Purpose of This Guideline

Date of current publication: October 2, 2023

Lead author: Yonina Mar, MD

Writing group: Susan D. Whitley, MD; Timothy J. Wiegand, MD; Sharon L. Stancliff, MD; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH

Committee: Substance Use Guidelines Committee

Date of original publication: July 2020

This guideline on the treatment of alcohol use disorder (AUD) was developed by the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute (NYSDOH AI) to provide clinical guidance for practitioners who provide medical care for adults in New York State.

This guideline aims to:

- Increase clinicians’ awareness of the risks associated with AUD of any severity and the benefits of diagnosing and treating AUD in adults

- Increase clinicians’ knowledge of available evidence-based treatments for AUD and withdrawal management and increase the availability of AUD treatment in ambulatory care settings in New York State

- Promote a harm reduction approach to AUD treatment through implementation of practical strategies for reducing the negative consequences associated with alcohol use (see NYSDOH AI guideline Substance Use Harm Reduction in Medical Care)

AUD is a medical condition characterized by an impaired ability to stop or control alcohol use despite adverse social, occupational, or health consequences. AUD, which has been referred to as alcohol abuse, alcohol dependence, alcohol addiction, and alcoholism, encompasses all and can be mild, moderate, or severe based on the number of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 criteria met NIAAA(a) 2023. The 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health in the United States reported that an estimated 28.6 million individuals aged 18 years or older in the United States had AUD in the past year SAMHSA 2023. Among people aged 12 years or older with AUD in the past year, 0.9% received pharmacologic AUD treatment during that period.

A wide range of negative health outcomes are associated with alcohol use in individuals with AUD or unhealthy alcohol use that does not meet the criteria for AUD. These include an increased risk of liver disease, heart disease, depression, stroke, and stomach bleeding; cancers of the oral cavity, esophagus, larynx, pharynx, colon, and rectum; difficulty managing diabetes, high blood pressure, pain, and sleep disorders; increased risk of drowning; and injuries from violence, falls, and motor vehicle crashes NIAAA(a) 2023; Bagnardi, et al. 2015; Grewal and Viswanathen 2012; Taylor and Rehm 2012; Taylor, et al. 2010; Baan, et al. 2007; Cherpitel 2007; Driscoll, et al. 2004.

In the United States, among individuals aged 16 years and older, the alcohol use-associated death rate increased by 50.9% between 1999 and 2017. In 2017, 2.6% of approximately 2.8 million deaths in the United States were associated with alcohol use, with liver disease and alcohol overdose or overdose with alcohol and other drugs accounting for nearly 50% White, et al. 2020. During the COVID-19 pandemic, observed AUD-related mortality rates were higher than projected rates, by 24.79% in 2020 and 21.95% in 2021, with the highest increase in AUD mortality observed in the youngest age group (25 to 44 years) Yeo, et al. 2022.

Role of primary care clinicians: Primary care clinicians in New York State can play an essential role in identifying and treating unhealthy alcohol use and AUD in their patients. The focus of this guideline is AUD treatment. Despite the prevalence of AUD and associated risks and the availability of effective outpatient treatment, AUD treatment declined from 2008 to 2017 Larsen, et al. 2022. Because primary care may lend itself to long-term relationships, this treatment setting is ideal for managing AUD as a chronic health condition.

Treatment Considerations

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Who to Treat

Treatment Goals and Selection

Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome

Follow-Up

|

Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; SUD, substance use disorder. Notes:

|

A combination of pharmacologic and behavioral treatment is the standard of care for patients with AUD Ray, et al. 2020; Anton, et al. 2006. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have demonstrated that both approaches, alone and in combination, can effectively reduce the frequency and quantity of alcohol use Bahji, et al. 2022; Ray, et al. 2020; Magill, et al. 2019; DiClemente, et al. 2017; Jonas, et al. 2014; Anton, et al. 2006. A retrospective cohort study found that pharmacologic treatment for AUD was associated with reduced incidence and progression of alcohol-associated liver disease Vannier, et al. 2022.

Treatment Goals

As with other chronic conditions, AUD treatment goals should be individualized and are likely to change over time. Clinicians and patients should discuss, agree on, and review AUD treatment goals regularly. If patients are unable to meet treatment goals, intensifying treatment with frequent visits, behavioral interventions, mental health assessment and treatment, and adjustment of dose or type of medication may be warranted.

A traditional goal of AUD treatment is long-term cessation of alcohol use, which may not be achievable for many individuals. Alternative treatment goals can lead to substantial improvements in the health and lives of those with AUD Witkiewitz, et al. 2021. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism research definition of recovery from AUD is a reflection of the shift to a non-abstinence-based AUD treatment approach:

“Recovery is a process through which an individual pursues both remission from AUD and cessation from heavy drinking. An individual may be considered ‘recovered’ if both remission from AUD and cessation from heavy drinking are achieved and maintained over time. For those experiencing alcohol-related functional impairment and other adverse consequences, recovery is often marked by the fulfillment of basic needs, enhancements in social support and spirituality, and improvements in physical and mental health, quality of life, and other dimensions of well-being. Continued improvement in these domains may, in turn, promote sustained recovery.” NIAAA(b) 2023

Harm reduction treatment goals may include the following:

- Staying engaged in care, which can facilitate prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of other conditions

- Reducing alcohol use

- Reducing high-risk behaviors (e.g., driving while intoxicated, engaging in condomless sex while drinking, using other substances while drinking, engaging in violent behavior toward intimate partners and others)

- Improving quality of life and other social indicators, such as employment, stable housing, and risk of incarceration

- Improving mental health

Treatment Selection

Clinicians should inform patients with AUD about all available pharmacologic and behavioral treatment options and all available treatment settings. The choice of treatment(s) is based on shared decision-making that considers individual goals, needs, and preferences; evidence-based treatment recommendations; resources; and other factors.

