Purpose of This Guidance

Reviewed and updated: Eugenia L. Siegler, MD; May 5, 2023

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Jessica Rodrigues; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: July 31, 2020

Purpose: Because published evidence to support clinical recommendations is not currently available, this guidance on addressing the needs of older patients in HIV care was developed by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) to present good practices to help clinicians recognize and address the needs of older patients with HIV.

The goals of this guidance are to:

- Raise clinicians’ awareness of the needs and concerns of patients with HIV who are ≥50 years old.

- Inform clinicians about an aging-related approach to older patients with HIV.

- Highlight good practices to help clinicians provide optimal care for this population.

- Provide resources about aging with HIV for healthcare providers and their patients.

- Suggest steps to guide medical settings in implementing geriatric care into HIV clinical practice.

Demographics: At the end of 2020, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, more than 52% of people with HIV in the United States were ≥50 years old CDC 2023. As of the end of 2020 in New York State, 60% of people with HIV were ≥50 years old, and nearly 30% were ≥60 years old NYCDHMH 2021. That same year, almost 19% of new HIV diagnoses in New York State occurred in people ≥50 years old, and one-third of them had progressed to AIDS at the time of diagnosis NYCDHMH 2021. In light of these New York State demographics, the NYSDOH AI has developed this guidance to help care providers expand services for older people with HIV.

Ensuring appropriate care delivery: Although the effects of HIV on aging have been studied for years, HIV care has been acknowledged only recently as a domain of geriatrics Guaraldi and Rockwood 2017. Geriatric assessment provides a complete view of a patient’s function, cognition, and health, and improves prognostication and treatment decisions Singh, et al. 2017. As the population with HIV grows older, the application of the principles of geriatrics can enhance the quality of care.

Definition of terms:

- “Older”: Published studies differ in their definitions of older patients with HIV (e.g., ≥50 years old, ≥55 years old, ≥60 years old), and the needs of individuals within different age groups may differ markedly. This guidance defines older patients as those ≥50 years old, which is the same definition used by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in Adults and Adolescents With HIV DHHS 2023. Nonetheless, clinical programs may wish to distinguish different strata within this population, as their needs may differ; a local needs assessment is key to determining how best to care for this population as its age distribution continues to change.

- “Long-term survivor”: The term long-term survivor has different meanings. Some have defined it as having been diagnosed with HIV before the era of effective antiretroviral therapy; others have defined it in terms of the length of time an individual has lived with HIV, e.g., for at least 1 or 2 decades. Long-term survivors can be any age. For example, older teens and adults who were perinatally infected are long-term survivors. It is useful to ask patients if they self-identify as long-term survivors and what that term means to them.

Effects of Aging

Long-term survivors appear to have physiologic changes consistent with advanced or accentuated aging Akusjarvi and Neogi 2023, even at the level of gene expression and modification Esteban-Cantos, et al. 2021; De Francesco, et al. 2019. When compared with age-matched controls who do not have HIV, older patients with HIV have more comorbidities Verheij, et al. 2023 and polypharmacy Kong, et al. 2019; Guaraldi, et al. 2018; poorer bone health Erlandson, et al. 2016; and higher rates of cognitive decline Goodkin, et al. 2017; Vance, et al. 2016, depression Do, et al. 2014, and aging-related syndromes, such as gait impairment and frailty Falutz 2020. Mental health can also be affected in many ways; in 1 study of individuals with HIV ≥50 years old in San Francisco, the majority of participants reported loneliness, poor social support, and/or depression, and nearly half reported anxiety John, et al. 2016. Older individuals may also experience negative effects due to the stigma of ageism, which may be compounded by other kinds of stigma, such as racial, gender, or HIV-related stigma Johnson Shen, et al. 2019. In addition, long-term survivors, who may have expected to die at a young age like so many of their peers, may feel survivor’s guilt Machado 2012.

These age-related concerns are not limited to long-term survivors. Although individuals who are ≥50 years old with newly diagnosed HIV are not likely to exhibit the same degree of age advancement as those who have lived a long time with HIV, they may have a delayed diagnosis, low CD4 cell counts, and AIDS at the time of diagnosis Tavoschi, et al. 2017. Late initiation of antiretroviral therapy increases the long-term risk of complications Molina, et al. 2018.

