Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: October 6, 2022

Lead author: Christine A. Kerr, MD

Writing group: Joshua S. Aron, MD; David E. Bernstein, MD; Colleen Flanigan, RN, MS; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Guideline Committee

Date of original publication: October 6, 2022

This guideline on pretreatment assessment of patients with chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) was developed by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) to guide primary care providers and other practitioners in New York State in all aspects of treating and curing patients with chronic HCV. The guideline aims to achieve the following goals:

- Provide evidence-based treatment guidelines to New York State clinicians to increase the number of New York State residents with chronic HCV who are treated and cured.

- Provide guidance to clinicians on key pretreatment assessment criteria to ensure that HCV medications are prescribed safely and correctly and that all patients receive the highest quality of care.

- Provide evidence-based clinical recommendations to support the goals of the New York State Hepatitis C Elimination Plan (NY Cures HepC).

Medical History and Physical Examination

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Medical History and Physical Examination

|

Abbreviations: CrCl, creatinine clearance; DAA, direct-acting antiviral; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus. |

With few exceptions, nonpregnant patients with confirmed HCV are candidates for treatment EASL 2020; Ghany and Morgan 2020. Treatment of HCV infection reduces all-cause mortality, regardless of disease stage Simmons, et al. 2015. Patients who are not candidates for treatment with DAAs are those with a life expectancy of fewer than 12 months or for whom treatment or liver transplantation would not improve symptoms or prognosis AASLD/IDSA 2021. For recommendations for pregnant patients with chronic HCV and those who become pregnant while taking antiviral therapy for chronic HCV, see the NYSDOH AI guideline Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Adults > HCV Testing and Management in Pregnant Adults.

Screening for mental health and substance use disorders and providing treatment or referral as needed is essential but is not a reason to defer treatment. The approach to treating HCV infection in patients with mental health or substance use disorders is the same as for other patients with HCV. Patients with active substance use or mental health disorders can and should be successfully treated, although additional support for adherence, follow-up, and harm reduction may be necessary Granozzi, et al. 2021; Hajarizadeh, et al. 2020; Torrens, et al. 2020; Gountas, et al. 2018; Sackey, et al. 2018; Tsui, et al. 2016.

Key elements of medical history and physical examination: Table 1, below, lists components of the patient history and physical examination that apply specifically to pretreatment assessment of patients with chronic HCV.

| Table 1: Key Elements of Patient History and Physical Examination |

|

| Abbreviations: anti-HBc, hepatitis B core antibody; anti-HBs, hepatitis B surface antibody; ART, antiretroviral therapy; DAA, direct-acting antiviral; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G.

Notes:

|

|

| Elements of Patient History | Rationale |

| Previous treatment for HCV infection | Previous regimen and treatment outcome will guide choice and duration of therapy. |

| History of hepatic decompensation | Warrants referral to a liver disease specialist. |

| History of renal disease | Findings may influence choice of regimen. |

| Medication history and current medications, including over-the-counter and herbal products | Carefully consider potential drug-drug interactions with DAAs. See American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD)/Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) or University of Liverpool HEP Drug Interactions. |

| Pregnancy status and plans |

|

| HIV infection |

|

| History of infection/vaccination status |

|

| Elements of Pretreatment Physical Examination |

Clinical Details |

| Presence or absence of ankle edema, abdominal veins, jaundice, palmar erythema, gynecomastia, spider telangiectasia, ascites, encephalopathy, and asterixis | Presence may suggest cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis and may require additional evaluation and management or treatment. |

| Presence or absence of physical signs related to extrahepatic manifestations of HCV, such as porphyria cutanea tarda, vasculitis, or lichen planus | Presence may increase urgency of HCV treatment and may require additional evaluation and treatment needs [e]. |

| Liver size by palpation or auscultation for hepatomegaly or splenomegaly, as well as tenderness or hepatic bruits | Size and tenderness may suggest the severity of liver disease and may require additional evaluation. |

Download Table 1: Key Elements of Patient History and Physical Examination Printable PDF

Mental Health, Substance Use, and Adherence

Mental health: Mental health disorders are not contraindications to treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs). Strategies to overcome mental health-related barriers to successful HCV treatment include counseling, education, and referral to psychiatry and behavioral health services. Patients with mental health disorders may need increased attention to management of adverse effects and coordination of care during HCV treatment. An integrated care model in which mental health care providers provide HCV treatment and risk-reduction counseling has been effective Sackey, et al. 2018; Groessl, et al. 2013. Few data are currently available regarding the effect of an existing psychiatric diagnosis on patient adherence to any oral HCV treatment regimen.

With interferon-free regimens, depression is no longer a common adverse effect of HCV treatment. However, antidepressant and antipsychotic drug-drug interactions have been reported with DAAs, so monitoring is necessary; see Table 1: Key Elements of Patient History and Physical Examination for resources for identifying drug-drug interactions. Similarly, it is important to be aware of patient use of nonprescription medication. St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), an herbal self-remedy for depression, may decrease the effectiveness of DAA therapy FDA 2019; FDA 2017; FDA 2016.