Pharmacologic treatment: Currently, 3 medications are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of AUD: acamprosate, naltrexone, and disulfiram. Gabapentin and topiramate are additional evidence-based options for treatment. All of these medications are available in oral formulations, and naltrexone is also available in an extended-release (XR) formulation for intramuscular injection (see guideline sections Preferred Pharmacologic Treatment and Alternative Pharmacologic Treatment). Recent study results suggest that treatment with hallucinogenic (e.g., psilocybin) and dissociative (e.g., ketamine) agents in conjunction with psychotherapy may decrease the percentage of heavy drinking days and increase days abstinent from alcohol Bogenschutz, et al. 2022; Calleja-Conde, et al. 2022; Garel, et al. 2022; Grabski, et al. 2022. More research is needed to confirm the benefits of these treatments for AUD.

Adherence is essential for pharmacologic treatment to be effective, making pill burden an important practical consideration for clinicians. Acamprosate is dosed 3 times daily, with 2 pills required for each dose, oral naltrexone is formulated for single-tablet once-daily dosing, and XR naltrexone is administered every 28 days.

Behavioral treatment: Behavioral treatment is typically delivered in a specialty addiction treatment program. The most commonly used and effective AUD interventions include assessment, personalized feedback, motivational interviewing (MI), goal setting, planning and review of homework, problem-solving skills, and relapse prevention and management Nadkarni, et al. 2023. For a discussion of MI, contingency management, cognitive behavioral therapy, and other behavioral treatments for AUD, see the guideline section Behavioral Treatment.

Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome

Before initiating AUD treatment, clinicians should determine if patients are or are at risk of experiencing withdrawal syndrome. If symptoms are present, clinicians should assess withdrawal severity using a validated instrument, such as the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol, Revised (CIWA-Ar) or the self-completed 10-item Short Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (SAWS), which has been validated in the outpatient setting Muncie, et al. 2013; Elholm, et al. 2010; Gossop, et al. 2002; Sullivan, et al. 1989.

In individuals with AUD, abruptly ceasing or significantly reducing alcohol use can precipitate acute withdrawal syndrome within 4 to 12 hours of last alcohol use APA 2017. The syndrome may persist for as long as 5 days, with symptoms ranging from mild (anxiety, agitation, tremor, and sympathetic nervous system activation) to severe and life-threatening (seizure and delirium tremens) if untreated APA 2017. In most individuals, mild-to-moderate alcohol withdrawal syndrome can be managed in the outpatient primary care setting Muncie, et al. 2013 with benzodiazepines Schaefer and Hafner 2013; Mayo-Smith 1997. The Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) is a validated screening instrument for predicting the development of severe alcohol withdrawal. A PAWSS score < 4 is considered low risk for complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome and may help identify individuals that can be treated in the outpatient primary care setting Wood, et al. 2018; Maldonado, et al. 2015. For recommendations on treating alcohol withdrawal syndrome, see the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management 2020.

Gabapentin effectively treats common symptoms of acute and protracted alcohol withdrawal, including anxiety and sleep disturbances Mason, et al. 2018; Mason, et al. 2014. Gabapentin and other anticonvulsants, including carbamazepine and valproic acid, have been studied as alternatives to benzodiazepines for managing alcohol withdrawal syndrome Fluyau, et al. 2023; Anton, et al. 2020; Barrons and Roberts 2010; Myrick, et al. 2009; Bonnet, et al. 1999. These medications have less potential for misuse and may be safer, particularly if mixed with alcohol. Ideally, individuals treated for alcohol withdrawal syndrome in the outpatient setting are assessed daily until their withdrawal symptoms decrease, and the medication dosage is reduced and eventually discontinued. To increase the likelihood of success in the outpatient setting, patients should be able to take oral medications, be committed to frequent follow-up visits, or have a relative, friend, or caregiver who can stay with them and administer medication Blondell 2005.

Patients who experience severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms should be referred to a detoxification or inpatient setting for intensive management Myrick and Anton 1998 (see PAWSS for assessing the level of severity). Referral for intensive management of alcohol withdrawal may be appropriate for patients who have:

- A history of long-term heavy alcohol use

- Acute or chronic comorbidities, including serious or unstable medical or psychiatric comorbidities that require a high level of monitoring (e.g., severe coronary artery disease, hepatic or renal impairment, dementia, or risk for delirium)

- A history of withdrawal seizures or high risk of delirium tremens

- A concurrent SUD or use of other drugs, particularly benzodiazepines and opioids

See the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) Alcohol Withdrawal Management Guideline for detailed recommendations regarding levels of care.

Follow-Up

Frequent follow-up visits allow clinicians to provide support and encouragement and monitor treatment response, adverse effects, medication adherence, and signs of continued alcohol use or return to use. Follow-up within 2 weeks of treatment initiation allows tailoring of the treatment plan to individual needs (e.g., change in dose of pharmacologic treatment, addition of support services). As patients stabilize on treatment, monthly or at least quarterly follow-up allows for ongoing evaluation to ensure that treatment goals are being met.

Behavioral Treatment

| RECOMMENDATION |

Behavioral Treatment

|

Many studies support the effectiveness of motivational interviewing (MI), motivational enhancement therapy (MET), and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for treating individuals with AUD Miller 2018; DiClemente, et al. 2017; Lenz, et al. 2016; Lundahl, et al. 2013; Smedslund, et al. 2011; Lundahl, et al. 2010; Magill and Ray 2009, including studies conducted in the primary care setting VanBuskirk and Wetherell 2014; Lundahl, et al. 2013; Stecker, et al. 2012. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that combining evidence-based behavioral intervention and pharmacologic treatment was associated with better AUD treatment outcomes than clinical management or nonspecific counseling services Ray, et al. 2020.

MI, MET, CBT, and other approaches have been incorporated into many interventions for AUD treatment. Variables in studies of behavioral interventions for alcohol use make it difficult to compare and interpret the evidence and extrapolate it to “real-world” settings and individual patients. These variables include the type of approach, duration and number of sessions, type and training of the clinician delivering the intervention, treatment setting, mode of delivery (in-person or computerized), individual or group intervention, risk level of alcohol use or AUD, and concurrent pharmacologic treatment. Most clinical trials examining pharmacologic treatment include a psychological component (e.g., MI or CBT for all treatment groups).

