Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: May 21, 2021

Lead author: Hector I. Ojeda-Martinez, MD

Writing group: Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 24, 2018

This guideline on hepatitis A virus (HAV) and HIV coinfection was developed by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI). The purpose of this guideline is to inform New York State clinicians about HAV/HIV coinfection, including screening, vaccination, and post-exposure prophylaxis, to accomplish the following:

- Increase the number of individuals in New York State with HIV who are screened and vaccinated against HAV.

- Provide evidence-based recommendations for post-exposure prophylaxis in adults with HIV who experience an HAV exposure.

- Integrate current evidence-based clinical recommendations into the healthcare-related implementation strategies of the Ending the Epidemic initiative, which seeks to end the AIDS epidemic in New York State.

The NYSDOH AI guideline Immunizations for Adults WIth HIV includes recommendations for HAV vaccination.

Note on “experienced” and “expert” HIV care providers: Throughout this guideline, when reference is made to “experienced HIV care provider” or “expert HIV care provider,” those terms are referring to the following 2017 NYSDOH AI definitions:

- Experienced HIV care provider: Practitioners who have been accorded HIV Experienced Provider status by the American Academy of HIV Medicine or have met the HIV Medicine Association’s definition of an experienced provider are eligible for designation as an HIV Experienced Provider in New York State. Nurse practitioners and licensed midwives who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV in collaboration with a physician may be considered HIV Experienced Providers as long as all other practice agreements are met (8 NYCRR 79-5:1; 10 NYCRR 85.36; 8 NYCRR 139-6900). Physician assistants who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV under the supervision of an HIV Specialist physician may also be considered HIV Experienced Providers (10 NYCRR 94.2)

- Expert HIV care provider: A provider with extensive experience in the management of complex patients with HIV.

Burden of HAV

The total annual reported cases of HAV in the United States decreased consistently between 2000 (13,397 cases) and 2014 (1,239 cases), with the decline attributed to the inclusion of HAV vaccination in the recommended pediatric immunization panels for children aged 2 to 18 years CDC 2018. Since 2014, however, the number of cases reported in the United States has increased, reaching 12,474 in 2018 CDC 2022. In 2017 and 2018, outbreaks among people who use drugs, homeless people, and men who have sex with men (MSM) contributed to substantial increases in the reported cases of HAV. A study using nationally representative data found that from 2007 to 2016, HAV susceptibility among nonvaccinated U.S.-born adults aged 20 years or older was approximately 74.1% Yin, et al. 2020.

In 2019, the NYSDOH issued an advisory on increases in HAV infection and noted the following:

- In New York State (excluding New York City) the annual number of reported HAV cases (2,019) represented a 235% increase between 2016 and 2018 NYSDOH 2019.

- People at high risk for HAV infection are those who use injection or noninjection drugs, have unstable housing or are homeless, are or were recently incarcerated, and who are MSM NYSDOH 2019.

- In New York City, the number of reported HAV cases increased 64% from 2018 to 2019, with the increase largely due to outbreaks among MSM NYCDOHMH 2020.

Transmission and Prevention

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Pre-Exposure Vaccination

Post-Exposure Immune Globulin

|

Abbreviations: CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HAV, hepatitis A virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G. Notes:

|

Transmission

The modes of HAV transmission are well established: ingestion of contaminated water and food, such as raw clams or oysters; oral-anal contact; person-to-person spread via fomites, such as shared utensils or bath towels; or, very rarely, blood or blood product transfusion. In the last few years, HAV outbreaks have largely been attributed to foodborne transmission and close person-to-person contact with an individual with HAV CDC 2022.

Men who have sex with men (MSM) and individuals who use drugs are at increased risk for HAV infection, and data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2007 to 2016 indicate that, among adults born in the United States aged ≥20 years, the prevalences of HAV susceptibility and nonvaccination, respectively, were 67.5% and 65.2% among MSM and 72.9% and 73.1% among individuals who reported injection drug use Yin, et al. 2020.

Pre-Exposure Vaccination

All adults with HIV should receive an HAV IgG test, and those who are antibody-negative should be vaccinated against HAV Nelson, et al. 2020.