Substance use: A history of or active use of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and other substances is not a contraindication to HCV treatment unless the drug or alcohol use significantly interferes with adherence to medications or appointments. Studies have demonstrated that individuals who are receiving substance use treatment can be effectively treated for chronic HCV infection Coffin, et al. 2019; Grebely, et al. 2018; Tsui, et al. 2016.

Once a patient’s alcohol consumption habits have been assessed, counseling may help the patient reduce or eliminate alcohol use. It is important for patients with HCV who use alcohol to be made aware of the effects of alcohol on the course of HCV disease. Alcohol use has been associated with increased rates of liver disease progression and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in people with chronic HCV. Moderate alcohol intake is associated with an increased risk of fibrosis progression Westin, et al. 2002, and light-to-moderate alcohol intake is associated with an increased risk of HCC in patients with compensated cirrhosis Vandenbulcke, et al. 2016. There is no consensus on a safe level of alcohol ingestion for people with chronic HCV.

Barriers to adherence: The purpose of the adherence assessment is to optimize support, not to deny access to treatment. After the pretreatment assessment and before treatment initiation, a plan can be developed with the patient to address potential barriers and put support resources in place Al-Khazraji, et al. 2020. Support groups and peer programs can promote increased patient engagement.

| KEY POINTS |

|

Baseline Laboratory Testing

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype may influence the choice of direct-acting antiviral regimen and treatment duration in patients with chronic HCV; however, given the availability of pangenotypic regimens, genotyping is not required to initiate treatment in treatment-naive patients. Baseline genotyping may also help in understanding treatment options if a sustained viral response is not attained because it may help distinguish reinfection from virologic relapse.

There are 6 common HCV genotypes Chevaliez and Pawlotsky 2007. Based on data from 8,140 participants (≥18 years old) in the U.S.-based Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study, genotype 1 was most common (75.4%), followed by genotypes 2 (12.6%) and 3 (10.2%); genotypes 4 (1.5%) and 6 (0.3%) were less prevalent Gordon, et al. 2019. The single participant with genotype 5 was excluded from the study. Distribution varied significantly by geography and demographics; birth decade, race, and study site were independently associated with genotype distribution (P < 0.01).

Additional baseline laboratory testing essential to pre-HCV treatment is listed in Table 2, below.

| Table 2: Pretreatment Laboratory Testing |

|

| Abbreviations: anti-HBc, hepatitis B core antibody; anti-HBs, hepatitis B surface antibody; ART, antiretroviral therapy; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G; INR, international normalized ratio.

Notes:

|

|

| Test | Clinical Note |

| Quantitative HCV RNA | Confirms active HCV infection and determines HCV viral load. |

| Genotype/subtype | Genotype and subtype guide choice of regimen. |

| Complete blood count |

|

| Serum electrolytes with creatinine |

|

| Hepatic function panel |

|

| INR | Elevated INR suggests decompensated cirrhosis. |

| Pregnancy test for all individuals of childbearing potential | If patient is pregnant, suggest treatment deferral [a]. |

| HAV antibodies | Obtain HAV antibody test (IgG or total) and administer the full HAV vaccine series in patients not immune to HAV. |

| HBV antibodies |

|

| HIV test if status is unknown | If HIV infection is confirmed, offer the patient antiretroviral therapy [b]. |

| Urinalysis | Protein may suggest extrahepatic manifestation of HCV. |

| Fibrosis serum markers | If not previously evaluated by biopsy or FibroScan. |

Download Table 2: Pretreatment Laboratory Testing Printable PDF

Fibrosis Assessment

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Fibrosis Assessment

|

Abbreviations: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; RBV, ribavirin. |

Fibrosis stage predicts HCV treatment response Ogawa, et al. 2015. An assessment of the degree of fibrosis should be performed regardless of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) patterns because significant fibrosis may be present in patients with repeatedly normal ALT EASL 2020. In 1 study, approximately 50% of people with HCV born between 1945 and 1965 had severe fibrosis or cirrhosis as measured by Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) index scoring Klevens, et al. 2016. It is particularly important to identify patients with bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis; these findings may influence treatment selection and duration and may dictate post-treatment follow-up, such as the need for ongoing assessment for esophageal varices, hepatic function, and surveillance monitoring for HCC AASLD/IDSA 2021; Bruix and Sherman 2011; Garcia-Tsao, et al. 2007. Patients known to have cirrhosis do not require repeat determination of the degree of fibrosis before treatment.

Fibrosis stage can be assessed using noninvasive modalities, such as transient elastography, aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index (APRI), FIB-4 index, and assays of direct markers of liver fibrosis (see Table 3, below). Noninvasive modalities are well suited for rapid pretreatment assessment of chronic HCV infection in the primary care setting. Indirect serum markers use mathematical algorithms with different variables to predict fibrosis and are easily accessible in the primary care setting. Tests such as the APRI and FIB-4 index (age, AST, ALT, platelet count) appear efficacious in patients with little or no fibrosis and those with cirrhosis. However, these tests have limited ability to discriminate between intermediate stages of fibrosis Castera, et al. 2014; Patel and Shackel 2014; Schiavon Lde, et al. 2014. Several studies have found the FIB-4 index to predict fibrosis more accurately than the APRI Amorim, et al. 2012; Shaikh, et al. 2009.

