditions Ryder, et al. 2020; Groenewegen, et al. 2019.

Management of periodontal lesions in patients with HIV has changed little in the past 30 years Goncalves, et al. 2013; Ryder, et al. 2012. Basic periodontal therapy provided at regular periodic intervals can effectively reduce periodontal inflammation in HIV patients Valentine, et al. 2016. Removal of local irritants from the root surfaces, mechanical debridement of necrotic tissues, and appropriate use of local and systemic antibiotics remain essential components of the management of HIV-associated gingival and periodontal diseases. The interaction between bacteria and Candida may play a vital role in the etiology of periodontal lesions; therefore, the management of HIV-associated periodontal lesions involves treating both bacteria and fungi Pihlstrom, et al. 2005. Multiple factors affect response to treatment, including immune status and personal oral hygiene practices of keeping the mouth, gums, and teeth clean Alpagot, et al. 2004.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Linear Gingival Erythema (LGE)

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

LGE Treatment

|

Presentation and Diagnosis

LGE characteristically presents as a distinct 2- to 3-mm-wide linear erythematous band limited to the free gingival margin (see Appendix: Photo- and Radiographs of Periodontal Disease Associated With HIV for images).

LGE typically presents at the anterior teeth initially Cherry-Peppers, et al. 2003, with subsequent progression to the posterior dentition Ryder, et al. 2012. Clinically, it may be difficult to distinguish LGE from severe gingivitis in patients with poor plaque control. LGE lesions do not resolve or respond to conventional periodontal therapy, including plaque control, scaling, and root planing. Initial biopsy is not indicated for diagnosis unless the tissue does not heal after follow-up because no microscopic appearance specific to LGE exists. X-rays may be used to rule out alveolar bone involvement.

| KEY POINT |

|

LGE is classified as a gingival disease of fungal origin by the American Academy of Periodontology because Candida is the primary etiological factor Armitage 1999. LGE lesions often resolve with topical and/or systemic antifungal treatment. Data are unavailable to establish whether LGE will evolve into a more severe form of periodontal disease; however, LGE may be a predecessor to the necrotizing ulcerative periodontal diseases that present in some patients with HIV Goncalves, et al. 2013. If LGE lesions do not resolve after 1 month of therapy, a biopsy may then help indicate a different diagnosis Ryder, et al. 2012.

Treatment

Conventional periodontal therapy does not adequately treat LGE, likely because of the presence of yeast within the gingival tissues Patton 2000; Candida is the etiological factor. Treatment for LGE includes oral hygiene instructions and mechanical supragingival debridement using minimal pressure on soft tissue to remove plaque Herrera, et al. 2014. Oral antimicrobial rinses are effective in treating LGE. As a first-line treatment, patients should rinse twice daily with a 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate suspension (a broad-spectrum oral antimicrobial) and be re-examined after 2 weeks. If lesions are persistent, topical antifungal medications can be used Cherry-Peppers, et al. 2003.

Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis and Necrotizing Ulcerative Periodontitis (NUG/NUP)

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

NUG/NUP Treatment

NUG/NUP Follow-Up

|

NUG and NUP are periodontal conditions that may be present in patients who do not have HIV, but both are more commonly associated with HIV and other systemic conditions Bodhade, et al. 2011.

Because of their similar clinical appearance and treatment, most studies have tended to classify NUG and NUP together as necrotizing periodontal lesions. Additionally, Candida organisms may be present in the tissues of NUP sites among patients with HIV, which suggests that Candida may have a role in HIV-associated NUP. Because of the presence of Candida in both LGE and NUG/NUP lesions, the possibility exists that LGE is a precursor to the development of NUG/NUP lesions. NUG and NUP are considered to be on the spectrum of the same pathologic process Ryder, et al. 2012; Bodhade, et al. 2011; Patton and McKaig 1998; Robinson, et al. 1998; hence, early diagnosis and intervention will be effective in treating necrotizing periodontal diseases.

Presentation and Diagnosis

NUG, formerly referred to as acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (ANUG), characteristically presents as a rapid onset of ulcerations of the interdental papilla with gingival bleeding and severe pain. Lesions are typically described as having a “punched out” appearance of the papilla, and the affected tissue appears to be covered with a fibrinous pseudomembrane (see Appendix: Photo- and Radiographs of Periodontal Disease Associated With HIV for images). Biopsy is not initially indicated for diagnosis unless the tissue does not show evidence of healing.

