Purpose of This Guidance

Date of current publication: October 11, 2023

Developed by the NYSDOH AIDS Institute’s Perinatal HIV Prevention Program, Office of Sexual Health & Epidemiology, and Office of the Medical Director

The questions and answers below are presented as guidance for clinicians in New York State who provide medical care for newborns and infants with perinatal HIV exposure. With 2 exceptions, the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) supports the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) recommendations for Diagnosis of HIV Infection in Infants and Children DHHS 2023. However, the NYSDOH AI strongly advises clinicians to 1) perform at-birth testing of all exposed infants, regardless of the assessed risk of HIV acquisition (DHHS recommends birth testing for high-risk exposures only); and 2) recognize fewer than 3 prenatal care visits as a criterion for high-risk exposure (DHHS considers 0 prenatal care visits high risk).

The goals of this guidance are to:

- Increase New York State clinicians’ awareness of the rationale for, benefits of, and best practices for at-birth HIV testing of all infants with perinatal exposure, while reinforcing DHHS recommendations in general

- Reinforce the procedure for confirmatory testing following a positive HIV test result

- Highlight the New York State criteria for high-risk perinatal HIV exposure

- Clarify the post-birth serial HIV testing schedule based on exposure risk and method of infant feeding

- Encourage New York State clinicians to use the free-of-charge pediatric HIV testing services at the Wadsworth Center and to seek consultation with an experienced HIV clinician through the Clinical Education Initiative (CEI) Line: 1-866-637-2342, option 2 (available 24/7)

Rationale: Perinatal HIV transmission continues. In New York State there were 20 perinatal HIV transmissions detected between 2010 and 2020; these infants were among the 4,599 born to 4,501 unique individuals diagnosed with HIV before or at the time of delivery. Approximately 70% (n=3,219) of the infants perinatally exposed to HIV received their first nucleic acid test (NAT) within 0 to 2 days after birth, 9% within 3 to 4 days after birth, and 14% more than 4 days after birth. HIV transmission was detected from specimens collected within 0 to 2 days after birth in 10 of 20 (53%) infants in whom HIV transmission was detected NYSDOH 2022.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiated as close to the time of birth as possible reduces the risk of HIV acquisition in perinatally exposed infants; the benefit of ART for newborns decreases when initiation is delayed Fiscus, et al. 1999; Wade, et al. 1998. Therefore, experts recommend initiating ART as promptly as possible after delivery and preferably within 6 hours of birth; see DHHS > Antiretroviral Management of Newborns With Perinatal HIV Exposure or HIV Infection.

HIV Testing at Birth

Q: When should clinicians perform the first HIV NAT in an infant perinatally exposed to HIV?

A: The DHHS recommends HIV testing at birth in infants with high-risk exposures and testing at 14 to 21 days after birth in infants with low-risk exposures. Risk refers to the risk that an infant will acquire HIV and is based on maternal factors explained below (see Box 1, below).

The NYSDOH AI strongly advocates for at-birth HIV testing for all infants perinatally exposed to HIV, regardless of the exposure risk.

Q: Why does the NYSDOH AI advocate testing at birth if an infant’s risk of HIV acquisition is low?

A: Birth testing provides an opportunity for timely HIV diagnosis in exposed infants.

Among the benefits of at-birth HIV testing is the immediate activation of New York State surveillance activities that ensure an infant’s linkage to care and address obstacles to follow-up, such as 1) infant/family relocation within and outside of New York State; 2) infant name change(s); 3) infant involvement with foster care and/or adoption services; and 4) factors, whether anticipated or unexpected, that impede a family’s ability to access care.

The NYSDOH AI asserts that facilitating timely HIV diagnosis and linkage to care are crucial for infants perinatally exposed to HIV and for their families or guardians.

Q: Is there an optimal time for collecting an infant’s specimen for HIV testing at birth?

A: Ideally, the specimen should be collected within 6 hours, before antiretroviral (ARV) prophylaxis is initiated; if it is impossible to obtain a specimen before ARV prophylaxis is initiated, the newborn’s specimen may be obtained for up to 48 hours after delivery.