Liver biopsies are not routinely required but are useful for patients with highly discordant results on noninvasive testing and in patients suspected of having a second etiology for liver disease in addition to HCV infection. Liver biopsy is an important instrument for diagnosing concurrent diseases, such as metabolic nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, hemochromatosis, autoimmune primary biliary cholangitis, and autoimmune hepatitis. Although liver biopsy is safe and has a very low risk of complications, invasive procedures may be difficult to obtain in a timely fashion or unacceptably costly for uninsured patients Seeff, et al. 2010.

An APRI calculator, FIB-4 index calculator, and other online clinical tools are available at Hepatitis C Online. Assays of direct markers of liver fibrosis measure various combinations of liver matrix components in combination with standard biochemical markers. These assays (FibroSure, FibroTest, FibroMeter, FIBROSpect II, and HepaScore) appear efficacious in patients with little or no fibrosis and those with cirrhosis, but, like the FIB-4 index and APRI, these assays have limited ability to discriminate between intermediate stages of fibrosis Castera, et al. 2014; Patel and Shackel 2014; Schiavon Lde, et al. 2014. These tests will provide an indication of disease progression over time and can be helpful in counseling patients who are considering treatment Poynard, et al. 2014.

Vibration-controlled transient elastography (VCTE) measures shear wave velocity (expressed in kilopascals) and assesses a larger volume of liver parenchyma than liver biopsy. VCTE is most efficacious in F0 to F1 and F4 fibrosis but may be difficult to interpret in F2 and F3 disease Loomba, et al. 2023; Tapper, et al. 2015; Castera, et al. 2014; Schiavon Lde, et al. 2014; Verveer, et al. 2012. Although VCTE is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, it is not yet available in all settings and, although highly accurate, is not as cost-effective as laboratory liver fibrosis determinations Schmid, et al. 2015. There may also be limitations for patients with obesity Lai and Afdhal 2019. Other technologies, such as acoustic radiation force imaging, portal venous transit time, and magnetic resonance imaging elastography or a combination of modalities, show promise for possible future use; these procedures are not recommended at this time because of their lack of sensitivity and specificity in early fibrosis, high cost, and limited availability EASL 2020; Agbim and Asrani 2019; Bohte, et al. 2014.

| Table 3: Methods for Staging Fibrosis | |||

| Abbreviations: APRI, aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index; FIB-4, Fibrosis-4; VCTE, vibration-controlled transient elastography.

Note:

|

|||

| Method | Procedure | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Indirect serum markers | APRI, FIB-4 [a] |

|

Limited ability to differentiate intermediate stages of fibrosis |

| Direct markers | FibroSure, FibroTest, FibroMeter, FIBROSpect II, and HepaScore |

|

Limited ability to differentiate intermediate stages of fibrosis |

| VCTE | Shear wave velocity |

|

|

| Liver biopsy | Pathologic examination |

|

|

Cirrhosis Evaluation

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Cirrhosis Evaluation

|

Abbreviations: CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; CT, computerized axial tomography; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. |

The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score (MELD calculator) or the CTP score (see Table 4, below) may be used to classify the severity of cirrhosis.

| Table 4: Calculating the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP) Score for Severity of Cirrhosis [a] | |||

Notes:

|

|||

| 1 point [b] | 2 points [b] | 3 points [b] | |

| Encephalopathy | None | Stage 1 to 2 (or precipitant-induced) |

Stage 3 to 4 (or chronic) |

| Ascites | None | Mild/moderate (diuretic-responsive) |

Severe (diuretic-refractory) |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | <2.0 | 2.0 to 3.0 | >3.0 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | >3.5 | 2.8 to 3.5 | <2.8 |

| Prothrombin time (sec prolonged) or international normalized ratio (INR) | <4.0 | 4.0 to 6.0 | >6.0 |

| <1.7 | 1.7 to 2.3 | >2.3 | |

Assessment for decompensation in patients with cirrhosis can be accomplished through medical history-taking and initial laboratory testing (see Table 5, below). Decompensation is defined as a MELD score of >15 or the presence of ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, portal hypertensive bleeding, HCC, intractable pruritus, hepatopulmonary syndrome, coagulopathy, or portopulmonary hypertension Fox and Brown 2012. Because of the clinical complexity of the condition, patients with a history or presence of decompensated cirrhosis should be referred to a liver disease specialist.

All patients with cirrhosis should undergo an upper endoscopy to screen for the presence of esophageal varices. Patients with HCV-related bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis are at increased risk of developing primary HCC and should undergo surveillance with an ultrasound every 6 months Shoreibah, et al. 2014; Bruix and Sherman 2011. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) testing lacks adequate sensitivity and specificity for effective use in surveillance and diagnosis of HCC. Elevated AFP levels may be seen in HCV infection in the absence of HCC EASL 2018; El-Serag and Mason 1999.