MI is a way of helping patients recognize their current or potential problems and act toward resolving them, and it can be helpful for clinicians to understand and use an MI-informed approach when discussing alcohol use and AUD treatment plans with patients. The overall goal of MI is to increase the individual’s intrinsic motivation to facilitate change, and the method is particularly useful for those who are ambivalent about changing behavior or who are reluctant to change Miller and Rollnick 2002. This technique emphasizes patients’ autonomy while providing a safe space for collaboration and consistent engagement to enhance motivation for change. The MI approach also helps clinicians assess the patients’ readiness to change behavior and use that level as a starting point for counseling or treatment.

| Box 1: Key Principles of Motivational Interviewing |

|

MET, adapted from MI principles, is a manual-based intervention designed to help patients explore ambivalence about alcohol use and develop intrinsic motivation to reduce or abstain from alcohol use Lenz, et al. 2016. CBT, individually or in groups, focuses on how thoughts, feelings, and behaviors influence each other and can be particularly useful for helping patients recognize and manage individual triggers for alcohol use. For CBT in an online format, see Computer Based Training for Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT4CBT).

Other behavioral approaches include mindfulness and contingency management (CM). A mindfulness approach seeks to help individuals with SUDs, including AUD, monitor for and relate differently to internal and environmental cues that trigger substance use Bowen, et al. 2014. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention programs have been associated with significant improvements in some alcohol-related outcomes compared with other psychosocial interventions, but data are limited Grant, et al. 2017; Bowen, et al. 2014. CM aims to improve SUD treatment outcomes, such as engagement in care or abstinence, by providing patient incentives. In studies, contingency management has been associated with significant improvements in alcohol-related outcomes, but providing a CM intervention in a real-world medical setting has been difficult Getty, et al. 2019; Barnett, et al. 2017; McDonell, et al. 2017; Benishek, et al. 2014; Dougherty, et al. 2014; Prendergast, et al. 2006.

To date, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved a prescription CBT app for use as an adjunct treatment for alcohol and other substance use disorders Maricich, et al. 2022; FDA(a) 2017, but availability is uncertain. This mobile system includes a patient app and a clinician dashboard and is intended to be used in conjunction with outpatient therapy and a CM system. Mobile apps (SoberDiary) and low-cost breathalyzer devices can be purchased by individuals, and studies have shown combining mobile apps with remote breathalyzers that provide CM is an effective strategy for reducing alcohol use Oluwoye, et al. 2020; Koffarnus, et al. 2018; You, et al. 2017; Alessi and Petry 2013. As a new format for treatment, app-based CM has some promising results but has not yet been widely adopted into real-world settings.

Mutual-support programs: Self-Management and Recovery Training (SMART Recovery) focuses on self-empowerment and provides mutual support through in-person group meetings and online formats. The program uses rational emotive behavior therapy, a form of CBT, to facilitate changes in thinking and thus in emotions and behaviors Horvath and Yeterian 2012. Some studies have shown positive alcohol-related treatment outcomes, but the data are inconsistent Beck, et al. 2017. Some patients may benefit from Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), a 12-step mutual-support group approach based on fellowship and the role of a higher power. A recent systematic review identified high-quality evidence that AA and 12-step facilitation interventions were at least as effective in increasing abstinence and improving alcohol-related outcomes as clinical psychological interventions (e.g., MET, CBT, other 12‐step program variants) Kelly, et al. 2020. Mutual-support groups can complement pharmacologic and other treatment modalities.

| RESOURCES |

Motivational Interviewing

Medical Management Treatment Manual

Mutual-Support Programs |

Preferred Pharmacologic Treatment

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Preferred Pharmacologic Treatment

Acamprosate

Oral or Injectable Long-Acting Extended-Release Naltrexone

|

Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; CrCl, creatinine clearance; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; XR, extended-release. |

Based on strong clinical evidence, acamprosate and oral or XR naltrexone are the preferred pharmacologic treatments for individuals with moderate or severe AUD who have a goal of reducing or abstaining from alcohol use SAMHSA 2015; Jonas, et al. 2014. In individuals with mild AUD, clinicians may consider pharmacologic treatment with oral acamprosate or oral or XR naltrexone. Clinical trials directly comparing acamprosate and naltrexone and meta-analyses have not consistently established the superiority of one medication over the other in reducing heavy drinking Jonas, et al. 2014; Mann, et al. 2013; Anton, et al. 2006; Morley, et al. 2006; Kiefer, et al. 2003. There is minimal and mixed evidence on whether combining naltrexone and acamprosate has an additive effect on alcohol consumption outcomes Anton, et al. 2006; Kiefer, et al. 2003.

Acamprosate

Efficacy: Alcohol withdrawal produces a neurobiologic derangement in gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA), N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA), and glutamate transmission. Acamprosate modulates transmission from GABAA and NMDA receptors, which can restore neuronal balance and mitigate the associated symptoms Kalk and Lingford-Hughes 2014.

In clinical trials comparing acamprosate treatment with placebo, acamprosate increased the proportion of individuals who maintained complete abstinence from alcohol (complete abstinence rate), the mean cumulative abstinence duration, the percentage of alcohol-free days, and the median time to first drink Higuchi 2015; Plosker 2015; Gual and Lehert 2001; Tempesta, et al. 2000; Geerlings, et al. 1997; Pelc, et al. 1997; Poldrugo 1997; Sass, et al. 1996; Whitworth, et al. 1996; Paille, et al. 1995. A meta-analysis from 2014 found that acamprosate was significantly associated with a decreased return to any drinking and with a decreased percentage of drinking days throughout treatment Jonas, et al. 2014.

Who to treat: Acamprosate can be initiated if the individual is still actively using alcohol, but the efficacy of treatment during active alcohol use is unknown. Clinicians should initiate treatment with acamprosate as soon as the individual has abstained from alcohol use (within 7 days) for the best treatment response. Assessment of motivation will help identify candidates for acamprosate, which has been found to be most effective in patients with high levels of motivation Jonas, et al. 2014. Motivational interviewing (MI) may be used to enhance motivation.

Because acamprosate is excreted through the kidneys, clinicians should measure CrCl before starting treatment. Dose reduction may be necessary for patients with CrCl between 30 and 50 mL/min or eGFR between 30 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2. Acamprosate may be a good option for patients with AUD who have significant hepatic dysfunction because it is not metabolized through the liver and has no reported risk of hepatotoxicity.