NUP lesions are similar in appearance to NUG lesions; however, NUP lesions extend into and destroy the alveolar bone. Patients with NUP frequently present with exposed bone, gingival recession, and tooth mobility. These clinical signs and symptoms do not necessarily involve the entire periodontium; only localized areas of the tooth-bearing bone and associated soft tissues may be affected. NUP is characterized by rapid destruction of bone that often leads to tooth loss, severe deep jaw pain, widespread soft tissue necrosis, bleeding, and fetid mouth odor. Other signs and symptoms of NUG and NUP include swelling of the regional lymph nodes, fever, and malaise. These clinical findings do not present in all patients and are considered secondary presentations of disease. The presence of NUP may be indicative of severe or worsening immunosuppression Ryder, et al. 2012; Bodhade, et al. 2011.

Treatment

Treatment initiation as soon as possible following the diagnosis of acute NUG/NUP is important to alleviate pain and tissue destruction. The well-established standard of care for NUG/NUP treatment by the oral health care provider includes debridement of infected areas; scaling and root planing of the teeth as needed; and intrasulcular lavage/irrigation with either 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate or, as an alternative, 10% povidone-iodine Herrera, et al. 2014. This standard of care is based on the principle of eliminating or reducing the microbial load by mechanically removing debris and plaque Hofer, et al. 2002. Such practices have been rigorously used over many years in the management of periodontal diseases in patients with HIV Ryder, et al. 2012; Mealey 1996; Holmstrup and Westergaard 1994; Winkler, et al. 1989. In severe cases or nonresponding conditions, systemic antimicrobials should be used as an adjunct to standard treatment Herrera, et al. 2014. Because the use of prophylactic antibiotic therapy might risk candidiasis Herrera, et al. 2014; Mealey 1996, the best option for antimicrobial therapy is metronidazole with an antifungal agent to prevent the development of a secondary manifestation of oral candidiasis. Once the acute disease is under control, definitive treatment, such as scaling and root planning as needed and therapy for pre-existing gingivitis or periodontitis, should be provided. These include adequate therapy for the pre-existing gingivitis or periodontitis, instructions on adequate oral hygiene practices at home, and supportive therapy such as periodontal recall maintenance Herrera, et al. 2014; Hofer, et al. 2002.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are effective for the treatment of periodontal diseases in patients with HIV Murray 1994. Follow-up treatment includes daily antimicrobial rinses and systemic antibiotics, specifically metronidazole 250 mg 3 times per day, for 7 to 14 days. Metronidazole is effective as an adjunct systemic antibiotic for treating periodontal diseases in patients with HIV Winkler and Robertson 1992. If the patient cannot tolerate metronidazole, clindamycin 150 mg 4 times per day or amoxicillin-clavulanate 875 mg twice per day for 7 to 10 days may be prescribed. Extraction of affected teeth may be necessary if the bone loss is severe. The use of systemic antibiotics increases the patient’s risk of developing candidiasis; therefore, concurrent, empiric administration of an antifungal agent should be considered to maintain the balance between treatment and potential negative side effects Ryder 2000.

During the acute and healing stages of NUP, frequent recall visits are needed to administer the necessary periodontal therapies, assess tissue response, and monitor the patient’s oral hygiene performance. Periodontal maintenance is generally indicated every 3 months once the infection is controlled Ryder, et al. 2012.

Favorable treatment responses to HIV-associated periodontal disease usually occur when the disease is addressed as early as possible Ryder, et al. 2012. Patients treated for NUP may develop repeated episodes, especially when oral hygiene practices are not good. NUP can be insidious, localized, and not necessarily related to plaque. Once clinical stabilization has occurred, visits every 3 months will allow for the detection and prevention of disease recurrence at an incipient stage Ryder, et al. 2012.

Necrotizing Ulcerative Stomatitis and Necrotizing Stomatitis (NUS/NS)

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

NUS/NS Treatment

|

Presentation and Diagnosis

Necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis and necrotizing stomatitis (NUS/NS) may be an extension of NUP into the adjacent supporting bone, leading to osteonecrosis and subsequent sequestration of the surrounding bone.

Patients may present with pronounced residual soft tissue and bony defects in the affected areas following treatment and healing of the necrotic tissues Ryder, et al. 2012; Armitage 1999; Horning and Cohen 1995. If the tissue does not heal, a soft tissue biopsy is indicated to exclude other potential diagnoses, such as the increased risk of cancer in patients with HIV Chen, et al. 2015.