The ideal sequence is to collect a specimen for HIV testing as soon as possible after birth, then initiate ARV prophylaxis. Early neonatal initiation of ARV prophylaxis is associated with a decline in HIV-1-infected cells and low or undetectable levels of HIV-1 RNA and DNA, which may delay HIV diagnosis.

The NYSDOH AI endorses the DHHS recommendation that ARV prophylaxis for exposed infants should be initiated as soon as possible after delivery, ideally within 6 hours of birth. Initiation of ARV prophylaxis should not be delayed by specimen collection and HIV testing.

Q: If a positive HIV NAT result is obtained at birth or at any time after, what is the procedure for confirming an HIV diagnosis in an exposed infant?

A: The procedure for confirmatory testing if an infant’s HIV nucleic acid test (NAT) result is positive at any age is to obtain a new specimen as quickly as possible and perform an HIV NAT using the new specimen. If a second positive HIV NAT result is obtained, no additional testing is required and a definitive diagnosis of HIV infection may be made.

Risk of Infant HIV Acquisition

Q: If HIV testing is performed in all exposed infants at birth in New York State, is it still important to assess an infant’s risk of HIV acquisition as high or low?

A: Yes. The number of serial HIV tests performed after the first test at birth is determined based on the infant’s risk of HIV acquisition. Infants at high risk are recommended to receive additional tests at critical timepoints.

Q: How are “low risk” and “high risk” defined with regard to an exposed infant’s risk of HIV acquisition?

A: The risk of an infant’s perinatal exposure to HIV is based on maternal factors and refers to the risk that the infant will acquire HIV as a result of the exposure.

Per the DHHS, infants are at low risk of HIV acquisition if born to mothers who received and were adherent to ART during pregnancy and who sustained an HIV RNA level (viral load) <50 copies/mL. The NYSDOH AI agrees with this definition.

Per the DHHS, infants are at high risk of HIV acquisition if born to mothers who meet any of the following criteria:

- No antepartum ARVs or only intrapartum ARVs

- ART initiated late in pregnancy (e.g., after week 20)

- Acute HIV diagnosis during pregnancy or labor

- HIV viral load ≥50 copies/mL close to the time of delivery (includes those who did not achieve viral suppression while taking ART)

- Fewer than 3 prenatal care visits per NYSDOH AI (0 prenatal care visits per DHHS)

| Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; ARV, antiretroviral medication; DHHS, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. | |

| Box 1: DHHS and NYSDOH AI Criteria for Low and High Risk of HIV Acquisition From Perinatal Exposure | |

| Low Risk | High Risk |

Per DHHS and NYSDOH AI: Infants at low risk of acquiring HIV from perinatal exposure are those born to mothers who:

|

Per DHHS and NYSDOH AI: Infants at high risk of acquiring HIV from perinatal exposure are those born to mothers who:

Per DHHS: Did not receive prenatal care Per NYSDOH AI: Had <3 prenatal care visits |

Recommendations for ARV Initiation in HIV-Exposed Infants

Q: Does the NYSDOH AI have a guideline on ARV initiation in infants perinatally exposed to HIV?

A: The NYSDOH AI endorses the DHHS recommendations in Antiretroviral Management of Newborns With Perinatal HIV Exposure or HIV Infection for all clinicians managing the care of infants diagnosed with or perinatally exposed to HIV.

Q: Is expert consultation required for infant ARV initiation?

A: Expert consultation is not required but is encouraged. When consultation would be helpful, New York State clinicians can consult with an HIV expert regarding maternal or fetal HIV exposure by calling the CEI Line: 1-866-637-2342, option 2 (available 24/7).

Expert Consultation

Q: Under what circumstances should a clinician consult with an expert in managing the medical care of an HIV-exposed infant?

A: Consultation with an experienced HIV care provider is especially helpful when there are maternal factors that may increase the risk of transmission. Such factors include but are not limited to:

- Primary or acute HIV during pregnancy

- Inconsistent adherence to ART

- HIV viral load ≥50 copies/mL

- Nonadherence to prenatal visits

- Undocumented HIV viral load within 4 weeks before delivery or undocumented HIV status at time of delivery

- Preliminary positive HIV test result during labor or shortly after delivery

- Intrapartum HIV prophylaxis not administered when indicated

- Diagnosis of acute or primary HIV infection in the breast/chest-feeding parent

- Expert consultation is also advised when considering:

- Administration of ARVs in addition to or instead of zidovudine for infant HIV prophylaxis

- Early discontinuation of infant HIV prophylaxis

- Indications for opportunistic infection prophylaxis in an infant diagnosed with HIV

CEI Line: New York State clinicians can consult an HIV expert 24/7 regarding maternal or fetal HIV exposure by calling the CEI Line: 1-866-637-2342, option 2.