Initial and maintenance dosage: Oral acamprosate is typically started and continued as 3 doses daily, two 333 mg tablets for each dose for a total of 1,998 mg daily (see Table 1, below). Acamprosate may be maintained if the individual continues or returns to alcohol use.

Adverse events: Acamprosate is generally well tolerated; the most frequently reported adverse effect in clinical trials was diarrhea Sinclair, et al. 2016; Chick, et al. 2000; Lhuintre, et al. 1985. If diarrhea is severe, a temporary dose reduction may be beneficial.

Naltrexone

Efficacy: Naltrexone is an opioid receptor antagonist used in the treatment of individuals with AUD or opioid use disorder (OUD). Alcohol use increases the activity of the endogenous opioid system. As an opioid receptor antagonist, naltrexone interferes with the rewarding aspects of alcohol Ray, et al. 2010; Pettinati, et al. 2006; Mason, et al. 2002. Naltrexone may also decrease subjective cravings for alcohol Maisel, et al. 2013.

Clinical trials have shown that naltrexone improves alcohol use outcomes and, specifically, decreases the likelihood of return to drinking and the overall number of drinking days Jonas, et al. 2014. A meta-analysis of studies evaluating treatment with oral naltrexone showed that oral naltrexone 50 mg daily was associated with decreased return to any drinking and decreased return to heavy drinking, and XR naltrexone was associated with reduced heavy drinking days Jonas, et al. 2014. An ongoing randomized controlled trial by Lee, et al., is examining the effectiveness of oral versus XR naltrexone in producing abstinence or moderate drinking Malone, et al. 2019. Studies have shown that naltrexone more effectively reduces alcohol consumption in individuals who use nicotine or cigarettes than those who do not Anton, et al. 2018; Fucito, et al. 2012, which may be one factor in selecting pharmacologic treatment.

Who to treat: Active alcohol use is not a contraindication to initiating or maintaining treatment with naltrexone (oral and XR formulations). For some patients, reduced alcohol use rather than abstinence may be a treatment goal. If alcohol use is significantly reduced abruptly, individuals should be monitored for alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

Naltrexone is a preferred AUD treatment option in patients with aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase levels within 3 to 5 times the upper limit of normal Kwo, et al. 2017; Turncliff, et al. 2005, but it should be prescribed with caution in patients with abnormal liver function FDA 2022; FDA 2013. With follow-up liver tests and symptom monitoring, naltrexone has been used safely and effectively in people with liver disease, including compensated cirrhosis Ayyala, et al. 2022. In patients with abnormal liver function, baseline assessment of liver function should be performed before treatment initiation, and the extent of liver abnormalities may guide continued testing or referral to an experienced liver specialist. Clinicians can consider performing follow-up liver function tests 4 to 12 weeks after initiating naltrexone treatment Lucey, et al. 2008.

Individuals with AUD should be abstinent from opioids for approximately 7 to 14 days before initiating XR naltrexone, which is also a U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved treatment for opioid use disorder (see NYSDOH AI guideline Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder > Naltrexone). Clinicians should confirm the length of time since last opioid use by performing a naloxone challenge. Administer intranasal naloxone as available (e.g., 4 mg/0.1 mL) and observe the reaction. In individuals with recent opioid use, this may precipitate opioid withdrawal. If a patient is already taking oral naltrexone, a naloxone challenge is not necessary.

Oral naltrexone: The recommended induction and maintenance doses of oral naltrexone is 50 mg daily. However, a dose of 100 mg daily was used and well tolerated in the large COMBINE trial Anton, et al. 2018, so a dose increase may be considered. Some clinicians advise patients to initiate naltrexone with a dose of 25 mg on day 1 and increase the dose to 50 mg on day 2. In clinical studies, high adherence to oral naltrexone, defined as pills taken on more than 80% to 90% of days, was necessary to achieve significant treatment effects Srisurapanont and Jarusuraisin 2005; Chick, et al. 2000. Because of oral naltrexone’s short half-life, the timing of the daily dose should be considered. Advise patients taking oral naltrexone to monitor alcohol cravings and medication effectiveness throughout the day and adjust the timing of the naltrexone dose accordingly. For example, if a patient tends to experience cravings or use alcohol at night, taking naltrexone in the evening may be more effective than in the morning. Assessing and supporting a patient’s ability to adhere to oral naltrexone before starting treatment (e.g., via MI) is essential. Engaging family members or others to assist with adherence to oral naltrexone can be helpful. XR naltrexone may improve adherence compared with oral naltrexone Hartung, et al. 2014.

Injectable XR naltrexone: Before initiating treatment with injectable XR naltrexone, clinicians should prescribe an oral trial of naltrexone (50 mg once daily for at least 3 days) to ensure patients tolerate the medication. XR naltrexone is administered as a 380 mg intramuscular gluteal injection every 28 days (alternating buttocks for each subsequent injection). When an XR naltrexone injection is delayed beyond 28 days, clinicians can provide patients with a prescription for daily oral naltrexone (50 mg daily) to take until they can receive the injection.

Adverse events: Oral and XR naltrexone are generally well tolerated. The more common adverse events include gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea) and dizziness FDA 2022; FDA 2013. Gastrointestinal adverse events associated with naltrexone may be more common among women than men Herbeck, et al. 2016. If an individual experiences adverse events with oral naltrexone, clinicians can consider a reduced dose of 25 mg Anton 2008. XR naltrexone can cause pain or hardening of soft tissue at the injection site. The potential for bleeding at the injection site in individuals who have coagulopathy or are taking anticoagulants should be considered. Sufficient adipose tissue is required for injection, which may be difficult in an individual with cachexia.

| Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; CrCl, creatinine clearance; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; XR, extended-release.