When the soft tissue destruction is no longer contained to the soft tissue and bone of the oral cavity, this condition can be clinically consistent with Noma disease (also referred to as cancrum oris), which is more often seen in the pediatric population and is associated with severe or life-threatening malnourishment Feller, et al. 2014.

Treatment

| PERIODONTAL DISEASE PRESCRIPTION DOSING |

|

Broad-spectrum antibiotics are effective for the treatment of periodontal diseases in patients with HIV Patton and McKaig 1998; Murray 1994. Metronidazole is very effective as an adjunct systemic antibiotic for treating periodontal diseases in patients with HIV Winkler and Robertson 1992. Metronidazole is effective against gram-negative bacteria that are typically involved in periodontal diseases. Augmentin can be used as an alternative if a patient has gastrointestinal problems with metronidazole. Both 0.12% chlorhexidine gluconate and 10% povidone-iodine are effective treatment modalities, and either may be used in office and at home as an antimicrobial rinse Hofer, et al. 2002. A local anesthetic may be indicated for pain management during the removal of necrotic debris, scaling, and root planing.

Chronic Pre-Existing Periodontal Disease

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Chronic Pre-Existing Periodontal Disease Treatment

|

Presentation and Diagnosis

About half of the U.S. population >30 years of age is affected by chronic periodontal disease, and the prevalence of periodontal disease increases with age Eke, et al. 2015. No data currently exist to indicate the extent to which HIV infection may accelerate the destruction of periodontal tissues in the population with HIV. However, the occurrence of rapid attachment loss may indicate severe immunosuppression Ryder, et al. 2012; Mealey 1996. Pre-existing periodontal disease can be diagnosed by clinical characteristics and radiographic examination for bone loss as recommended by the American Academy of Periodontology American Academy of Periodontology 2000; Armitage 1999. The clinical characteristics for chronic periodontitis include the presence of periodontal pockets, clinical attachment loss, and bleeding on probing. Radiographic analysis can reveal the presence of periodontal bone loss with horizontal or vertical bony defects. Increased mobility of teeth may also be observed in association with clinical attachment loss and bone loss.

Treatment

Scaling and root planing is recommended for nonsurgical treatment of periodontal disease American Academy of Periodontology 2000. A recent case-control study further reinforced that nonsurgical periodontal therapy has a beneficial effect on clinical and immunological parameters of chronic periodontitis, reduction of oral Candida counts, and improvement of HIV infection status. Patients with chronic periodontitis treated with nonsurgical periodontal therapy had an increase in CD4+ T-lymphocytes and a reduction in viral load Nobre, et al. 2019.

Surgical therapy, including flap debridement and extraction of teeth, can be performed without postoperative complications. Before surgical treatment, consultation with the patient’s physician may be indicated to obtain information regarding hematological levels of immune cells. Low neutrophil counts may indicate the adjunct use of systemic antimicrobial therapy.

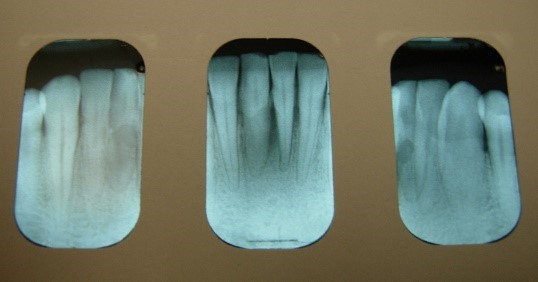

Appendix: Photo- and Radiographs of Periodontal Disease Associated With HIV

Photographs courtesy of Dr. Gwen Cohen Brown and the Dental Hygiene Department of New York City College of Technology

Figure 1: Patient with linear gingival erythema (LGE)

Figure 2: Patient with necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP)

Figure 3: Patient with linear gingival erythema (LGE) and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP)

Figure 4: Patient with linear gingival erythema (LGE) and necrotizing ulcerative periodontitis (NUP)

Figure 5: Patient with necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis (NUG)

Figure 6: Patient with localized bone loss

Figure 7: Patient with localized bone loss

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS: MANAGEMENT OF PERIODONTAL DISEASE |

