Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: November 4, 2024

Lead author: Sangyoon Jason Shin, DO

Writing group: Rona M. Vail, MD, AAHIVS; Sanjiv S. Shah, MD, MPH, AAHIVM, AAHIV; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD, FACP, AAHIVS; Jessica Rodrigues, MPH, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Brianna L. Norton, DO, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: November 16, 2021

This guideline was developed by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) to assist clinicians in perioperative care management for adults with HIV, which is largely the same as for adults without HIV. The guideline focuses on concerns specific to patients with HIV. The goals of this guideline are to:

- Make clear that HIV is not a contraindication to surgery.

- Advise that HIV does not increase surgical risk in virally suppressed patients and that HIV transmission to the surgical team is eliminated in virally suppressed patients.

- Provide guidance for managing risks of elective surgery in patients who are not virally suppressed.

- Emphasize that interruptions in antiretroviral therapy and opportunistic infection prophylaxis or treatment should be avoided.

The guideline is intended to supplement, not replace, routinely used perioperative protocols that cover stabilization of active medical conditions and risk stratification.

Note on “experienced” HIV care providers: The NYSDOH AI Clinical Guidelines Program defines an “experienced HIV care provider” as a practitioner who has been accorded HIV Specialist status by the American Academy of HIV Medicine. Nurse practitioners (NPs) and licensed midwives who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV in collaboration with a physician may be considered experienced HIV care providers if all other practice agreements are met; NPs with more than 3,600 hours of qualifying experience do not require collaboration with a physician (8 NYCRR 79-5:1; 10 NYCRR 85.36; 8 NYCRR 139-6900). Physician assistants who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV under the supervision of an HIV Specialist physician may also be considered experienced HIV care providers (10 NYCRR 94.2).

HIV-Specific Perioperative Considerations

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Emergency and Urgent Surgery

Elective Surgery: Determine HIV Clinical Status

Continue HIV Medications

Evaluate for Potential Drug-Drug Interactions

|

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; OI, opportunistic infection; PI, protease inhibitor. Note:

|

| KEY POINTS |

|

Emergency and Urgent Surgery

Consistent with operative standards of care, emergency and urgent surgeries should not be delayed in patients with HIV for preoperative evaluation and risk stratification, including CD4 count and HIV viral load testing. CD4 count testing can often take many days to complete.

Elective Surgery: Determine HIV Clinical Status

Preoperative evaluation: All standard preoperative assessments should be performed in patients with HIV, including cardiovascular and pulmonary evaluations such as the Revised Cardiac Risk Index (RCRI) and the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) Surgical Risk Calculator scores. Individuals with HIV tend to have earlier and more comorbidities than those without HIV, including coronary artery disease, thromboembolic events, and pulmonary complications. As with all patients, a detailed assessment of social support, housing, and food security is required to determine the level of assistance needed for optimal postoperative recovery.

In patients with HIV, clinicians should review the most recent CD4 cell count and HIV viral load test results as part of the preoperative evaluation. If recent test results (6 months for HIV viral load; 12 months for CD4 count) are available in the patient’s medical records, retesting before surgery is unnecessary. For most individuals taking ART, the current recommendation is to perform CD4 count testing every 12 months if a patient’s CD4 count is ≤350 cells/mm3 and HIV viral load testing at least every 6 months. In those with viral suppression and a CD4 count >350 cells/mm3, CD4 count monitoring is optional.

If records indicate that a patient has undetectable HIV RNA but has not had recent CD4 count testing, a CD4 count can be ordered, though it is not necessary and should not delay surgery. If no records are available, preoperative CD4 count and HIV viral load tests should be ordered. Other laboratory test results to consider for patients with HIV include complete blood count with differential and basic metabolic panel Smetana and Macpherson 2003.

| KEY POINT |

|

Risk factors for surgical complications: In general, in patients with HIV, the combination of a low CD4 count and an uncontrolled viral load is associated with an increased risk of postoperative mortality and complications. If surgery is elective and the patient has a viral load level ≥200 copies/mL or CD4 count ≤200 cells/mm3, clinicians should consult with the patient’s primary care provider or an experienced HIV care provider.

Several studies have shown that a diagnosis of AIDS (CD4 count ≤200 cells/mm3) is associated with increased postoperative mortality Sandler, et al. 2019; Gahagan, et al. 2016; King, et al. 2015; Naziri, et al. 2015; Horberg, et al. 2006. This finding was consistent across multiple sites for emergency general surgery Sandler, et al. 2019, total hip arthroplasty Naziri, et al. 2015, and all types of surgery at a Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program in Northern California Horberg, et al. 2006.