Sex differences in the effect of HIV on aging remain an area of controversy. Studies in several countries have found that women with HIV have life expectancies closer to their HIV-negative counterparts than do men with HIV, but this finding has not been supported by studies in North America Pellegrino, et al. 2023; Wandeler, et al. 2016; Samji, et al. 2013. A Canadian study showed shorter life expectancy among women with HIV than men with HIV Hogg, et al. 2017. Women with HIV in resource-rich countries appear to have a heightened risk of comorbidities Palella, et al. 2019, including cardiovascular disease Kovacs, et al. 2022; Stone, et al. 2017, cognitive loss Maki, et al. 2018, and more rapid declines in bone mineral density Erlandson, et al. 2018.

Approach to Aging in HIV Care

| GOOD PRACTICES |

|

Approach to Aging in HIV Care

|

Discuss aging-related concerns: It is essential to discuss aging-related concerns with patients with HIV who are ≥50 years old. Some HIV healthcare providers and their patients have enduring relationships. Such longstanding ties promote high levels of trust, but they can also inhibit exploration of new concerns and promote too tight a focus on keeping viral load undetectable and treating common comorbidities. As a consequence, older individuals with HIV may not recognize concerns as aging-related or may feel it is unnecessary or inappropriate to discuss aging.

Care of older patients with HIV begins with recognizing that aging-related issues are a fundamental part of primary care. Geriatric concerns do not supplant other medical conditions; they reframe them in light of a multiplicity of problems and a finite lifespan. A geriatric approach, even for people in their 50s, can improve the quality of care. Older people with HIV may range from 50 to 80 years old and beyond and are a heterogeneous group. Providing care for older patients requires balance to avoid ageism and neglect of essential care while at the same prevent excessive, dangerous, or unnecessary treatments. Determining what is appropriate for patients begins with an assessment of their health and their priorities.

Asking questions such as, “Have you thought about aging?” or “What would you like to know about aging with HIV?” creates opportunities to learn about patient’s concerns about the future and to discuss survivorship, guilt, ageism, financial worries, and other issues Del Carmen, et al. 2019. This is an opportunity to discuss healthy aging through lifestyle modifications that include exercise, diet, and socialization.

Sexual health: Older age does not preclude discussions of topics that are essential to health. For example, sexuality should be considered an essential part of health at any age. There is no age limit at which clinicians should stop taking a sexual history or discussing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for partners. Initiating discussions of sexual health, including topics such as erectile dysfunction and loss of libido in men, menopause and postmenopausal sex in women, and screening for sexually transmitted infections as needed, may also provide insights into relationships and the strength of a patient’s social network. For more information, see the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021 > Screening Recommendations.

Cancer screening: Overall, patient health and priorities, rather than age, direct the frequency of cancer screening in individuals with HIV. The literature on adherence to cancer screening guidelines among individuals with HIV is mixed, with most Corrigan, et al. 2019 but not all Barnes, et al. 2018 studies failing to find that older individuals were screened less frequently. In patients with a good prognosis, clinicians should continue to follow screening guidelines (see the NYSDOH AI guideline Comprehensive Primary Care for Adults With HIV > Routine Screening and Primary Prevention). Screening can be re-evaluated when it conflicts with a patient’s priorities or when a patient’s prognosis is poor.

Aging-related syndromes and comorbidities: Some health concerns take on greater relevance as individuals with HIV age. Geriatric or aging-related syndromes, such as frailty, have received special attention. Frailty, which can be measured as a physical construct or as an “accumulation of deficits,” is a measure of vulnerability Kehler, et al. 2022. Frailty has been associated with increases in falls Erlandson, et al. 2019 and mortality Piggott, et al. 2020; Kelly, et al. 2019, and multiple comorbidities Masters, et al. 2021; Kelly, et al. 2019 have been linked to its development. However, it is possible to reverse frailty. Early identification may enable increased resources for those at highest risk and may also draw attention to associated comorbidities. Cardiovascular risk is increased in people with HIV, as is osteoporosis. Guidelines for bone mineral density testing, in particular, are often not followed Birabaharan, et al. 2021, despite the higher rates of osteoporosis and fractures in people with HIV compared with age-matched controls Starup-Linde, et al. 2020.

Insurance and long-term care needs: Addressing aging-related concerns directly can help older patients with HIV discuss financial worries and prepare for the future when more personal assistance may be needed. Discussing insurance coverage with patients with HIV when they are in their 60s provides an opportunity to help them prepare for the transition from commercial insurance or SNPs to Medicare-based plans. Planning is essential because commercial insurance plans or SNPs often offer more comprehensive care coordination, medication coverage, and health-maintenance services than Medicare-based plans. People with HIV may need long-term care at an earlier age than those without HIV Justice and Akgun 2019. Open discussion about support systems can help patients begin to plan for their long-term care needs.