LGE Treatment

NUG/NUP Treatment

NUG/NUP Follow-Up

NUS/NS Treatment

Chronic Pre-Existing Periodontal Disease Treatment

|

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

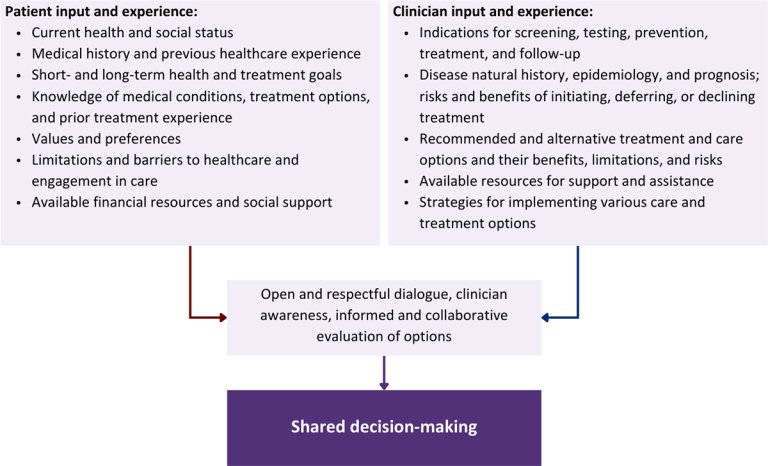

Rationale

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Alpagot T., Duzgunes N., Wolff L. F., et al. Risk factors for periodontitis in HIV patients. J Periodontal Res 2004;39(3):149-57. [PMID: 15102043]

American Academy of Periodontology. Parameters of care. American Academy of Periodontology. J Periodontol 2000;71(5 Suppl):i-ii, 847-83. [PMID: 11032511]

Armitage G. C. Development of a classification system for periodontal diseases and conditions. Ann Periodontol 1999;4(1):1-6. [PMID: 10863370]

Baccaglini L., Atkinson J. C., Patton L. L., et al. Management of oral lesions in HIV-positive patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2007;103 Suppl:S50.e1-23. [PMID: 17379155]

Bodhade A. S., Ganvir S. M., Hazarey V. K. Oral manifestations of HIV infection and their correlation with CD4 count. J Oral Sci 2011;53(2):203-11. [PMID: 21712625]

Chen C. H., Chung C. Y., Wang L. H., et al. Risk of cancer among HIV-infected patients from a population-based nested case-control study: implications for cancer prevention. BMC Cancer 2015;15:133. [PMID: 25885746]

Cherry-Peppers G., Daniels C. O., Meeks V., et al. Oral manifestations in the era of HAART. J Natl Med Assoc 2003;95(2 Suppl 2):21s-32s. [PMID: 12656429]

Eke P. I., Dye B. A., Wei L., et al. Update on prevalence of periodontitis in adults in the United States: NHANES 2009 to 2012. J Periodontol 2015;86(5):611-22. [PMID: 25688694]

Feller L., Altini M., Chandran R., et al. Noma (cancrum oris) in the South African context. J Oral Pathol Med 2014;43(1):1-6. [PMID: 23647162]

Goncalves L. S., Goncalves B. M., Fontes T. V. Periodontal disease in HIV-infected adults in the HAART era: clinical, immunological, and microbiological aspects. Arch Oral Biol 2013;58(10):1385-96. [PMID: 23755999]

Griffen A. L., Thompson Z. A., Beall C. J., et al. Significant effect of HIV/HAART on oral microbiota using multivariate analysis. Sci Rep 2019;9(1):19946. [PMID: 31882580]

Groenewegen H., Bierman W. F. W., Delli K., et al. Severe periodontitis is more common in HIV- infected patients. J Infect 2019;78(3):171-77. [PMID: 30528870]

Herrera D., Alonso B., de Arriba L., et al. Acute periodontal lesions. Periodontol 2000 2014;65(1):149-77. [PMID: 24738591]

Hofer D., Hammerle C. H., Grassi M., et al. Long-term results of supportive periodontal therapy (SPT) in HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative patients. J Clin Periodontol 2002;29(7):630-37. [PMID: 12354088]

Holmstrup P., Westergaard J. Periodontal diseases in HIV-infected patients. J Clin Periodontol 1994;21(4):270-80. [PMID: 8195444]

Horning G. M., Cohen M. E. Necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, periodontitis, and stomatitis: clinical staging and predisposing factors. J Periodontol 1995;66(11):990-98. [PMID: 8558402]