National Perinatal Hotline: Clinicians outside of New York State can call the National Perinatal HIV Hotline 24/7: 1-888-448-8765.

Serial HIV Testing Schedule After the At-Birth Test

Q: Is there a set schedule for additional (serial) HIV testing in exposed infants after they are tested at birth?

A: Yes. Box 2, below, specifies the serial HIV testing schedule recommended by the DHHS for infants perinatally exposed to HIV and for infants with ongoing exposure to HIV through breast milk from a parent with HIV.

| Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; ARV, antiretroviral medication; NAT, nucleic acid test; PCP, Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (previously P. carinii pneumonia).

Notes:

|

||

| Box 2: New York State Age Intervals for HIV Nucleic Acid Testing in Infants With Perinatal and Ongoing HIV Exposure | ||

Ages for HIV NAT with low-risk exposure [a]:

|

Ages for HIV NAT with high-risk exposure [e]:

|

HIV NAT schedule for ongoing exposure through breast milk:

|

Q: Can ARV use affect the results of an infant’s HIV test?

A: Results of plasma HIV RNA nucleic acid tests (NATs) or plasma HIV RNA/DNA NATs can be affected by ARVs administered to newborns as prophylaxis or presumptive HIV therapy DHHS 2023; Patel, et al. 2020; Mazanderani, et al. 2018; Veldsman, et al. 2018; Uprety, et al. 2015. In New York State, a case of perinatal HIV transmission was identified through HIV NAT at 4 months of age following 3 prior negative NAT results (at birth, 2 weeks of age, and 4 weeks of age). The newborn was at high risk of perinatal HIV infection and received a 3-drug ARV regimen for presumptive HIV therapy, which was discontinued at 6 weeks of age. The infant was not exposed to HIV through breast milk, and there was no other postnatal HIV exposure risk. For this reason, the NYSDOH AI strongly advises adhering to the DHHS-recommended additional diagnostic HIV NAT, to be performed at 2 to 3 months of age after the time most 6-week multiagent ARV preventive regimens have been completed.

Q: Is additional HIV testing required for infants with ongoing exposure through breast milk from a parent who has HIV?

A: Yes. The DHHS recommends and the NYSDOH AI agrees that with ongoing exposure through breast milk from a parent with HIV, infants should be tested for HIV every 3 months for the duration of exposure. HIV testing is also recommended at 3 times after the last exposure to breast milk: 4 to 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months.

Coordination between the pediatric care provider and the maternal HIV care provider is critical. Maternal viral load monitoring is recommended every 1 to 2 months during breastfeeding. Additional infant virologic testing, including an immediate NAT, is indicated if maternal viral load becomes detectable during breastfeeding. For additional testing recommendations for infants exposed to breast milk in the setting of detectable maternal viral load, refer to DHHS > Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy and Interventions to Reduce Perinatal HIV Transmission in the United States.

Congenital Syphilis, cCMV, and PCP Prophylaxis

Congenital Syphilis

Q: Is congenital syphilis a concern for infants with perinatal HIV exposure?

A: Yes. Concomitant sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including syphilis, are common in individuals with HIV. Comprehensive STI screening to identify disease is critical because coinfection increases the risk of adverse perinatal and neonatal outcomes, including likely higher rates of in utero transmission. Infants born to individuals with HIV and concurrent STIs require prompt evaluation to exclude the possibility of transmission of additional infectious agents Adachi(a), et al. 2018.

No data exist to suggest that infants with congenital syphilis born to individuals with HIV and syphilis require evaluation, therapy, or follow-up for syphilis different than what is recommended for all infants with syphilis. The NYSDOH AI recommends that clinicians obtain serologic screening for syphilis for pregnant patients with HIV at the first prenatal visit, during the third trimester (28 to 32 weeks of gestation), and at delivery. See the NYSDOH AI guideline HIV Testing During Pregnancy, at Delivery, and Postpartum and the interim NYSDOH guidance regarding amendments to Public Health Law and prenatal syphilis screening.