Notes:

|

||

| Table 1: Preferred Pharmacologic Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder in Nonpregnant Adults [a] | ||

| Medication [b] | Dosage | Considerations |

| Acamprosate oral (Campral) |

Initial and maintenance: 666 mg 3 times per day |

|

| Naltrexone oral (Revia) |

Initial and maintenance: 50 mg once daily

|

|

| XR Naltrexone, long-acting injectable (Vivitrol) |

Initial: 50 mg oral naltrexone once daily for at least 3 days

Maintenance: 380 mg intragluteal injection every 28 days |

|

Alternative Pharmacologic Treatment

| RECOMMENDATIONS |

Alternative Pharmacologic Treatment

Disulfiram

Gabapentin or Topiramate

|

Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase. |

For individuals with AUD who have not responded to or are intolerant of naltrexone or acamprosate, or who prefer a different medication, alternative treatment options include disulfiram, gabapentin, and topiramate (see Table 2, below). Of the 3 medications, only disulfiram is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for AUD treatment. Other alternative treatments for AUD, including baclofen and varenicline, have been investigated, but the evidence of their efficacy is mixed Agabio, et al. 2023; Bahji, et al. 2022; Fischler, et al. 2022. Further studies are needed to confirm the benefits of these treatments for AUD.

Disulfiram

Efficacy: Concomitant use of alcohol and disulfiram can produce a severe physiologic response (the disulfiram-ethanol reaction) that may result in low blood pressure, tachycardia, facial flushing, nausea, vomiting, dyspnea, sweating, dizziness, blurred vision, and confusion Bell and Smith 1949. The psychological threat of the unpleasant physiologic effects is believed to be the primary mechanism for dissuading alcohol use in individuals with AUD Skinner, et al. 2014.

Evidence is mixed on the effectiveness of disulfiram for the treatment of AUD. Well-controlled clinical trials do not support an association between disulfiram use and reduction in alcohol consumption Jonas, et al. 2014. However, it may be difficult to evaluate disulfiram in a double-blind study design because the threat of the physiologic effects of combining alcohol and disulfiram, which is present for both treatment and control groups, is directly related to the efficacy of the drug Skinner, et al. 2014. A meta-analysis showed that disulfiram effectively improved consumption outcomes in open-label trials (no blinding for participants or researchers) but not in blinded randomized controlled trials Skinner, et al. 2014.

Since the 1970s, studies examining the effectiveness of disulfiram have typically compared unsupervised administration of disulfiram with administration supervised by health professionals or by suitable delegated associates of the participant. Results suggest that disulfiram can be an effective treatment with supervised administration, but adherence is low with unsupervised administration Brewer, et al. 2017; Skinner, et al. 2014; Jørgensen, et al. 2011; Fuller, et al. 1986.

Who to treat: Disulfiram is an alternative treatment option for individuals who have a clear goal of alcohol abstinence and are able to abstain for at least 12 hours before initiating treatment. Clinicians should advise patients that adverse effects may occur with alcohol consumption for up to 14 days after taking disulfiram.

Before initiating treatment with disulfiram, clinicians should perform baseline liver function testing, including AST/ALT tests, and consider disulfiram as an option only if AST/ALT levels are within 3 to 5 times the upper limit of normal Kwo, et al. 2017. Disulfiram has been associated with mild increases in hepatic enzymes in approximately 25% of individuals taking the medication Björnsson, et al. 2006. Acute and potentially fatal hepatotoxicity is very rare (1 per 10,000 to 30,000 years of disulfiram treatment) Björnsson, et al. 2006. It may be useful for clinicians to obtain follow-up liver test results within 1 month of initiating treatment. The extent of liver abnormalities should guide continued testing or referral to a liver specialist. In addition, disulfiram is not considered safe in individuals with serious medical comorbidities (e.g., cardiovascular disease) or serious mental illnesses (e.g., psychotic disorders) FDA 2015.

Induction and maintenance dosage: The initial dose of disulfiram is 250 mg to 500 mg once daily for 1 to 2 weeks FDA 2015. After the initiation phase, the recommended maintenance dose of disulfiram is 125 mg to 500 mg once daily based on response and tolerability. Typically, the maintenance dose is 250 mg once daily; the maximum dose is 500 mg once daily (see Table 2, below).

Disulfiram does not reduce an individual’s alcohol cravings. Motivation and consistent adherence are required for disulfiram to be an effective deterrent to alcohol use. In clinical trials, individuals who chose disulfiram as their preferred treatment and were highly adherent or were receiving disulfiram under supervision achieved the greatest success Johnson 2008; Laaksonen, et al. 2008; O'Farrell, et al. 1995; Chick, et al. 1992.

| Box 2: Patient Education Points on Disulfiram |

|

Adverse events: Consuming alcohol while taking disulfiram can result in the adverse reactions described above. Because disulfiram is contraindicated in individuals with severe myocardial disease or coronary occlusion, it may be appropriate to assess cardiac function before starting treatment with disulfiram. Disulfiram is not recommended for patients with seizure disorders or a history of psychosis. Caution should be taken in prescribing disulfiram to patients who have a family history of psychosis FDA 2015.

Gabapentin

Efficacy: Gabapentin’s mechanism of action in treating AUD is not fully understood, but evidence suggests that it modulates and stabilizes central stress systems dysregulated by alcohol use cessation Roberto, et al. 2010; Roberto, et al. 2008. Although gabapentin is not approved by the FDA for AUD treatment, its use has been associated with reductions in alcohol consumption and craving Mason, et al. 2018; Mason, et al. 2014. As an adjunct to benzodiazepines, gabapentin is effective in treating common symptoms of acute and protracted alcohol withdrawal, including anxiety and sleep disturbances Mason, et al. 2018; Rosenberg, et al. 2014; Lavigne, et al. 2012; Myrick, et al. 2009; Brower, et al. 2008; Bazil, et al. 2005; Karam-Hage and Brower 2000. Gabapentin may be used to prevent alcohol withdrawal when indicated, e.g., for a hospitalized patient being treated for a condition not related to alcohol withdrawal Maldonado 2017.

| Box 3: Gabapentin Misuse |

|

Who to treat: At doses of up to 1,800 mg daily, gabapentin is safe and well tolerated in individuals with AUD Mason, et al. 2018; Mason, et al. 2014. No adverse effects have been reported with concomitant use of gabapentin and alcohol, so alcohol abstinence is not required for gabapentin initiation Myrick, et al. 2007. Gabapentin is excreted through the kidneys; clinicians may consider testing for serum creatinine levels, particularly when administering high doses of gabapentin. Dose reduction may be necessary for patients with reduced renal function. Because gabapentin is not metabolized through the liver and has no reported risk of hepatotoxicity, it may be a good option for individuals with AUD who have significant hepatic dysfunction.