The 5Ms-an effective communication tool: The geriatric approach can be described as attention to the 5Ms: mind, mobility, multimorbidity, medications, and matters most Tinetti, et al. 2017. The 5Ms are a useful way to communicate geriatric principles or choose an area for screening. However, some aging-related syndromes (e.g., dizziness, incontinence) or activities of daily living may not easily fit into one of these categories. Nor do the 5Ms offer a structure for a comprehensive geriatric assessment. The following discussion addresses how the 5Ms can be used to understand and explain geriatric priorities and broaden the focus beyond specific comorbidities. The 5Ms are best viewed as an explanatory framework; it is important that screening and assessment be performed with formally recognized instruments (see Table 1: Assessment Domains for Older People With HIV and Selected Tools and Resources).

1. Mind: This category includes all domains of behavioral health, including cognition, mood, and other disorders. General assessment questions about instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., using transportation, managing medications, and handling finances) can provide information about practical concerns and offer clues about cognitive or emotional barriers to self-care. Healthcare providers can also use specific tools (i.e., Table 1) to screen patients for disorders such as depression or cognitive impairment, which may be caused by factors both related to and independent of HIV Winston and Spudich 2020. Even as the prevalence of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder has decreased among individuals with HIV, having multiple comorbidities can increase the risk of cognitive impairment Heaton, et al. 2023. Identifying factors that can be addressed to prevent or slow cognitive deterioration is a fundamental part of assessment in this category.

2. Mobility: Healthcare providers can begin to address mobility with a general assessment of activities of daily living to determine whether patients have difficulty dressing or bathing. Discussion of a patient’s fall risk can begin with a question such as, “Have you fallen in the past year?” or healthcare providers can use a comprehensive fall-risk screening tool.

3. Multimorbidity and multicomplexity: Care for older patients with HIV usually involves the management of multiple comorbidities, each of which may require treatment with multiple medications. Nonpharmacologic management (e.g., smoking cessation, dietary modification, exercise) can also improve symptoms associated with multiple comorbidities Fitch 2019.

A geriatric perspective recognizes that, in patients with multimorbidity, strict adherence to multiple disease-based treatment guidelines may not be possible or may jeopardize a patient’s health. Simultaneous management of multiple chronic conditions necessitates establishing treatment priorities Yarnall, et al. 2017, which requires understanding a patient’s priorities Tinetti, et al. 2019.

4. Medications: While older individuals with HIV are taking antiretroviral medications to suppress the virus, they may also be taking other medications to treat comorbidities, which can make medication management especially challenging. Polypharmacy is common, and women appear to be at higher risk than men, likely because of a higher prevalence of comorbidities Livio, et al. 2021. Medication evaluation should include a review of all medications, potential drug-drug interactions Livio and Marzolini 2019, and short- and long-term toxic effects. It may be beneficial to simplify antiretroviral and other medication regimens to ensure that harms from drug-drug interactions and other adverse effects of treatment are avoided Del Carmen, et al. 2019. Caution is required when adjusting or simplifying antiretroviral regimens if changes involve either initiating or discontinuing a medication with pharmacologic inhibitive or induction actions; these changes may affect levels of coadministered medications.

Consultation with a pharmacist can reduce drug-drug interactions and polypharmacy and help clinicians navigate the complexities of medication management in older patients Ahmed, et al. 2023. The University of Liverpool HIV Drug Interactions Checker is a useful tool for checking drug-drug interactions; also see NYSDOH AI Resource: ART Drug-Drug Interactions.

5. Matters most: This is the broadest category and includes medical and social priorities, sexual health, and advance directives. This category may also include discussion of palliative care and frank discussion of long-term care needs and end-of-life plans. Advance directives should be addressed and, if an advance directive is in place, revisited. It is preferable for the patient to designate a specific agent or agents who can speak for them when they are incapacitated. Patients who cannot or will not identify a trusted individual to be their agent can complete the NYSDOH Medical Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (MOLST) to describe their wishes regarding medical treatment. The MOLST can now also be documented electronically in the eMOLST registry.

Geriatric Screening and Assessment

General Screening Tools

Screening identifies individuals who are at risk for medical problems. Although care providers may order screening tests for specific diseases such as cancer, they may not be as familiar with screening tools designed to identify functional impairment or geriatric syndromes. In all cases, the same principles apply: brief, sensitive geriatric screening instruments such as those included in Box 1, below, can be used to identify patients who may need more intensive evaluation.