One study found a slightly higher mortality rate among people with controlled HIV (CD4 count >200 cells/mm3) compared to those without HIV King, et al. 2015, but 2 studies found no increased mortality Sandler, et al. 2019; Gahagan, et al. 2016. In a systematic review and pooled analysis of outcomes after cardiac surgery, investigators found that mortality in patients with HIV was similar to that in those without HIV (odds ratio 0.89, 95% confidence interval 0.72-1.12, P = 0.32) Dominici and Chello 2020. Evidence is mixed on an association between low CD4 count and postoperative complications, such as infections and poor wound healing Zhao, et al. 2021; Lin, et al. 2020; Sandler, et al. 2019; Sharma, et al. 2018; Guild, et al. 2012; Cacala, et al. 2006; Horberg, et al. 2006; Tran, et al. 2000. One study found that a viral load >30,000 copies/mL, but not CD4 count, was associated with an increased risk of surgical complications Horberg, et al. 2006.

The results of these studies can be difficult to interpret because the studies were conducted during different periods, and most did not evaluate the effect of HIV RNA level. However, the evidence points to an increased risk of surgical complications in patients with HIV who have low CD4 counts, almost certainly in combination with viremia and AIDS-related comorbidities.

Not all patients with HIV RNA levels ≥200 copies/mL and CD4 count ≤200 cells/mm3 are at increased risk of surgical complications. Some patients may have stable, low-level viremia and additional time on ART or changing the ART regimen is unlikely to reduce the viral load or change clinical stability. For these patients, it is reasonable for surgery to proceed. Input from the patient’s primary care doctor or an experienced HIV care provider is essential to help guide this decision. Other patients who are taking ART may have an undetectable HIV viral load for many years but have incomplete immune reconstitution, and therefore low CD4 counts. In this circumstance, delaying surgery is unlikely to lead to CD4 count recovery.

If initiating or changing ART has the potential to reduce the risk of surgical complications, clinicians should engage the patient in shared decision-making regarding the risks and benefits of delaying elective surgery long enough to initiate or adjust ART. The decision to delay surgery involves nuance and a balance of risks and benefits for the individual patient. Factors to consider include the patient’s clinical stability defined by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status Classification system, purpose of surgery (emergency vs. elective), risk of delaying surgical intervention, likelihood that the patient will return for surgery, and likelihood that the patient’s clinical status will improve during the delay.

If patients are not taking ART, clinicians should refer them to an HIV care provider who can initiate ART. If a patient has a high viral load and low CD4 count and chooses not to take or change ART, clinicians should explain the potential risk of surgical complications and engage the patient in a discussion of the risks and benefits of planned elective surgery.

Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis: As noted above, evidence is mixed regarding an association between lower CD4 count and postoperative infections. Some studies found a positive association in multiple types of surgeries Sandler, et al. 2019; Liu, et al. 2012; Zhang, et al. 2012; Tran, et al. 2000 and orthopedic traumas Zhao, et al. 2021; Guild, et al. 2012, while others found no association across multiple types of surgeries Cacala, et al. 2006, including total hip arthroplasties Lin, et al. 2020. One study found that higher viral loads, but not low CD4 cell counts, were associated with postoperative complications, including infections across multiple types of surgery Horberg, et al. 2006. Taken together, the evidence suggests that use of pre-operative antibiotic prophylaxis is reasonable in patients with low CD4 cell counts or high viral loads to decrease the chance of postoperative surgical site infections and sepsis.

Continue HIV Medications

ART and OI prophylaxis should be continued throughout the perioperative period, especially in patients with HIV/hepatitis B virus (HBV) coinfection in whom cessation of ART can lead to an HBV flare Perrillo 2001. If patients have difficulty swallowing or nasogastric tubes, clinicians can offer equivalent doses of ART in liquid formulations or pediatric pill sizes and advise patients which ART medications can be crushed. For all forms of ART (oral, injection, infusion), the timing of elective surgery should be coordinated with the timing of ART administration to avoid missed doses.

If a patient cannot eat or drink due to the surgical procedure and ART interruption is necessary, all medications in the regimen should be held. If a patient is taking prophylaxis for HIV-related OIs, clinicians should consult an infectious disease specialist if medication interruption or dosing adjustments are required.

Evaluate for Drug-Drug Interactions With Antiretroviral Medications

There is increased potential for drug-drug interactions in patients taking ART due to cytochrome P450 interactions with PIs, NNRTIs, and regimens boosted with ritonavir or cobicistat. Table 1, below, lists common perioperative medications that may interact with ART. It is essential to check up-to-date resources for potential interactions (see Resources: HIV Drug-Drug Interactions, below) or consult with an experienced HIV care provider. If there is an unavoidable drug-drug interaction, clinicians should consult an experienced HIV care provider before surgery to plan medication management and dosing.

| Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; AUC, area under the curve; CYP3A4, cytochrome P450 3A4; CYP450, cytochrome P450; FDA, U.S. Food and Drug Administration; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; P-gP, P-glycoprotein; PI, protease inhibitor; QTc, corrected QT interval.