Kaplan J. E., Benson C., Holmes K. K., et al. Guidelines for prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from CDC, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep 2009;58(Rr-4):1-207; quiz CE1-4. [PMID: 19357635]

Mataftsi M., Skoura L., Sakellari D. HIV infection and periodontal diseases: an overview of the post-HAART era. Oral Dis 2011;17(1):13-25. [PMID: 21029260]

Mealey B. L. Periodontal implications: medically compromised patients. Ann Periodontol 1996;1(1):256-321. [PMID: 9118261]

Moscicki A. B., Yao T. J., Russell J. S., et al. Biomarkers of oral inflammation in perinatally HIV-infected and perinatally HIV-exposed, uninfected youth. J Clin Periodontol 2019;46(11):1072-82. [PMID: 31385616]

Murray P. A. Periodontal diseases in patients infected by human immunodeficiency virus. Periodontol 2000 1994;6:50-67. [PMID: 9673170]

Nobre A. V., Polvora T. L., Silva L. R., et al. Effects of non-surgical periodontal therapy on clinical and immunological profile and oral colonization of Candida spp in HIV-infected patients with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol 2019;90(2):167-76. [PMID: 30118537]

Noguera-Julian M., Guillen Y., Peterson J., et al. Oral microbiome in HIV-associated periodontitis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(12):e5821. [PMID: 28328799]

Ntolou P., Pani P., Panis V., et al. The effect of antiretroviral therapyon the periodontal conditions of patients with HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 2023;50(2):170-82. [PMID: 36261851]

Patton L. L. Sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value of oral opportunistic infections in adults with HIV/AIDS as markers of immune suppression and viral burden. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2000;90(2):182-88. [PMID: 10936837]

Patton L. L., McKaig R. Rapid progression of bone loss in HIV-associated necrotizing ulcerative stomatitis. J Periodontol 1998;69(6):710-16. [PMID: 9660340]

Pihlstrom B. L., Michalowicz B. S., Johnson N. W. Periodontal diseases. Lancet 2005;366(9499):1809-20. [PMID: 16298220]

Polvora T. L., Nobre A. V., Tirapelli C., et al. Relationship between human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1) infection and chronic periodontitis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2018;14(4):315-27. [PMID: 29595347]

Robinson P. G., Sheiham A., Challacombe S. J., et al. Gingival ulceration in HIV infection. A case series and case control study. J Clin Periodontol 1998;25(3):260-67. [PMID: 9543197]

Ryder M. I. Periodontal management of HIV-infected patients. Periodontol 2000 2000;23:85-93. [PMID: 11276769]

Ryder M. I., Nittayananta W., Coogan M., et al. Periodontal disease in HIV/AIDS. Periodontol 2000 2012;60(1):78-97. [PMID: 22909108]

Ryder M. I., Shiboski C., Yao T. J., et al. Current trends and new developments in HIV research and periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000 2020;82(1):65-77. [PMID: 31850628]

Stabholz A., Soskolne W. A., Shapira L. Genetic and environmental risk factors for chronic periodontitis and aggressive periodontitis. Periodontol 2000 2010;53:138-53. [PMID: 20403110]

Toljic B., Trbovich A. M., Petrovic S. M., et al. Ageing with HIV - a periodontal perspective. New Microbiol 2018;41(1):61-66. [PMID: 29505065]

Valentine J., Saladyanant T., Ramsey K., et al. Impact of periodontal intervention on local inflammation, periodontitis, and HIV outcomes. Oral Dis 2016;22 Suppl 1:87-97. [PMID: 27109277]

Winkler J. R., Murray P. A., Grassi M., et al. Diagnosis and management of HIV-associated periodontal lesions. J Am Dent Assoc 1989;Suppl:25s-34s. [PMID: 2531767]

Winkler J. R., Robertson P. B. Periodontal disease associated with HIV infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1992;73(2):145-50. [PMID: 1532235]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines | |

| Date of original publication | March 08, 2017 |

| Date of current publication | April 12, 2023 |

| Highlights of changes, additions, and updates in the April 12, 2023 edition |

Reviewed and determined to be up to date. |

| Intended users | New York State clinicians who provide dental care for adults with HIV |

| Lead author |

Abhiram Maddi, PhD, MS, DDS |

| Contributing author |

Stephen N. Abel, DDS, MSD |

| Writing group |

Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona Vail, MD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

| Related NYSDOH AI guidelines |

N/A |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on January 18, 2024