For those programs that are just starting to identify the needs of their older patients, a general screening questionnaire is an excellent place to start. General screening questionnaires are usually appropriate for all older patients and long-term survivors and often are performed annually around a patient’s birthday. Such screenings can be completed before a clinic visit; some questionnaires are completed by the patient and others are administered by a staff member. The modified World Health Organization integrated care for older people (ICOPE) screening tool has been tested for people with HIV in a New York State-wide pilot and can be administered by staff in person or over the phone; sites can also use other surveys based on workflows.

Why perform general geriatric screening? Not every patient requires a formal geriatric assessment. Tools for general geriatric screening are simple and cover a wide variety of domains; if the results indicate that more extensive assessment is warranted, then a more formal and comprehensive evaluation can be performed. Use of general screening tools can improve case-finding and, when coupled with referral, can enable targeted interventions but has not yet been shown to reduce hospitalizations or improve function Rubenstein, et al. 2007.

| Box 1: General Geriatric Screening Tools for Older Adults With HIV |

|

Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment

When a patient has a positive result on a general geriatric screening test, the clinician may consider a more comprehensive assessment using validated tools. Formal assessment is more effective than clinical judgment at uncovering problems Elam, et al. 1991; Pinholt, et al. 1987.

The Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment: The gold standard for geriatric evaluation is the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA), which assesses multiple domains of health and function Singh, et al. 2017. Because it is comprehensive, the CGA is lengthy, and its use may not be feasible in many clinical settings. In the general geriatric outpatient setting, the CGA has not been shown to reduce mortality or nursing home placement, although it may reduce hospital admissions Briggs, et al. 2022. The CGA is a complicated process, requiring both expert assessors and clear care plans to manage areas of deficit, and its mixed success in the community likely stems at least in part from the complexity of creating a system that effectively responds to the assessment and includes patient buy-in.

Consulting experts in geriatric care: Some academic centers have tested models of collaboration with geriatricians Davis, et al. 2022, including referral to geriatric consultants outside the practice, multidisciplinary geriatric care within the practice, and dual training of clinicians in geriatrics and HIV medicine. More models are being studied.

Choosing domains for focused assessment: Given the limitations in both the HIV care and geriatrics workforces Armstrong 2021; American Geriatrics Society 2017, access to geriatricians may not be feasible. Community-based programs wishing to assess specific domains in the absence of available expert clinicians may choose from among many options.

Recommendations from community advisory boards and patient surveys can advise sites about patient priorities, and results from general screenings can prompt more broad assessments to identify high-prevalence problems. It may be difficult to implement needed aging-related assessments when access to expertise or funding is limited, but every attempt should be made to assess aging-related issues to the degree possible. Table 1, below, lists domains of geriatric assessment and selected resources for older patients with HIV.

| Abbreviations: ACSM, American College of Sports Medicine; AGS, American Geriatrics Society; ART, antiretroviral therapy; ARV, antiretroviral medication; CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; CGA, Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment; GOALS, Give Offer Ask Listen Suggest; HIVMA, HIV Medicine Association; HRQOL, Health-Related Quality of Life; IDSA, Infectious Diseases Society of America; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NIH, National Institutes of Health; NYSDOH AI, New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute; SAMHSA, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; UCSF, University of California San Francisco; VACS, Veterans Aging Cohort Study. | |

| Table 1: Assessment Domains for Older People With HIV and Selected Tools and Resources | |

| Area for Assessment | Tools and Resources |

| Functional Deficits and Geriatric Syndromes | |

| Basic activities of daily living (general) | Katz Index of Independence in Activities of Daily Living: bathing, dressing, toileting, grooming, transferring, locomotion |

| Instrumental activities of daily living | The Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) Scale: telephone, transportation, housekeeping, medication management, financial management, meal preparation |

| Continence |

|

| Exercise prescription | |

| Frailty | CGA Toolkit Plus: Frailty |

| Mental Health | |

| Cognition |

|

| Social isolation, loneliness | Multiple screening tools and interventions are available through: |

| Other areas (e.g., depression, anxiety, stigma) | |

| Comorbidities and Medications | |

| Managing multiple chronic conditions | Decision making for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: executive summary for the American Geriatrics Society Guiding Principles on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity Boyd, et al. 2019 |