Induction and maintenance dosage: The initial dose of gabapentin is 300 mg once daily, with increases in increments of 300 mg every 1 to 2 days based on improvement in symptoms and tolerability. The maintenance dose is individualized and generally divided into 3 doses per day. Based on studies of gabapentin for the treatment of other conditions (e.g., epilepsy, postherpetic neuralgia), up to 2,400 mg or 3,600 mg per day, divided into 3 doses, can be considered for maintenance FDA(b) 2017.

Adverse effects: Common adverse effects include headache, insomnia, fatigue, muscle aches, and gastrointestinal complaints. In clinical trials, these effects were mild or moderate, did not result in drug discontinuation, and were not significantly different from adverse effects reported with placebo treatment Mason, et al. 2018.

Topiramate

Efficacy: Topiramate’s mechanism of action in treating AUD is not fully understood, but evidence suggests that it enhances GABAergic neurotransmission and suppresses glutamatergic neurotransmission, helping to normalize and restore balance in the reward circuits of the brain Cheng, et al. 2018; Frye, et al. 2016; Shank and Maryanoff 2008.

Like gabapentin, topiramate is not approved by the FDA for AUD treatment, but it has been associated with fewer drinking days, fewer drinks per drinking day, a decreased percentage of heavy drinking days, and an increased number of abstinent days Manhapra, et al. 2019. To a lesser degree, topiramate has been associated with reduced cravings for alcohol Manhapra, et al. 2019. The effectiveness of topiramate for AUD does not appear to be substantially affected by preinitiation alcohol abstinence or detoxification Maisel, et al. 2013.

Who to treat: Clinicians can offer topiramate as an alternative therapy to patients with moderate or severe AUD (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 criteria) who have a goal of reducing alcohol use or achieving abstinence. Abstinence from alcohol is not a requirement for initiating or maintaining treatment.

Induction and maintenance dosage: The initial dose of topiramate is 25 mg once daily, with increases in increments of 50 mg once every 7 days. The maintenance dose ranges from 200 mg to 400 mg daily, divided into 2 doses Knapp, et al. 2015; Kranzler, et al. 2014; Johnson, et al. 2003. In patients with moderate-to-severe renal impairment, a 50% dose reduction is advised Guerrini and Parmeggiani 2006; Perucca 1997.

Adverse effects: Adverse effects that occurred in more than 10% of study subjects include paresthesia Swietach, et al. 2003; Spitzer, et al. 2002; Fujii, et al. 1993 and cognitive impairment Gomer, et al. 2007. These effects were mostly observed in the dose titration phase and often resolved with continued treatment. Rare adverse effects include increased rate of renal calculi (2- to 4-fold) Welch, et al. 2006, oligohidrosis Ma, et al. 2007; Cerminara, et al. 2006, acute visual disturbances, and myopia and acute angle-closure glaucoma Shank and Maryanoff 2008.

| Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; AUD, alcohol use disorder; CrCl, creatinine clearance; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Notes:

|

||

| Table 2: Alternative Pharmacologic Treatment of Alcohol Use Disorder in Nonpregnant Adults [a] | ||

| Medication [b] | Dosage | Considerations |

| Disulfiram oral (multiple brands) |

Initial and maintenance: 500 mg once daily for 1 to 2 weeks. Reduce to 250 mg once daily. |

|

| Gabapentin oral (multiple brands) |

Initial: 300 mg once daily

Titrate: Increase in increments of 300 mg. Maintenance: Up to 3,600 mg daily, divided into 3 doses; dose is based on response and tolerance. |

|

| Topiramate oral (multiple brands) |

Initial: 25 mg once daily

Titrate: Increase dose by 50 mg increments each week to a maximum of 400 mg daily administered in 2 divided doses. Maintenance: 200 to 400 mg daily divided into 2 doses |

|

All Recommendations

| ALL RECOMMENDATIONS: TREATMENT OF ALCOHOL USE DISORDER |

Who to Treat

Treatment Goals and Selection

Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome

Follow-Up

Behavioral Treatment

Preferred Pharmacologic Treatment

Acamprosate

Oral or Injectable Long-Acting Extended-Release Naltrexone

Alternative Pharmacologic Treatment

Disulfiram

Gabapentin or Topiramate

|

Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CrCl, creatinine clearance; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; SUD, substance use disorder; XR, extended-release. Notes:

|

Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

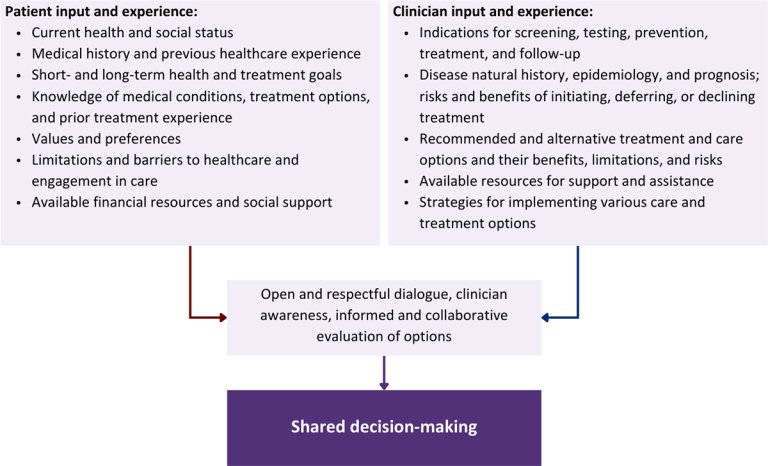

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

References

Agabio R., Saulle R., Rösner S., et al. Baclofen for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2023;1(1):CD012557. [PMID: 36637087]

Alessi S. M., Petry N. M. A randomized study of cellphone technology to reinforce alcohol abstinence in the natural environment. Addiction 2013;108(5):900-909. [PMID: 23279560]