Infection with HAV can be prevented by active immunization before exposure with either of the 2 currently licensed vaccines, which are considered equivalent in efficacy. HAV vaccines are highly immunogenic in immunocompetent adults, with >95% seroconversion. However, the seroconversion rates and the geometric mean serum antibodies in individuals with HIV are lower than in those without HIV, with response rates from 50% to 95% Kemper, et al. 2003; Wallace, et al. 2004; Rimland and Guest 2005; Shire, et al. 2006; Weissman, et al. 2006; Mena, et al. 2013. HAV vaccine appears to have no effect on the course of HIV infection or on plasma HIV viral load. A combined HAV and hepatitis B virus vaccine is also available and can be used in people susceptible to both hepatitis A and B. It is given in three total doses at 0, 1, and 6 months.

Administration of HAV vaccine is recommended for all adults with HIV regardless of CD4 count. An effective antibody response may not occur in up to 15% of immunocompromised patients Wallace, et al. 2004; Mena, et al. 2013. This committee recommends follow-up HAV antibody testing for patients who are at increased risk for HAV-related morbidity and mortality (see above) to verify vaccine efficacy and to identify those who should be counseled to avoid infection because of continued susceptibility.

Post-Exposure Immune Globulin

Immune serum globulin is the recommended HAV post-exposure prophylaxis for patients with HIV and should be given to individuals who are susceptible to HAV infection within 2 weeks after an exposure to an HAV-infected household contact, sexual partner, or needle-sharing partner ACIP 2007; CDC 2022. Consideration should also be given to patients with HIV who are providing other types of ongoing, close personal contact with someone with HAV (e.g., a regular babysitter or caretaker) ACIP 2007; CDC 2022. A single dose of 0.1 mL/kg intramuscularly is effective in preventing infection or attenuating HAV infection that might result from such an exposure Nelson 2017. Concurrent administration of HAV vaccine with immune serum globulin is indicated for individuals at risk for future infection (see above).

Management of HAV/HIV Coinfection

| RECOMMENDATION |

Management of HAV/HIV Coinfection

|

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; HAV, hepatitis A virus. |

Morbidity and mortality: The incubation period of HAV infection averages 28 days (range, 15 to 50 days). Although HAV does not cause chronic hepatitis, it is not a benign disease; the morbidity in adults is substantial. Young children tend to have asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic disease, whereas older children and adults have more severe illness, with jaundice occurring in approximately 70% of cases Cuthbert 2001. Approximately 40.8% of patients with reported cases of acute HAV required hospitalization in 2013 CDC 2015. Overall case fatality is low, ranging from 0.3% to 0.6% for all ages and up to 1.8% among adults aged >50 years CDC 2015.

| KEY POINT |

|

Coinfection: HAV does not cause more severe clinical illness in people with HIV than in people without. Patients with HIV may have significantly higher HAV viral load levels and significantly prolonged durations of HAV viremia than people who do not have HIV Gallego, et al. 2011, which may result in a prolonged duration of risk of HAV transmission to others.

Maintain ART: Patients with HIV and acute HAV infection rarely require even temporary interruption of ART. Cessation of ART should be avoided whenever possible because of the potential long-term consequences, such as reduced viral suppression when ART is reinstituted Lutwick 1999; El-Sadr, et al. 2008. In the rare instances when interruption of ART is indicated for management of fulminant liver disease, clinicians should consult with a care provider experienced in the treatment of hepatitis and HIV.

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS: PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT OF HEPATITIS A VIRUS INFECTION IN ADULTS WITH HIV |

Pre-Exposure Vaccination

Post-Exposure Immune Globulin

Management of HAV/HIV Coinfection

|

Abbreviations: ART, antiretroviral therapy; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; HAV, hepatitis A virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G. Notes:

|

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

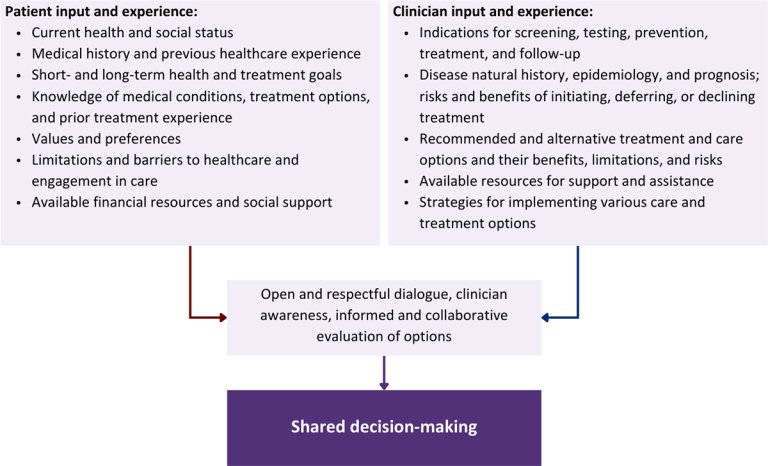

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

ACIP. Update: prevention of hepatitis A after exposure to hepatitis A virus and in international travelers. Updated recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2007;56(41):1080-84. [PMID: 17947967]