| Primary care of specific comorbidities | NYSDOH AI guideline Comprehensive Primary Care for Adults With HIV |

| ART choices and drug-drug interactions | |

| Medication choices and polypharmacy | |

| Bone health | Management algorithms:

|

| Nutrition (food insecurity, obesity, undernutrition) | |

| Quality of Life | |

| Advance directives | NYSDOH: |

| Caregiving (requiring and providing) | Next Step in Care Toolkits, Guides, and More for Health Care Providers |

| Elder mistreatment | |

| Overall health, pain management | |

| Palliative care, prognosis, and end-of-life plans | |

| Sexual health and menopause | |

Integrating the Needs of Older Patients Into Medical Care

This guidance is designed to foster a shift in the practitioner’s perspective when caring for older patients with HIV. However, the clinician cannot provide optimal care in the absence of support. Clinical practices can also begin to address HIV-related aging issues by taking the steps outlined in Box 2, below.

| Box 2: Six Steps to Integrating Needs of Older Patients Into HIV Medical Care |

| 1. Assess the clinic’s ability to meet the needs of older patients with HIV: |

|

| 2. Engage older patients with HIV in program planning: |

|

| 3. Consider options and develop protocols for identifying patients in need of aging-related care and services. For example, patients may be identified based on: |

|

| 4. Develop an assessment strategy: |

|

| 5. Develop protocols for referral: |

|

| 6. Link to the Aging Network for services: |

|

Download Box 2: Six Steps to Integrating Needs of Older Patients Into HIV Medical Care Printable PDF

| ONLINE RESOURCES FOR AGING AND GERIATRIC CARE |

Clinical Resources:

Services and Entitlements:

|

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

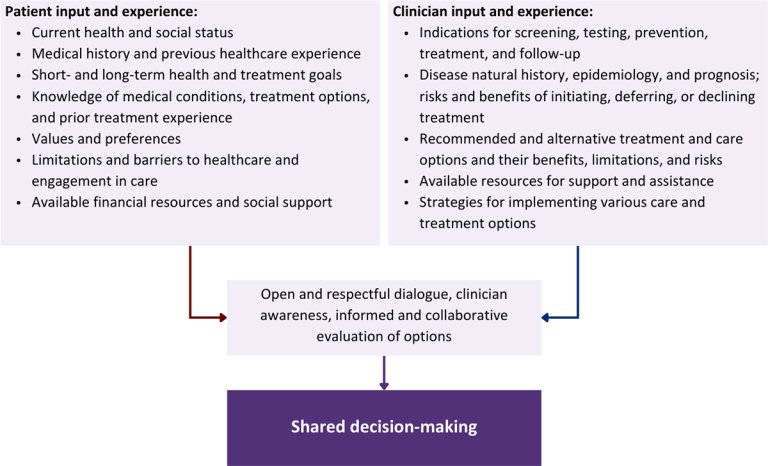

Rationale

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Ahmed A., Tanveer M., Dujaili J. A., et al. Pharmacist-involved antiretroviral stewardship programs in people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2023;37(1):31-52. [PMID: 36626156]

Akusjarvi S. S., Neogi U. Biological aging in people living with HIV on successful antiretroviral therapy: do they age faster?. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2023;20(2):42-50. [PMID: 36695947]

American Geriatrics Society. Projected future need for geriatricians. 2017 Feb. https://www.americangeriatrics.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Projected-Future-Need-for-Geriatricians_1.pdf [accessed 2023 Mar 27]

American Geriatrics Society. American Geriatrics Society 2019 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(4):674-94. [PMID: 30693946]

Armstrong W. S. The human immunodeficiency virus workforce in crisis: an urgent need to build the foundation required to end the epidemic. Clin Infect Dis 2021;72(9):1627-30. [PMID: 32211784]

Barnes A., Betts A. C., Borton E. K., et al. Cervical cancer screening among HIV-infected women in an urban, United States safety-net healthcare system. AIDS 2018;32(13):1861-70. [PMID: 29762164]

Birabaharan M., Kaelber D. C., Karris M. Y. Bone mineral density screening among people with HIV: a population-based analysis in the United States. Open Forum Infect Dis 2021;8(3):ofab081. [PMID: 33796595]

Biver E., Calmy A., Aubry-Rozier B., et al. Diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of bone fragility in people living with HIV: a position statement from the Swiss Association Against Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 2019;30(5):1125-35. [PMID: 30603840]