Anton R. F. Naltrexone for the management of alcohol dependence. N Engl J Med 2008;359(7):715-21. [PMID: 18703474]

Anton R. F., Latham P., Voronin K., et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180(5):728-36. [PMID: 32150232]

Anton R. F., Latham P. K., Voronin K. E., et al. Nicotine-use/smoking is associated with the efficacy of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2018;42(4):751-60. [PMID: 29431852]

Anton R. F., O'Malley S. S., Ciraulo D. A., et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2006;295(17):2003-17. [PMID: 16670409]

APA. Practice guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder. 2017 Nov. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/pdf/10.1176/appi.books.9781615371969 [accessed 2020 May 6]

Ayyala D., Bottyan T., Tien C., et al. Naltrexone for alcohol use disorder: hepatic safety in patients with and without liver disease. Hepatol Commun 2022;6(12):3433-42. [PMID: 36281979]

Baan R., Straif K., Grosse Y., et al. Carcinogenicity of alcoholic beverages. Lancet Oncol 2007;8(4):292-93. [PMID: 17431955]

Bagnardi V., Rota M., Botteri E., et al. Alcohol consumption and site-specific cancer risk: a comprehensive dose-response meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2015;112(3):580-93. [PMID: 25422909]

Bahji A., Bach P., Danilewitz M., et al. Pharmacotherapies for adults with alcohol use disorders: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Addict Med 2022;16(6):630-38. [PMID: 35653782]

Barnett N. P., Celio M. A., Tidey J. W., et al. A preliminary randomized controlled trial of contingency management for alcohol use reduction using a transdermal alcohol sensor. Addiction 2017;112(6):1025-35. [PMID: 28107772]

Barrons R., Roberts N. The role of carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine in alcohol withdrawal syndrome. J Clin Pharm Ther 2010;35(2):153-67. [PMID: 20456734]

Bazil C. W., Battista J., Basner R. C. Gabapentin improves sleep in the presence of alcohol. J Clin Sleep Med 2005;1(3):284-87. [PMID: 17566190]

Beck A. K., Forbes E., Baker A. L., et al. Systematic review of SMART Recovery: outcomes, process variables, and implications for research. Psychol Addict Behav 2017;31(1):1-20. [PMID: 28165272]

Bell R. G., Smith H. W. Preliminary report on clinical trials of antabuse. Can Med Assoc J 1949;60(3):286-88. [PMID: 18110807]

Benishek L. A., Dugosh K. L., Kirby K. C., et al. Prize-based contingency management for the treatment of substance abusers: a meta-analysis. Addiction 2014;109(9):1426-36. [PMID: 24750232]

Björnsson E., Nordlinder H., Olsson R. Clinical characteristics and prognostic markers in disulfiram-induced liver injury. J Hepatol 2006;44(4):791-97. [PMID: 16487618]

Blondell R. D. Ambulatory detoxification of patients with alcohol dependence. Am Fam Physician 2005;71(3):495-502. [PMID: 15712624]

Bogenschutz M. P., Ross S., Bhatt S., et al. Percentage of heavy drinking days following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy vs placebo in the treatment of adult patients with alcohol use disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2022;79(10):953-62. [PMID: 36001306]

Bonnet U., Banger M., Leweke F. M., et al. Treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome with gabapentin. Pharmacopsychiatry 1999;32(3):107-9. [PMID: 10463378]

Bowen S., Witkiewitz K., Clifasefi S. L., et al. Relative efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention, standard relapse prevention, and treatment as usual for substance use disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71(5):547-56. [PMID: 24647726]

Brewer C., Streel E., Skinner M. Supervised disulfiram's superior effectiveness in alcoholism treatment: ethical, methodological, and psychological aspects. Alcohol Alcohol 2017;52(2):213-19. [PMID: 28064151]

Brower K. J., Myra Kim H., Strobbe S., et al. A randomized double-blind pilot trial of gabapentin versus placebo to treat alcohol dependence and comorbid insomnia. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2008;32(8):1429-38. [PMID: 18540923]

Calleja-Conde J., Morales-García J. A., Echeverry-Alzate V., et al. Classic psychedelics and alcohol use disorders: a systematic review of human and animal studies. Addict Biol 2022;27(6):e13229. [PMID: 36301215]

Cerminara C., Seri S., Bombardieri R., et al. Hypohidrosis during topiramate treatment: a rare and reversible side effect. Pediatr Neurol 2006;34(5):392-94. [PMID: 16648001]

Cheng H., Kellar D., Lake A., et al. Effects of alcohol cues on MRS glutamate levels in the anterior cingulate. Alcohol Alcohol 2018;53(3):209-15. [PMID: 29329417]

Cherpitel C. J. Alcohol and injuries: a review of international emergency room studies since 1995. Drug Alcohol Rev 2007;26(2):201-14. [PMID: 17364856]

Chick J., Anton R., Checinski K., et al. A multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence or abuse. Alcohol Alcohol 2000;35(6):587-93. [PMID: 11093966]

Chick J., Gough K., Falkowski W., et al. Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism. Br J Psychiatry 1992;161:84-89. [PMID: 1638335]

DiClemente C. C., Corno C. M., Graydon M. M., et al. Motivational interviewing, enhancement, and brief interventions over the last decade: a review of reviews of efficacy and effectiveness. Psychol Addict Behav 2017;31(8):862-87. [PMID: 29199843]

Dougherty D. M., Hill-Kapturczak N., Liang Y., et al. Use of continuous transdermal alcohol monitoring during a contingency management procedure to reduce excessive alcohol use. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;142:301-6. [PMID: 25064019]

Driscoll T. R., Harrison J. A., Steenkamp M. Review of the role of alcohol in drowning associated with recreational aquatic activity. Inj Prev 2004;10(2):107-13. [PMID: 15066977]

Elholm B., Larsen K., Hornnes N., et al. A psychometric validation of the Short Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (SAWS). Alcohol Alcohol 2010;45(4):361-65. [PMID: 20570824]

FDA. Revia (naltrexone hydrochloride tablets USP). 2013 Oct. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/018932s017lbl.pdf [accessed 2023 Jul 18]