CDC. Surveillance for viral hepatitis – United States, 2013. 2015 May 31. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2013surveillance/index.htm [accessed 2021 Mar 19]

CDC. Surveillance for viral hepatitis – United States, 2016. 2018 Apr 16. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2016surveillance/index.htm [accessed 2021 Mar 19]

CDC. Hepatitis A outbreaks in the United States. 2022 Jan 19. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/outbreaks/hepatitisaoutbreaks.htm [accessed 2021 Mar 19]

Cuthbert J. A. Hepatitis A: old and new. Clin Microbiol Rev 2001;14(1):38-58. [PMID: 11148002]

El-Sadr W. M., Grund B., Neuhaus J., et al. Risk for opportunistic disease and death after reinitiating continuous antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV previously receiving episodic therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2008;149(5):289-99. [PMID: 18765698]

Gallego M., Robles M., Palacios R., et al. Impact of acute hepatitis A virus (HAV) infection on HIV viral load in HIV-infected patients and influence of HIV infection on acute HAV infection. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2011;10(1):40-42. [PMID: 21368013]

Kemper C. A., Haubrich R., Frank I., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of hepatitis A vaccine in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Infect Dis 2003;187(8):1327-31. [PMID: 12696015]

Lutwick L. I. Clinical interactions between human immunodeficiency virus and the human hepatitis viruses. Infect Dis Clin Pract 1999;8(1):9-20. https://journals.lww.com/infectdis/Fulltext/1999/01000/CLINICAL_INTERACTIONS_BETWEEN_HUMAN.3.aspx

Mena G., García-Basteiro A. L., Llupià A., et al. Factors associated with the immune response to hepatitis A vaccination in HIV-infected patients in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Vaccine 2013;31(36):3668-74. [PMID: 23777950]

Nelson N. P. Updated dosing instructions for immune globulin (human) GamaSTAN S/D for hepatitis A virus prophylaxis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(36):959-60. [PMID: 28910270]

Nelson N. P., Weng M. K., Hofmeister M. G., et al. Prevention of hepatitis A virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep 2020;69(5):1-38. [PMID: 32614811]

NYCDOHMH. Hepatitis A, B, and C in New York City: 2019 annual report. 2020 Dec. https://hepfree.nyc/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Viral-Hep-2019-Annual-Report_Final_Web.pdf [accessed 2021 Mar 24]

NYSDOH. Health advisory: outbreak of hepatitis A virus. 2019 Dec 12. https://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/communicable/hepatitis/hepatitis_a/docs/2019-12-12_health_advisory.pdf [accessed 2021 Mar 19]

Rimland D., Guest J. L. Response to hepatitis A vaccine in HIV patients in the HAART era. AIDS 2005;19(15):1702-4. [PMID: 16184045]

Shire N. J., Welge J. A., Sherman K. E. Efficacy of inactivated hepatitis A vaccine in HIV-infected patients: a hierarchical bayesian meta-analysis. Vaccine 2006;24(3):272-79. [PMID: 16139398]

Wallace M. R., Brandt C. J., Earhart K. C., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated hepatitis A vaccine among HIV-infected subjects. Clin Infect Dis 2004;39(8):1207-13. [PMID: 15486846]

Weissman S., Feucht C., Moore B. A. Response to hepatitis A vaccine in HIV-positive patients. J Viral Hepat 2006;13(2):81-86. [PMID: 16436125]

Yin S., Barker L., Ly K. N., et al. Susceptibility to hepatitis A virus infection in the United States, 2007-2016. Clin Infect Dis 2020;71(10):e571-79. [PMID: 32193542]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines | |

| Date of original publication | August 24, 2018 |

| Date of current publication | May 21, 2021 |

| Highlights of changes, additions, and updates in the May 21, 2021 edition |

|

| Intended users | New York State clinicians in outpatient settings who provide primary and HIV specialty care for adults who have or are at risk of acquiring hepatitis A virus infection |

| Lead author |

Hector I. Ojeda-Martinez, MD |

| Writing group |

Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

| Related NYSDOH AI guidelines | |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on January 18, 2024