Boyd C., Smith C. D., Masoudi F. A., et al. Decision making for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: executive summary for the American Geriatrics Society Guiding Principles on the Care of Older Adults With Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(4):665-73. [PMID: 30663782]

Briggs R., McDonough A., Ellis G., et al. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment for community-dwelling, high-risk, frail, older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2022;5(5):CD012705. [PMID: 35521829]

Brown T. T., Hoy J., Borderi M., et al. Recommendations for evaluation and management of bone disease in HIV. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60(8):1242-51. [PMID: 25609682]

Bruce R. D., Merlin J., Lum P. J., et al. 2017 HIVMA of IDSA clinical practice guideline for the management of chronic pain in patients living with HIV. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65(10):e1-37. [PMID: 29020263]

CDC. HIV surveillance reports. 2023 Mar 9. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html [accessed 2023 Mar 27]

CMS. Medicare wellness visits. 2022 Aug. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/preventive-services/medicare-wellness-visits.html [accessed 2023 Mar 27]

Corrigan K. L., Wall K. C., Bartlett J. A., et al. Cancer disparities in people with HIV: a systematic review of screening for non-AIDS-defining malignancies. Cancer 2019;125(6):843-53. [PMID: 30645766]

Davis A. J., Greene M., Siegler E., et al. Strengths and challenges of various models of geriatric consultation for older adults living with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 2022;74(6):1101-6. [PMID: 34358303]

De Francesco D., Wit F. W., Bürkle A., et al. Do people living with HIV experience greater age advancement than their HIV-negative counterparts?. AIDS 2019;33(2):259-68. [PMID: 30325781]

Del Carmen T., Johnston C., Burchett C., et al. Special topics in the care of older people with HIV. Curr Treat Options Infect Dis 2019;11(4):388-400. [PMID: 33343235]

DHHS. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in adults and adolescents with HIV. 2023 Mar 23. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-arv/whats-new-guidelines [accessed 2023 Mar 27]

Do A. N., Rosenberg E. S., Sullivan P. S., et al. Excess burden of depression among HIV-infected persons receiving medical care in the United States: data from the Medical Monitoring Project and the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. PLoS One 2014;9(3):e92842. [PMID: 24663122]

Elam J. T., Graney M. J., Beaver T., et al. Comparison of subjective ratings of function with observed functional ability of frail older persons. Am J Public Health 1991;81(9):1127-30. [PMID: 1951822]

Erlandson K. M., Guaraldi G., Falutz J. More than osteoporosis: age-specific issues in bone health. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016;11(3):343-50. [PMID: 26882460]

Erlandson K. M., Lake J. E., Sim M., et al. Bone mineral density declines twice as quickly among HIV-infected women compared with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;77(3):288-94. [PMID: 29140875]

Erlandson K. M., Perez J., Abdo M., et al. Frailty, neurocognitive impairment, or both in predicting poor health outcomes among adults living with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 2019;68(1):131-38. [PMID: 29788039]

Esteban-Cantos A., Rodriguez-Centeno J., Barruz P., et al. Epigenetic age acceleration changes 2 years after antiretroviral therapy initiation in adults with HIV: a substudy of the NEAT001/ANRS143 randomised trial. Lancet HIV 2021;8(4):e197-205. [PMID: 33794182]

Falutz J. Frailty in people living with HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2020;17(3):226-36. [PMID: 32394155]

Fitch K. V. Contemporary lifestyle modification interventions to improve metabolic comorbidities in HIV. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2019;16(6):482-91. [PMID: 31776973]

Goodkin K., Miller E. N., Cox C., et al. Effect of ageing on neurocognitive function by stage of HIV infection: evidence from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study. Lancet HIV 2017;4(9):e411-22. [PMID: 28716545]

Greene M., Covinsky K. E., Valcour V., et al. Geriatric syndromes in older HIV-infected adults. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2015;69(2):161-67. [PMID: 26009828]

Guaraldi G., Malagoli A., Calcagno A., et al. The increasing burden and complexity of multi-morbidity and polypharmacy in geriatric HIV patients: a cross sectional study of people aged 65 - 74 years and more than 75 years. BMC Geriatr 2018;18(1):99. [PMID: 29678160]

Guaraldi G., Rockwood K. Geriatric-HIV medicine is born. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65(3):507-9. [PMID: 28387817]

Harding R. Palliative care as an essential component of the HIV care continuum. Lancet HIV 2018;5(9):e524-30. [PMID: 30025682]