For additional risk stratification and diagnosis information, see the American Association of the Study for Liver Diseases practice guidance on portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis Garcia-Tsao, et al. 2017.

| Table 5: Baseline Evaluation and Follow-Up Screening for Patients With Cirrhosis | |

| Abbreviations: CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MELD, Model of End-Stage Liver Disease. | |

| Type of Evaluation | Rationale |

| Assess for decompensation; refer to a liver disease specialist if history of or current decompensation | Decompensation is defined as the presence (or history) of 1 of the following:

|

| Abdominal ultrasound to screen for HCC | Ongoing HCC surveillance should be performed for patients with bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis every 6 to 12 months. |

| Upper endoscopy | Refer to a liver disease specialist to screen for varices. |

Renal, HAV/HBV, Metabolic, and Cardiovascular Status

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Renal Status

HAV and HBV Immunity Status

|

Abbreviations: anti-HBc, hepatitis B core antibody; anti-HBs, hepatitis B surface antibody; CrCl, creatinine clearance; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G. |

Renal status: A patient’s renal status will influence the choice of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) regimen. Evaluation for renal disease includes assessing HCV-related causes of kidney disease, such as membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis and membranous glomerulonephritis, even if patients have other comorbidities also associated with kidney disease, such as diabetes and hypertension.

HAV and HBV immunity status: Completion of HAV and HBV vaccination is not a pretreatment mandate and is appropriate during or after treatment for chronic HCV infection. Coinfection with HCV and either HAV or HBV may result in additional liver inflammation and pathology; vaccination against HAV and HBV is important for patients with HCV to prevent acute decompensation and the sequelae of chronic superinfection by HBV Lau and Hewlett 2005. Approximately 40% to 50% of patients with HCV have no documented immunity against HAV or HBV Henkle, et al. 2015.

If a patient is susceptible to both HAV and HBV infection, the combined vaccine series should be initiated.

The laboratory assessment and vaccination (as appropriate) for HAV and HBV should be performed as soon as possible, but completion of the vaccine series is not necessary before initiation of HCV treatment.

Vaccination of patients with positive anti-HBc and negative HBsAg and anti-HBs (i.e., isolated anti-HBc) test results is controversial because results are subject to several interpretations. In patients from regions where HBV infection is highly endemic or in patients with risk factors for acquiring HBV, a positive anti-HBc result may represent acute or chronic active HBV or serologic clearance of anti-HBs after a prior infection. In patients who have no risk factors or are from regions where HBV infection rates are low, a positive anti-HBc result may represent a false-positive result. In patients with isolated anti-HBc, HBV DNA testing to assess for active HBV infection is recommended, with subsequent vaccination if results are negative.

HBV reactivation and HBV-related hepatic flares, sometimes fulminant, have been reported both during and after DAA therapy in patients who were not receiving concurrent HBV treatment Butt, et al. 2018; Belperio, et al. 2017; Wang, et al. 2017; De Monte, et al. 2016; Hayashi, et al. 2016; Sulkowski, et al. 2016; Takayama, et al. 2016; Collins, et al. 2015; Ende, et al. 2015. Studies have demonstrated that HCV has a suppressive effect on HBV replication. For more information about the risk of HBV reactivation, see the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Drug Safety Communication.

| KEY POINT |

|

Metabolic status: Obesity does not affect the treatment of HCV with DAAs. Among individuals with HCV, both obesity and hepatic steatosis have been associated with progression of fibrosis, increased risk of advanced liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Minami, et al. 2021; Dyal, et al. 2015; Goossens and Negro 2014; Charlton, et al. 2006; Bressler, et al. 2003.

Chronic HCV infection appears to be associated with an increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) in predisposed individuals Lecube, et al. 2004; Mehta, et al. 2003; Mehta, et al. 2000. Insulin resistance (IR) and diabetes are associated with increased liver fibrosis Patel, et al. 2011; Moucari, et al. 2008; Petta, et al. 2008, cirrhosis Gordon, et al. 2015, and HCC Hung, et al. 2011; Donadon, et al. 2009; Veldt, et al. 2008; Tazawa, et al. 2002 in patients with HCV. Successful treatment of chronic HCV infection may be associated with improved IR, reduced incidence of DM2, and potentially decreased DM2-associated renovascular complications Hsu, et al. 2014; Thompson, et al. 2012; Arase, et al. 2009. No serious drug-drug interactions have been reported with DAA agents and insulin-sensitizing or diabetic medications. However, because of the potential for improved glycemic control, diabetic patients have a higher risk for hypoglycemia during or after treatment with DAAs Zhou, et al. 2022; Andres, et al. 2020; Yuan, et al. 2020; Li(b), et al. 2019; Li(a), et al. 2019 and should be counseled to monitor blood sugars during and after treatment.

Cardiovascular status: Although cardiovascular disease and congestive heart failure may be worsened by possible anemia associated with the use of ribavirin (RBV)-containing regimens, no such concern is noted with DAA regimens that do not contain RBV. However, drug-drug interactions between DAA medications and cardiovascular medications have been reported and may require adjustments or changes before initiation of therapy.