Notes:

|

|

| Table 1: Potential Drug-Drug Interactions Between Medications Commonly Used in Perioperative Management and Antiretroviral Agents (also see drug package inserts) | |

| Perioperative Medication or Class | Antiretroviral Medication or Class |

| Anesthetics [a] | |

| Fentanyl |

|

| Lidocaine |

|

| Paralytics and Reversal Agents [c] | |

| Rocuronium |

|

| Sedatives | |

| Haloperidol | See NYSDOH AI resource Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From HIV Prevention to Treatment > Antipsychotics. |

| Midazolam |

|

| Olanzapine |

|

| Miscellaneous short-acting antipsychotics (risperidone, ziprasidone, quetiapine) |

|

| Miscellaneous, Other | |

| Ondansetron | No interactions expected. No dose adjustment required. |

| Acid-reducing agents | See NYSDOH AI resource Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From HIV Prevention to Treatment > Acid-Reducing Agents. |

| Anticoagulants | See NYSDOH AI resource Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From HIV Prevention to Treatment > Anticoagulants. |

| Non-opioid analgesics | See NYSDOH AI resource Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From HIV Prevention to Treatment > Nonopioid Pain Medications for potential interactions between NSAIDs and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate. |

| Opioid analgesics | See NYSDOH AI resource Drug-Drug Interaction Guide: From HIV Prevention to Treatment > Opioid Analgesics and Tramadol. |

| RESOURCES |

|

Manage Postoperative Care

There is a greater risk of venous thrombosis in patients with HIV than those without HIV Bala, et al. 2016; Malek, et al. 2011; Shen and Frenkel 2004. Thus, it is essential to mobilize patients with HIV as soon as medically feasible after surgery; for patients at moderate risk of venous thrombosis, mechanical/pharmacologic prophylaxis can be initiated Gould, et al. 2012. People with a long history of HIV, low CD4 count, or exposure to boosted regimens and glucocorticoids are at increased risk of hypoadrenalism, which the stress of surgery can unmask Makaram, et al. 2018. This possibility should be considered in assessing postoperative hypotension.

In patients with HIV and postoperative fever, common causes of fever, including urinary tract infections, pneumonia, venous thromboembolism, wound infections, or Clostridioides difficile if antibiotics were administered, should be considered before HIV-related causes. If the patient has a CD4 count ≤200 cells/mm3, clinicians should consult an infectious disease specialist and consider OIs.

If ART or OI prophylaxis is discontinued, clinicians should ensure the patient restarts the medication(s) as soon as possible.

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS |

Emergency and Urgent Surgery

Elective Surgery: Determine HIV Clinical Status

Continue HIV Medications

Evaluate for Potential Drug-Drug Interactions

|

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; OI, opportunistic infection; PI, protease inhibitor. Note:

|

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

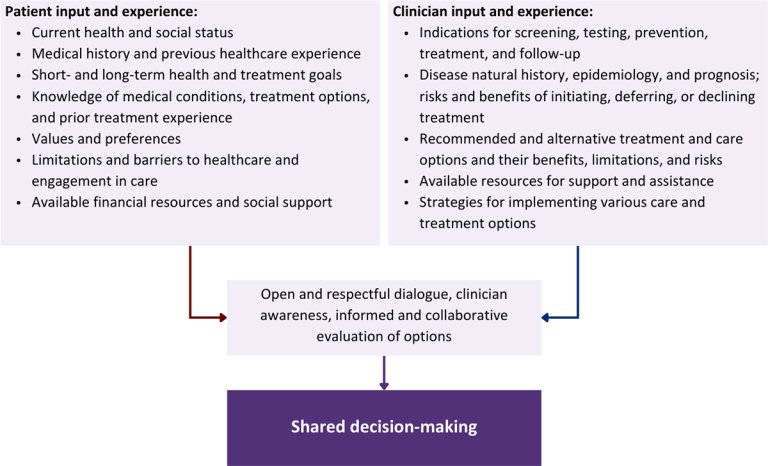

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Bala A., Penrose C. T., Visgauss J. D., et al. Total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with HIV infection: complications, comorbidities, and trends. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2016;25(12):1971-79. [PMID: 27117043]

Cacala S. R., Mafana E., Thomson S. R., et al. Prevalence of HIV status and CD4 counts in a surgical cohort: their relationship to clinical outcome. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2006;88(1):46-51. [PMID: 16460640]