Heaton R. K., Ellis R. J., Tang B., et al. Twelve-year neurocognitive decline in HIV is associated with comorbidities, not age: a CHARTER study. Brain 2023;146(3):1121-31. [PMID: 36477867]

Hogg R. S., Eyawo O., Collins A. B., et al. Health-adjusted life expectancy in HIV-positive and HIV-negative men and women in British Columbia, Canada: a population-based observational cohort study. Lancet HIV 2017;4(6):e270-76. [PMID: 28262574]

Hu J. S., Pierre E. F. Urinary incontinence in women: evaluation and management. Am Fam Physician 2019;100(6):339-48. [PMID: 31524367]

John M. D., Greene M., Hessol N. A., et al. Geriatric assessments and association with VACS Index among HIV-infected older adults in San Francisco. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2016;72(5):534-41. [PMID: 27028497]

Johnson Shen M., Freeman R., Karpiak S., et al. The intersectionality of stigmas among key populations of older adults affected by HIV: a thematic analysis. Clin Gerontol 2019;42(2):137-49. [PMID: 29617194]

Justice A. C., Akgun K. M. What does aging with HIV mean for nursing homes?. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67(7):1327-29. [PMID: 31063666]

Kehler D. S., Milic J., Guaraldi G., et al. Frailty in older people living with HIV: current status and clinical management. BMC Geriatr 2022;22(1):919. [PMID: 36447144]

Kelly S. G., Wu K., Tassiopoulos K., et al. Frailty is an independent risk factor for mortality, cardiovascular disease, bone disease, and diabetes among aging adults with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 2019;69(8):1370-76. [PMID: 30590451]

Koethe J. R., Lagathu C., Lake J. E., et al. HIV and antiretroviral therapy-related fat alterations. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2020;6(1):48. [PMID: 32555389]

Kong A. M., Pozen A., Anastos K., et al. Non-HIV comorbid conditions and polypharmacy among people living with HIV age 65 or older compared with HIV-negative individuals age 65 or older in the United States: a retrospective claims-based analysis. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2019;33(3):93-103. [PMID: 30844304]

Kovacs L., Kress T. C., Belin de Chantemele E. J. HIV, combination antiretroviral therapy, and vascular diseases in men and women. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2022;7(4):410-21. [PMID: 35540101]

Livio F., Deutschmann E., Moffa G., et al. Analysis of inappropriate prescribing in elderly patients of the Swiss HIV Cohort Study reveals gender inequity. J Antimicrob Chemother 2021;76(3):758-64. [PMID: 33279997]

Livio F., Marzolini C. Prescribing issues in older adults living with HIV: thinking beyond drug-drug interactions with antiretroviral drugs. Ther Adv Drug Saf 2019;10:2042098619880122. [PMID: 31620274]

Looby S. E. Clinical considerations for menopause and associated symptoms in women with HIV. Menopause 2023;30(3):329-31. [PMID: 36811963]

Machado S. Existential dimensions of surviving HIV: the experience of gay long-term survivors. J Hum Psychol 2012;52(1):6-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167810389049

Maki P. M., Rubin L. H., Springer G., et al. Differences in cognitive function between women and men with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2018;79(1):101-7. [PMID: 29847476]

Masters M. C., Perez J., Wu K., et al. Baseline neurocognitive impairment (NCI) is associated with incident frailty but baseline frailty does not predict incident NCI in older persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Clin Infect Dis 2021;73(4):680-88. [PMID: 34398957]

Molina J. M., Grund B., Gordin F., et al. Which HIV-infected adults with high CD4 T-cell counts benefit most from immediate initiation of antiretroviral therapy? A post-hoc subgroup analysis of the START trial. Lancet HIV 2018;5(4):e172-80. [PMID: 29352723]

Montoya J. L., Jankowski C. M., O'Brien K. K., et al. Evidence-informed practical recommendations for increasing physical activity among persons living with HIV. AIDS 2019;33(6):931-39. [PMID: 30946147]

National Health Policy Forum. Older Americans Act of 1965: programs and funding. 2012 Feb 23. https://hsrc.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1252&context=sphhs_centers_nhpf [accessed 2023 Mar 27]

NYCDHMH. HIV surveillance annual report, 2020. 2021 Dec. https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/hiv-surveillance-annualreport-2020.pdf [accessed 2023 Mar 27]

O'Mahony D., O'Sullivan D., Byrne S., et al. STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Age Ageing 2015;44(2):213-18. [PMID: 25324330]