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS: PRETREATMENT ASSESSMENT IN ADULTS WITH CHRONIC HCV INFECTION |

Medical History and Physical Examination

Fibrosis Assessment

Cirrhosis Evaluation

Renal Status

HAV and HBV Immunity Status

|

Abbreviations: anti-HBc, hepatitis B core antibody; anti-HBs, hepatitis B surface antibody; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; CrCl, creatinine clearance; CT, computerized axial tomography; DAA, direct-acting antiviral; HAV, hepatitis A virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IgG, immunoglobulin G; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging. |

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

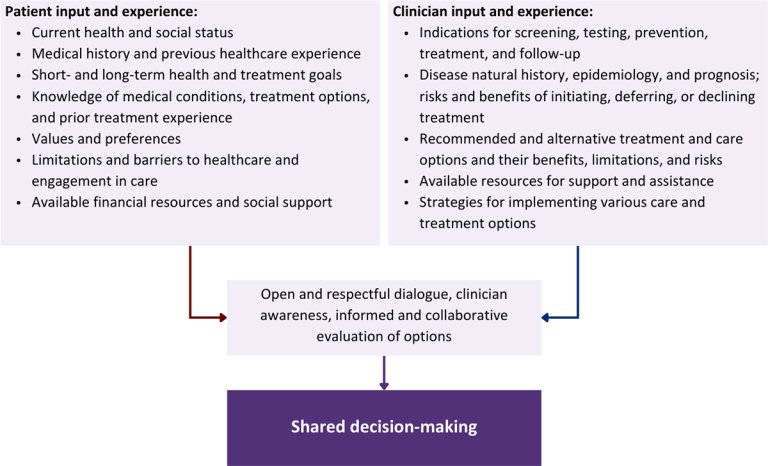

Rationale

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

AASLD/IDSA. Hepatitis C guidance: AASLD-IDSA recommendations for testing, managing, and treating adults infected with hepatitis C virus. 2021 Oct. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/ [accessed 2022 Aug 29]

Agbim U., Asrani S. K. Non-invasive assessment of liver fibrosis and prognosis: an update on serum and elastography markers. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;13(4):361-74. [PMID: 30791772]

Al-Khazraji A., Patel I., Saleh M., et al. Identifying barriers to the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. Dig Dis 2020;38(1):46-52. [PMID: 31422405]

Amorim T. G., Staub G. J., Lazzarotto C., et al. Validation and comparison of simple noninvasive models for the prediction of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Ann Hepatol 2012;11(6):855-61. [PMID: 23109448]

Andres J., Barros M., Arutunian M., et al. Treatment of hepatitis C virus and long-term effect on glycemic control. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2020;26(6):775-81. [PMID: 32463777]

Arase Y., Suzuki F., Suzuki Y., et al. Sustained virological response reduces incidence of onset of type 2 diabetes in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2009;49(3):739-44. [PMID: 19127513]

Belperio P. S., Shahoumian T. A., Mole L. A., et al. Evaluation of hepatitis B reactivation among 62,920 veterans treated with oral hepatitis C antivirals. Hepatology 2017;66(1):27-36. [PMID: 28240789]

Bohte A. E., de Niet A., Jansen L., et al. Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis: a comparison of ultrasound-based transient elastography and MR elastography in patients with viral hepatitis B and C. Eur Radiol 2014;24(3):638-48. [PMID: 24158528]

Bressler B. L., Guindi M., Tomlinson G., et al. High body mass index is an independent risk factor for nonresponse to antiviral treatment in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2003;38(3):639-44. [PMID: 12939590]

Bruix J., Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology 2011;53(3):1020-22. [PMID: 21374666]

Butt A. A., Yan P., Shaikh O. S., et al. Hepatitis B reactivation and outcomes in persons treated with directly acting antiviral agents against hepatitis C virus: results from ERCHIVES. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47(3):412-20. [PMID: 29181838]

Castera L., Winnock M., Pambrun E., et al. Comparison of transient elastography (FibroScan), FibroTest, APRI and two algorithms combining these non-invasive tests for liver fibrosis staging in HIV/HCV coinfected patients: ANRS CO13 HEPAVIH and FIBROSTIC Collaboration. HIV Med 2014;15(1):30-39. [PMID: 24007567]

Charlton M. R., Pockros P. J., Harrison S. A. Impact of obesity on treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2006;43(6):1177-86. [PMID: 16729327]

Chevaliez S., Pawlotsky J. M. Hepatitis C virus: virology, diagnosis and management of antiviral therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13(17):2461-66. [PMID: 17552030]

Coffin P. O., Santos G. M., Behar E., et al. Randomized feasibility trial of directly observed versus unobserved hepatitis C treatment with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir among people who inject drugs. PLoS One 2019;14(6):e0217471. [PMID: 31158245]

Collins J. M., Raphael K. L., Terry C., et al. Hepatitis B virus reactivation during successful treatment of hepatitis C virus with sofosbuvir and simeprevir. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(8):1304-6. [PMID: 26082511]

De Monte A., Courjon J., Anty R., et al. Direct-acting antiviral treatment in adults infected with hepatitis C virus: reactivation of hepatitis B virus coinfection as a further challenge. J Clin Virol 2016;78:27-30. [PMID: 26967675]

Donadon V., Balbi M., Zanette G. Hyperinsulinemia and risk for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver diseases and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009;3(5):465-67. [PMID: 19817667]

Dyal H. K., Aguilar M., Bhuket T., et al. Concurrent obesity, diabetes, and steatosis increase risk of advanced fibrosis among HCV patients: a systematic review. Dig Dis Sci 2015;60(9):2813-24. [PMID: 26138651]