Q: What are the recommendations for care in infants with congenital syphilis?

A: Treatment for congenital syphilis in infants is determined based on maternal history of syphilis infection and treatment, and current laboratory and physical examination results. All infants diagnosed with congenital syphilis should be physically and serologically monitored closely in the months following birth.

Clinicians should refer to the current Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of neonates with congenital syphilis that is confirmed or highly probable, possible, less likely, or unlikely. New York State clinicians may contact the Clinical Education Initiative Sexual Health Center of Excellence to access expert medical consultation on diagnosis, treatment, and management of STD infections at 866-637-2342.

Congenital Cytomegalovirus (cCMV)

Q: Is cCMV a concern for infants perinatally exposed to HIV?

A: Yes. HIV-exposed infants may be at higher risk for acquiring cCMV during pregnancy. Infants with HIV infection, particularly those who acquired HIV in utero, are at greatest risk for cCMV. Screening for cCMV is an important component of a comprehensive evaluation needed for HIV-exposed infants, particularly those born to individuals not on ART during pregnancy Adachi(b), et al. 2018.

Screening and early diagnosis of cCMV is the New York State standard of care to promote early intervention, monitoring, and medical care that optimizes hearing and developmental outcomes American Academy of Pediatrics 2018; Marsico and Kimberlin 2017; Rawlinson, et al. 2017.

For clinical recommendations, see DHHS > Initial Postnatal Management of the Neonate Exposed to HIV. cCMV is the most common intrauterine infection and the leading nongenetic cause of sensorineural hearing loss in children in the United States Grosse, et al. 2017. One in every 200 infants is born with cCMV infection, and approximately 20% of these infants will develop long-term health problems such as hearing or vision loss, intellectual disability, seizures, or developmental delay NYS Senate 2018.

| NEW YORK STATE LAW |

|

PCP Prophylaxis

Q: Is any prophylaxis against HIV-related opportunistic infections recommended for perinatally exposed infants?

A: Yes. Clinicians should initiate prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (previously P. carinii pneumonia; PCP) at 6 weeks of age for all HIV-exposed infants unless HIV diagnostic testing definitively or presumptively excludes HIV infection; if HIV diagnostic testing results are negative by 5 weeks of age, PCP prophylaxis is not necessary. See DHHS > Initial Postnatal Management of the Neonate Exposed to HIV.

Initial Postnatal Management

Q: What are the NYSDOH AI good practices for managing discharge and initial postnatal care of infants perinatally exposed to HIV?

A: NYSDOH AI good practices include:

- Continuing to educate parents or guardians about safe infant feeding options (including avoiding use of premasticated food), medical follow-up, antiretroviral medication (ARV) administration, and available support services

- Scheduling maternal and pediatric appointments prior to discharge

- Informing parents or guardians of the rationale for serial HIV testing, the testing schedule recommended for their infant, how to access HIV testing at the recommended times, and how results will be interpreted and communicated

- Ensuring that parents or guardians are aware of the symptoms of acute HIV infection and how and when to access care if any of those symptoms occur in their infant

- Providing ARV medications (not just prescriptions) to the parent or guardian who accompanies an infant upon hospital discharge. Ideally, any necessary tools, such as an oral syringe, should be provided as well.

- Ensuring that the parents or guardians know how and when to obtain and administer the infant’s ARV medications and potential adverse effects

Q: When should clinicians discuss infant feeding with a parent who has HIV?

A: The NYSDOH AI and the DHHS strongly encourage clinicians to engage pregnant patients with HIV in shared decision-making about infant feeding:

- As early as possible in pregnancy and throughout pregnancy

- After delivery

- Before hospital discharge

- At each postnatal visit. Assess the patient’s feeding practices, identify barriers, and provide supports for the appropriate implementation of the patient’s chosen method, including replacement feeding or formula feeding. See DHHS > Infant Feeding for Individuals With HIV in the United States.