Palella F. J., Hart R., Armon C., et al. Non-AIDS comorbidity burden differs by sex, race, and insurance type in aging adults in HIV care. AIDS 2019;33(15):2327-35. [PMID: 31764098]

Pellegrino R. A., Rebeiro P. F., Turner M., et al. Sex and race disparities in mortality and years of potential life lost among people with HIV: a 21-year observational cohort study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023;10(1):ofac678. [PMID: 36726547]

Piggott D. A., Bandeen-Roche K., Mehta S. H., et al. Frailty transitions, inflammation, and mortality among persons aging with HIV infection and injection drug use. AIDS 2020;34(8):1217-25. [PMID: 32287069]

Pinholt E. M., Kroenke K., Hanley J. F., et al. Functional assessment of the elderly. A comparison of standard instruments with clinical judgment. Arch Intern Med 1987;147(3):484-88. [PMID: 3827424]

Rubenstein L. Z., Alessi C. A., Josephson K. R., et al. A randomized trial of a screening, case finding, and referral system for older veterans in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55(2):166-74. [PMID: 17302651]

Saliba D., Elliott M., Rubenstein L. Z., et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: a tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49(12):1691-99. [PMID: 11844005]

Samji H., Cescon A., Hogg R. S., et al. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One 2013;8(12):e81355. [PMID: 24367482]

Savoy M., O'Gurek D., Brown-James A. Sexual health history: techniques and tips. Am Fam Physician 2020;101(5):286-93. [PMID: 32109033]

Singh H. K., Del Carmen T., Freeman R., et al. From one syndrome to many: incorporating geriatric consultation into HIV care. Clin Infect Dis 2017;65(3):501-6. [PMID: 28387803]

Starup-Linde J., Rosendahl S. B., Storgaard M., et al. Management of osteoporosis in patients living with HIV-a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2020;83(1):1-8. [PMID: 31809356]

Stone L., Looby S. E., Zanni M. V. Cardiovascular disease risk among women living with HIV in North America and Europe. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2017;12(6):585-93. [PMID: 28832367]

Tavoschi L., Gomes Dias J., Pharris A. New HIV diagnoses among adults aged 50 years or older in 31 European countries, 2004-15: an analysis of surveillance data. Lancet HIV 2017;4(11):e514-21. [PMID: 28967582]

Tinetti M., Huang A., Molnar F. The geriatrics 5M's: A new way of communicating what we do. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65(9):2115. [PMID: 28586122]

Tinetti M., Naik A. D., Dindo L., et al. Association of patient priorities-aligned decision-making with patient outcomes and ambulatory health care burden among older adults with multiple chronic conditions: a nonrandomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179(12):1688-97. [PMID: 31589281]

Vance D. E., Rubin L. H., Valcour V., et al. Aging and neurocognitive functioning in HIV-infected women: a review of the literature involving the Women's Interagency HIV Study. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2016;13(6):399-411. [PMID: 27730446]

Verheij E., Boyd A., Wit F. W., et al. Long-term evolution of comorbidities and their disease burden in individuals with and without HIV as they age: analysis of the prospective AGE(h)IV cohort study. Lancet HIV 2023;10(3):e164-74. [PMID: 36774943]

Wandeler G., Johnson L. F., Egger M. Trends in life expectancy of HIV-positive adults on antiretroviral therapy across the globe: comparisons with general population. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016;11(5):492-500. [PMID: 27254748]

Winston A., Spudich S. Cognitive disorders in people living with HIV. Lancet HIV 2020;7(7):e504-13. [PMID: 32621876]

Yarnall A. J., Sayer A. A., Clegg A., et al. New horizons in multimorbidity in older adults. Age Ageing 2017;46(6):882-88. [PMID: 28985248]

Yourman L. C., Lee S. J., Schonberg M. A., et al. Prognostic indices for older adults: a systematic review. JAMA 2012;307(2):182-92. [PMID: 22235089]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines | |

| Date of original publication | July 31, 2020 |

| Date of current publication | May 05, 2023 |

| Highlights of changes, additions, and updates in the May 05, 2023 edition |

— |

| Intended users | NYS clinicians |

| Lead author |

Eugenia L. Siegler, MD |

| Writing group |

Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Joseph P. McGowan, MD, FACP, FIDSA; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Jessica Rodrigues, ; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

| Related NYSDOH AI guidelines |

Related NYSDOH AI Guidance |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on October 20, 2023