EASL. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018;69(1):182-236. [PMID: 29628281]

EASL. EASL recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C: final update of the series. J Hepatol 2020;73(5):1170-1218. [PMID: 32956768]

Ebell M. H. Probability of cirrhosis in patients with hepatitis C. Am Fam Physician 2003;68(9):1831-33. [PMID: 14620604]

El-Serag H. B., Mason A. C. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med 1999;340(10):745-50. [PMID: 10072408]

Ende A. R., Kim N. H., Yeh M. M., et al. Fulminant hepatitis B reactivation leading to liver transplantation in a patient with chronic hepatitis C treated with simeprevir and sofosbuvir: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2015;9:164. [PMID: 26215390]

FDA. Epclusa (sofosbuvir and velpatasvir) tablets, for oral use. 2016 Jun. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2016/208341s000lbl.pdf [accessed 2022 Feb 1]

FDA. Vosevi (sofosbuvir, velpatasvir, and voxilaprevir) tablets, for oral use. 2017 Jul. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/209195s000lbl.pdf [accessed 2022 Feb 1]

FDA. Harvoni (ledipasvir and sofosbuvir) tablets, for oral use. 2019 Aug. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/212477s000lbl.pdf [accessed 2022 Feb 1]

Fox A. N., Brown R. S. Is the patient a candidate for liver transplantation?. Clin Liver Dis 2012;16(2):435-48. [PMID: 22541708]

Garcia-Tsao G., Abraldes J. G., Berzigotti A., et al. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: risk stratification, diagnosis, an management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2017;65(1):310-35. [PMID: 27786365]

Garcia-Tsao G., Sanyal A. J., Grace N. D., et al. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology 2007;46(3):922-38. [PMID: 17879356]

Ghany M. G., Morgan T. R. Hepatitis C guidance 2019 update: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases-Infectious Diseases Society of America recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 2020;71(2):686-721. [PMID: 31816111]

Goossens N., Negro F. The impact of obesity and metabolic syndrome on chronic hepatitis C. Clin Liver Dis 2014;18(1):147-56. [PMID: 24274870]

Gordon S. C., Lamerato L. E., Rupp L. B., et al. Prevalence of cirrhosis in hepatitis C patients in the Chronic Hepatitis Cohort Study (CHeCS): a retrospective and prospective observational study. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110(8):1169-77; quiz 1178. [PMID: 26215529]

Gordon S. C., Trudeau S., Li J., et al. Race, age, and geography impact hepatitis C genotype distribution in the United States. J Clin Gastroenterol 2019;53(1):40-50. [PMID: 28737649]

Gountas I., Sypsa V., Blach S., et al. HCV elimination among people who inject drugs. Modelling pre- and post-WHO elimination era. PLoS One 2018;13(8):e0202109. [PMID: 30114207]

Granozzi B., Guardigni V., Badia L., et al. Out-of-hospital treatment of hepatitis C increases retention in care among people who inject drugs and homeless persons: an observational study. J Clin Med 2021;10(21):4955. [PMID: 34768474]

Grebely J., Dalgard O., Conway B., et al. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for hepatitis C virus infection in people with recent injection drug use (SIMPLIFY): an open-label, single-arm, phase 4, multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;3(3):153-61. [PMID: 29310928]

Groessl E. J., Sklar M., Cheung R. C., et al. Increasing antiviral treatment through integrated hepatitis C care: a randomized multicenter trial. Contemp Clin Trials 2013;35(2):97-107. [PMID: 23669414]

Hajarizadeh B., Cunningham E. B., Valerio H., et al. Hepatitis C reinfection after successful antiviral treatment among people who inject drugs: a meta-analysis. J Hepatol 2020;72(4):643-57. [PMID: 31785345]

Hayashi K., Ishigami M., Ishizu Y., et al. A case of acute hepatitis B in a chronic hepatitis C patient after daclatasvir and asunaprevir combination therapy: hepatitis B virus reactivation or acute self-limited hepatitis?. Clin J Gastroenterol 2016;9(4):252-56. [PMID: 27329484]

Henkle E., Lu M., Rupp L. B., et al. Hepatitis A and B immunity and vaccination in chronic hepatitis B and C patients in a large United States cohort. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60(4):514-22. [PMID: 25371489]

Hsu Y. C., Wu C. Y., Lane H. Y., et al. Determinants of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients treated with nucleos(t)ide analogues for chronic hepatitis B. J Antimicrob Chemother 2014;69(7):1920-27. [PMID: 24576950]

Hung C. H., Lee C. M., Wang J. H., et al. Impact of diabetes mellitus on incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis C patients treated with interferon-based antiviral therapy. Int J Cancer 2011;128(10):2344-52. [PMID: 20669224]

Jalan R., Fernandez J., Wiest R., et al. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: a position statement based on the EASL Special Conference 2013. J Hepatol 2014;60(6):1310-24. [PMID: 24530646]

Kaul V. V., Munoz S. J. Coagulopathy of liver disease. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2000;3(6):433-38. [PMID: 11096602]

Klevens R. M., Canary L., Huang X., et al. The burden of hepatitis C infection-related liver fibrosis in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63(8):1049-55. [PMID: 27506688]