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

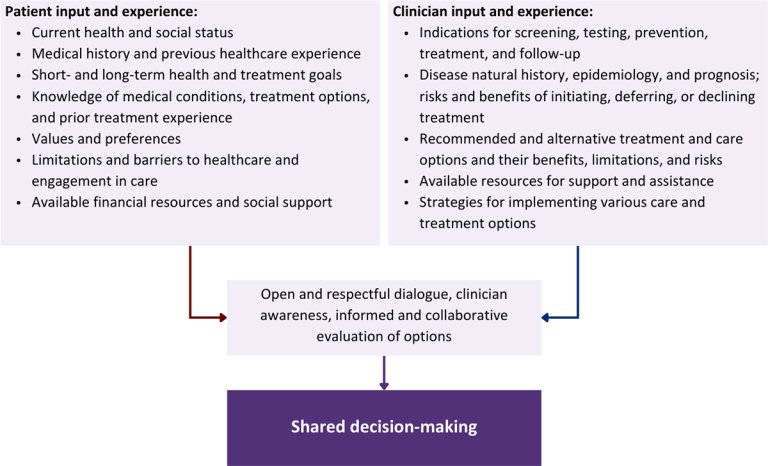

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Adachi(a) K., Xu J., Yeganeh N., et al. Combined evaluation of sexually transmitted infections in HIV-infected pregnant women and infant HIV transmission. PLoS One 2018;13(1):e0189851. [PMID: 29304083]

Adachi(b) K., Xu J., Ank B., et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus and HIV perinatal transmission. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2018;37(10):1016-21. [PMID: 30216294]

American Academy of Pediatrics. Summaries of infectious diseases: cytomegalovirus infection. Red book: report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases; 2018. https://doi.org/10.1542/9781610021470

DHHS. Recommendations for the use of antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV transmission in the United States. 2023 Jan 31. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/perinatal/antiretroviral-management-newborns-perinatal-hiv-exposure-or-hiv-infection [accessed 2023 Aug 31]

Fiscus S. A., Schoenbach V. J., Wilfert C. Short courses of zidovudine and perinatal transmission of HIV. N Engl J Med 1999;340(13):1040-43. [PMID: 10189281]

Grosse S. D., Dollard S. C., Kimberlin D. W. Screening for congenital cytomegalovirus after newborn hearing screening: what comes next?. Pediatrics 2017;139(2):e20163837. [PMID: 28119427]

Marsico C., Kimberlin D. W. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection: advances and challenges in diagnosis, prevention and treatment. Ital J Pediatr 2017;43(1):1-8. [PMID: 28416012]

Mazanderani A. H., Moyo F., Kufa T., et al. Brief report: declining baseline viremia and escalating discordant HIV-1 confirmatory results within South Africa's early infant diagnosis program, 2010-2016. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;77(2):212-16. [PMID: 29084045]

NYS Senate. Senate Bill S2816: requires urine polymerase chain reaction testing for cytomegalovirus of newborns with hearing impairments. 2018 Oct 2. https://www.nysenate.gov/legislation/bills/2017/s2816/amendment/original [accessed 2023 Aug 31]

NYSDOH. Unpublished data; 2022.

Patel F., Thurman C., Liberty A., et al. Negative diagnostic PCR tests in school-aged, HIV-infected children on antiretroviral therapy since early life in Johannesburg, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2020;83(4):381-89. [PMID: 31913997]

Rawlinson W. D., Boppana S. B., Fowler K. B., et al. Congenital cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy and the neonate: consensus recommendations for prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Lancet Infect Dis 2017;17(6):e177-88. [PMID: 28291720]

Uprety P., Chadwick E. G., Rainwater-Lovett K., et al. Cell-associated HIV-1 DNA and RNA decay dynamics during early combination antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected infants. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(12):1862-70. [PMID: 26270687]

Veldsman K. A., Maritz J., Isaacs S., et al. Rapid decline of HIV-1 DNA and RNA in infants starting very early antiretroviral therapy may pose a diagnostic challenge. AIDS 2018;32(5):629-34. [PMID: 29334551]

Wade N. A., Birkhead G. S., Warren B. L., et al. Abbreviated regimens of zidovudine prophylaxis and perinatal transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus. N Engl J Med 1998;339(20):1409-14. [PMID: 9811915]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines | |

| Date of original publication | October 11, 2023 |

| Intended users | NYS clinicians |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures. |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on May 8, 2024