Dominici C., Chello M. Impact of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: a systematic review. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2020;21(3):411-18. [PMID: 33070545]

Gahagan J. V., Halabi W. J., Nguyen V. Q., et al. Colorectal surgery in patients with HIV and AIDS: trends and outcomes over a 10-year period in the USA. J Gastrointest Surg 2016;20(6):1239-46. [PMID: 26940943]

Gould M. K., Garcia D. A., Wren S. M., et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2012;141(2 Suppl):e227S-77S. [PMID: 22315263]

Guild G. N., Moore T. J., Barnes W., et al. CD4 count is associated with postoperative infection in patients with orthopaedic trauma who are HIV positive. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470(5):1507-12. [PMID: 22207561]

Horberg M. A., Hurley L. B., Klein D. B., et al. Surgical outcomes in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Arch Surg 2006;141(12):1238-45. [PMID: 17178967]

Joyce M. P., Kuhar D., Brooks J. T. Notes from the field: occupationally acquired HIV infection among health care workers - United States, 1985-2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2015;63(53):1245-46. [PMID: 25577991]

King J. T., Perkal M. F., Rosenthal R. A., et al. Thirty-day postoperative mortality among individuals with HIV infection receiving antiretroviral therapy and procedure-matched, uninfected comparators. JAMA Surg 2015;150(4):343-51. [PMID: 25714794]

Lin C. A., Behrens P. H., Paiement G., et al. Metabolic factors and post-traumatic arthritis may influence the increased rate of surgical site infection in patients with human immunodeficiency virus following total hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Surg Res 2020;15(1):316. [PMID: 32787972]

Liu B., Zhang L., Guo R., et al. Anti-infective treatment in HIV-infected patients during perioperative period. AIDS Res Ther 2012;9(1):36. [PMID: 23181440]

Makaram N., Russell C. D., Roberts S. B., et al. Exogenous steroid-induced hypoadrenalism in a person living with HIV caused by a drug-drug interaction between cobicistat and intrabursal triamcinolone. BMJ Case Rep 2018;11(1):e226912. [PMID: 30567264]

Malek J., Rogers R., Kufera J., et al. Venous thromboembolic disease in the HIV-infected patient. Am J Emerg Med 2011;29(3):278-82. [PMID: 20825798]

Naziri Q., Boylan M. R., Issa K., et al. Does HIV infection increase the risk of perioperative complications after THA? A nationwide database study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015;473(2):581-86. [PMID: 25123240]

Perrillo R. P. Acute flares in chronic hepatitis B: the natural and unnatural history of an immunologically mediated liver disease. Gastroenterology 2001;120(4):1009-22. [PMID: 11231956]

Sandler B. J., Davis K. A., Schuster K. M. Symptomatic human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients have poorer outcomes following emergency general surgery: a study of the nationwide inpatient sample. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2019;86(3):479-88. [PMID: 30531208]

Sharma G., Strong A. T., Boules M., et al. Comparative outcomes of bariatric surgery in patients with and without human immunodeficiency virus. Obes Surg 2018;28(4):1070-79. [PMID: 29127578]

Shen Y. M., Frenkel E. P. Thrombosis and a hypercoagulable state in HIV-infected patients. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2004;10(3):277-80. [PMID: 15247986]

Smetana G. W., Macpherson D. S. The case against routine preoperative laboratory testing. Med Clin North Am 2003;87(1):7-40. [PMID: 12575882]

Tran H. S., Moncure M., Tarnoff M., et al. Predictors of operative outcome in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Surg 2000;180(3):228-33. [PMID: 11084136]

Zhang L., Liu B. C., Zhang X. Y., et al. Prevention and treatment of surgical site infection in HIV-infected patients. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:115. [PMID: 22583551]

Zhao R., Ding R., Zhang Q. What are the risk factors for surgical site infection in HIV-positive patients receiving open reduction and internal fixation of traumatic limb fractures? A retrospective cohort study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 2021;37(7):551-56. [PMID: 33386058]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Resources | |

| Date of original publication | November 16, 2021 |

| Date of current publication | November 04, 2024 |

| Highlights of changes, additions, and updates in the November 04, 2024 edition |

|

| Intended users | New York State clinicians who provide perioperative care for adults with HIV |

| Lead author |

Sangyoon Jason Shin, DO |

| Writing group |

Rona M. Vail, MD, AAHIVS; Sanjiv S. Shah, MD, MPH, AAHIVM, AAHIV; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD, FACP, AAHIVS; Jessica Rodrigues, MPH, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Brianna L. Norton, DO, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures. |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

| Related NYSDOH AI resources |

Guidelines

GuidancePodcast |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on October 8, 2025