Lai M., Afdhal N. H. Liver fibrosis determination. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2019;48(2):281-89. [PMID: 31046975]

Lau D. T., Hewlett A. T. Screening for hepatitis A and B antibodies in patients with chronic liver disease. Am J Med 2005;118 Suppl 10A:28s-33s. [PMID: 16271538]

Lecube A., Hernandez C., Genesca J., et al. High prevalence of glucose abnormalities in patients with hepatitis C virus infection: a multivariate analysis considering the liver injury. Diabetes Care 2004;27(5):1171-75. [PMID: 15111540]

Li(a) J., Gordon S. C., Rupp L. B., et al. Sustained virological response does not improve long-term glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int 2019;39(6):1027-32. [PMID: 30570808]

Li(b) J., Gordon S. C., Rupp L. B., et al. Sustained virological response to hepatitis C treatment decreases the incidence of complications associated with type 2 diabetes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2019;49(5):599-608. [PMID: 30650468]

Loomba R., Huang D. Q., Sanyal A. J., et al. Liver stiffness thresholds to predict disease progression and clinical outcomes in bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis. Gut 2023;72(3):581-89. [PMID: 36750244]

Mehta S. H., Brancati F. L., Strathdee S. A., et al. Hepatitis C virus infection and incident type 2 diabetes. Hepatology 2003;38(1):50-56. [PMID: 12829986]

Mehta S. H., Brancati F. L., Sulkowski M. S., et al. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus among persons with hepatitis C virus infection in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2000;133(8):592-99. [PMID: 11033586]

Minami T., Tateishi R., Fujiwara N., et al. Impact of obesity and heavy alcohol consumption on hepatocellular carcinoma development after HCV eradication with antivirals. Liver Cancer 2021;10(4):309-19. [PMID: 34414119]

Moucari R., Asselah T., Cazals-Hatem D., et al. Insulin resistance in chronic hepatitis C: association with genotypes 1 and 4, serum HCV RNA level, and liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology 2008;134(2):416-23. [PMID: 18164296]

Ogawa E., Furusyo N., Shimizu M., et al. Non-invasive fibrosis assessment predicts sustained virological response to telaprevir with pegylated interferon and ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C. Antivir Ther 2015;20(2):185-92. [PMID: 24941012]

Patel K., Shackel N. A. Current status of fibrosis markers. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2014;30(3):253-59. [PMID: 24671009]

Patel K., Thompson A. J., Chuang W. L., et al. Insulin resistance is independently associated with significant hepatic fibrosis in Asian chronic hepatitis C genotype 2 or 3 patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;26(7):1182-88. [PMID: 21410752]

Petta S., Camma C., Di Marco V., et al. Insulin resistance and diabetes increase fibrosis in the liver of patients with genotype 1 HCV infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103(5):1136-44. [PMID: 18477344]

Poynard T., Vergniol J., Ngo Y., et al. Staging chronic hepatitis C in seven categories using fibrosis biomarker (FibroTest) and transient elastography (FibroScan(R)). J Hepatol 2014;60(4):706-14. [PMID: 24291240]

Sackey B., Shults J. G., Moore T. A., et al. Evaluating psychiatric outcomes associated with direct-acting antiviral treatment in veterans with hepatitis C infection. Ment Health Clin 2018;8(3):116-21. [PMID: 29955556]

Schiavon Lde L., Narciso-Schiavon J. L., de Carvalho-Filho R. J. Non-invasive diagnosis of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20(11):2854-66. [PMID: 24659877]

Schmid P., Bregenzer A., Huber M., et al. Progression of liver fibrosis in HIV/HCV co-infection: a comparison between non-invasive assessment methods and liver biopsy. PLoS One 2015;10(9):e0138838. [PMID: 26418061]

Seeff L. B., Everson G. T., Morgan T. R., et al. Complication rate of percutaneous liver biopsies among persons with advanced chronic liver disease in the HALT-C trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8(10):877-83. [PMID: 20362695]

Shaikh S., Memon M. S., Ghani H., et al. Validation of three non-invasive markers in assessing the severity of liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2009;19(8):478-82. [PMID: 19651008]

Shoreibah M. G., Bloomer J. R., McGuire B. M., et al. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma: evidence, guidelines and utilization. Am J Med Sci 2014;347(5):415-19. [PMID: 24759379]

Simmons B., Saleem J., Heath K., et al. Long-term treatment outcomes of patients infected with hepatitis C virus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the survival benefit of achieving a sustained virological response. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(5):730-40. [PMID: 25987643]

Sulkowski M. S., Chuang W. L., Kao J. H., et al. No evidence of reactivation of hepatitis B virus among patients treated with ledipasvir-sofosbuvir for hepatitis C virus infection. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63(9):1202-4. [PMID: 27486112]

Takayama H., Sato T., Ikeda F., et al. Reactivation of hepatitis B virus during interferon-free therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir in patient with hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus co-infection. Hepatol Res 2016;46(5):489-91. [PMID: 26297529]

Tapper E. B., Castera L., Afdhal N. H. FibroScan (vibration-controlled transient elastography): where does it stand in the United States practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13(1):27-36. [PMID: 24909907]

Tazawa J., Maeda M., Nakagawa M., et al. Diabetes mellitus may be associated with hepatocarcinogenesis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Dig Dis Sci 2002;47(4):710-15. [PMID: 11991597]

Thompson A. J., Patel K., Chuang W. L., et al. Viral clearance is associated with improved insulin resistance in genotype 1 chronic hepatitis C but not genotype 2/3. Gut 2012;61(1):128-34. [PMID: 21873466]

Torrens M., Soyemi T., Bowman D., et al. Beyond clinical outcomes: the social and healthcare system implications of hepatitis C treatment. BMC Infect Dis 2020;20(1):702. [PMID: 32972393]

Tsui J. I., Williams E. C., Green P. K., et al. Alcohol use and hepatitis C virus treatment outcomes among patients receiving direct antiviral agents. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;169:101-9. [PMID: 27810652]

Vandenbulcke H., Moreno C., Colle I., et al. Alcohol intake increases the risk of HCC in hepatitis C virus-related compensated cirrhosis: a prospective study. J Hepatol 2016;65(3):543-51. [PMID: 27180899]

Veldt B. J., Chen W., Heathcote E. J., et al. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology 2008;47(6):1856-62. [PMID: 18506898]

Verveer C., Zondervan P. E., ten Kate F. J., et al. Evaluation of transient elastography for fibrosis assessment compared with large biopsies in chronic hepatitis B and C. Liver Int 2012;32(4):622-28. [PMID: 22098684]

Wang C., Ji D., Chen J., et al. Hepatitis due to reactivation of hepatitis B virus in endemic areas among patients with hepatitis C treated with direct-acting antiviral agents. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15(1):132-36. [PMID: 27392759]

Westin J., Lagging L. M., Spak F., et al. Moderate alcohol intake increases fibrosis progression in untreated patients with hepatitis C virus infection. J Viral Hepat 2002;9(3):235-41. [PMID: 12010513]

Yuan M., Zhou J., Du L., et al. Hepatitis C virus clearance with glucose improvement and factors affecting the glucose control in chronic hepatitis C patients. Sci Rep 2020;10(1):1976. [PMID: 32029793]

Zhou Y., Xie W., Zheng C., et al. Hypoglycemia associated with direct-acting anti-hepatitis C virus drugs: an epidemiologic surveillance study of the FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2022;96(5):690-97. [PMID: 34913180]

Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines

| Updates, Authorship, and Related Guidelines | |

| Date of original publication | October 06, 2022 |

| Date of current publication | October 06, 2022 |

| Highlights of changes, additions, and updates in the October 06, 2022 edition |

|

| Intended users | Clinicians in New York State who treat adults with chronic HCV |

| Lead author |

Christine A. Kerr, MD |

| Writing group |

Joshua S. Aron, MD; David E. Bernstein, MD; Colleen Flanigan, RN, MS; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD |

| Author and writing group conflict of interest disclosures | There are no author or writing group conflict of interest disclosures |

| Committee | |

| Developer and funder |

New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) |

| Development process |

See Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings Scheme, below. |

| Related NYSDOH AI guidelines | |

Guideline Development and Recommendation Ratings

| Guideline Development: New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute Clinical Guidelines Program | |

| Program manager | Clinical Guidelines Program, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases. See Program Leadership and Staff. |

| Mission | To produce and disseminate evidence-based, state-of-the-art clinical practice guidelines that establish uniform standards of care for practitioners who provide prevention or treatment of HIV, viral hepatitis, other sexually transmitted infections, and substance use disorders for adults throughout New York State in the wide array of settings in which those services are delivered. |

| Expert committees | The NYSDOH AI Medical Director invites and appoints committees of clinical and public health experts from throughout New York State to ensure that the guidelines are practical, immediately applicable, and meet the needs of care providers and stakeholders in all major regions of New York State, all relevant clinical practice settings, key New York State agencies, and community service organizations. |

| Committee structure |

|

| Disclosure and management of conflicts of interest |

|

| Evidence collection and review |

|

| Recommendation development |

|

| Review and approval process |

|

| External reviews |

|

| Update process |

|

| Recommendation Ratings Scheme | |||

| Strength | Quality of Evidence | ||

| Rating | Definition | Rating | Definition |

| A | Strong | 1 | Based on published results of at least 1 randomized clinical trial with clinical outcomes or validated laboratory endpoints. |

| B | Moderate | * | Based on either a self-evident conclusion; conclusive, published, in vitro data; or well-established practice that cannot be tested because ethics would preclude a clinical trial. |

| C | Optional | 2 | Based on published results of at least 1 well-designed, nonrandomized clinical trial or observational cohort study with long-term clinical outcomes. |

| 2† | Extrapolated from published results of well-designed studies (including nonrandomized clinical trials) conducted in populations other than those specifically addressed by a recommendation. The source(s) of the extrapolated evidence and the rationale for the extrapolation are provided in the guideline text. One example would be results of studies conducted predominantly in a subpopulation (e.g., one gender) that the committee determines to be generalizable to the population under consideration in the guideline. | ||

| 3 | Based on committee expert opinion, with rationale provided in the guideline text. | ||

Last updated on January 17, 2024