FDA. Antabuse (disulfiram tablets USP). 2015 Sep. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=f0ca0e1f-9641-48d5-9367-e5d1069e8680 [accessed 2023 Jul 18]

FDA. Vivitrol (naltrexone for extended-release injectable suspension), for intramuscular use. 2022 Sep. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2022/021897s057lbl.pdf [accessed 2023 Jul 24]

FDA(a). FDA permits marketing of mobile medical application for substance use disorder. 2017 Sep 14. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-permits-marketing-mobile-medical-application-substance-use-disorder [accessed 2023 Jul 18]

FDA(b). Neurontin (gabapentin) capsules, for oral use; tablets, for oral use; oral suspension. 2017 Oct. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/020235s064_020882s047_021129s046lbl.pdf [accessed 2023 Jul 18]

Fischler P. V., Soyka M., Seifritz E., et al. Off-label and investigational drugs in the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a critical review. Front Pharmacol 2022;13:927703. [PMID: 36263121]

Fluyau D., Kailasam V. K., Pierre C. G. Beyond benzodiazepines: a meta-analysis and narrative synthesis of the efficacy and safety of alternative options for alcohol withdrawal syndrome management. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2023;79(9):1147-57. [PMID: 37380897]

Frye M. A., Hinton D. J., Karpyak V. M., et al. Anterior cingulate glutamate is reduced by acamprosate treatment in patients with alcohol dependence. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2016;36(6):669-74. [PMID: 27755217]

Fucito L. M., Park A., Gulliver S. B., et al. Cigarette smoking predicts differential benefit from naltrexone for alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry 2012;72(10):832-38. [PMID: 22541040]

Fujii H., Nakamura K., Takeo K., et al. Heterogeneity of carbonic anhydrase and 68 kDa neurofilament in nerve roots analyzed by two-dimensional electrophoresis. Electrophoresis 1993;14(10):1074-78. [PMID: 8125058]

Fuller R. K., Branchey L., Brightwell D. R., et al. Disulfiram treatment of alcoholism. A Veterans Administration cooperative study. JAMA 1986;256(11):1449-55. [PMID: 3528541]

Garel N., McAnulty C., Greenway K. T., et al. Efficacy of ketamine intervention to decrease alcohol use, cravings, and withdrawal symptoms in adults with problematic alcohol use or alcohol use disorder: a systematic review and comprehensive analysis of mechanism of actions. Drug Alcohol Depend 2022;239:109606. [PMID: 36087563]

Geerlings P. J., Ansoms C., van den Brink W. Acamprosate and prevention of relapse in alcoholics. Eur Addiction Res 1997;3(3):129-37. https://doi.org/10.1159/000259166

Getty C. A., Morande A., Lynskey M., et al. Mobile telephone-delivered contingency management interventions promoting behaviour change in individuals with substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction 2019;114(11):1915-25. [PMID: 31265747]

Gomer B., Wagner K., Frings L., et al. The influence of antiepileptic drugs on cognition: a comparison of levetiracetam with topiramate. Epilepsy Behav 2007;10(3):486-94. [PMID: 17409025]

Gossop M., Keaney F., Stewart D., et al. A Short Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (SAWS): development and psychometric properties. Addict Biol 2002;7(1):37-43. [PMID: 11900621]

Grabski M., McAndrew A., Lawn W., et al. Adjunctive ketamine with relapse prevention-based psychological therapy in the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2022;179(2):152-62. [PMID: 35012326]

Grant S., Colaiaco B., Motala A., et al. Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance use disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Addict Med 2017;11(5):386-96. [PMID: 28727663]

Grewal P., Viswanathen V. A. Liver cancer and alcohol. Clin Liver Dis 2012;16(4):839-50. [PMID: 23101985]

Gual A., Lehert P. Acamprosate during and after acute alcohol withdrawal: a double-blind placebo-controlled study in Spain. Alcohol Alcohol 2001;36(5):413-18. [PMID: 11524307]

Guerrini R., Parmeggiani L. Topiramate and its clinical applications in epilepsy. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2006;7(6):811-23. [PMID: 16556095]

Hartung D. M., McCarty D., Fu R., et al. Extended-release naltrexone for alcohol and opioid dependence: a meta-analysis of healthcare utilization studies. J Subst Abuse Treat 2014;47(2):113-21. [PMID: 24854219]

Herbeck D. M., Jeter K. E., Cousins S. J., et al. Gender differences in treatment and clinical characteristics among patients receiving extended release naltrexone. J Addict Dis 2016;35(4):305-14. [PMID: 27192330]

Higuchi S. Efficacy of acamprosate for the treatment of alcohol dependence long after recovery from withdrawal syndrome: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in Japan (Sunrise Study). J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76(2):181-88. [PMID: 25742205]

Horvath A. T., Yeterian J. SMART recovery: self-empowering, science-based addiction recovery support. J Groups Addiction Recovery 2012;7(2-4):102-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/1556035X.2012.705651

Johnson B. A. Update on neuropharmacological treatments for alcoholism: scientific basis and clinical findings. Biochem Pharmacol 2008;75(1):34-56. [PMID: 17880925]

Johnson B. A., Ait-Daoud N., Bowden C. L., et al. Oral topiramate for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2003;361(9370):1677-85. [PMID: 12767733]

Jonas D. E., Amick H. R., Feltner C., et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2014;311(18):1889-1900. [PMID: 24825644]

Jørgensen C. H., Pedersen B., Tønnesen H. The efficacy of disulfiram for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2011;35(10):1749-58. [PMID: 21615426]

Kalk N. J., Lingford-Hughes A. R. The clinical pharmacology of acamprosate. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;77(2):315-23. [PMID: 23278595]

Karam-Hage M., Brower K. J. Gabapentin treatment for insomnia associated with alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157(1):151. [PMID: 10618048]

Kelly J. F., Humphreys K., Ferri M. Alcoholics Anonymous and other 12-step programs for alcohol use disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;3(3):CD012880. [PMID: 32159228]

Kiefer F., Jahn H., Tarnaske T., et al. Comparing and combining naltrexone and acamprosate in relapse prevention of alcoholism: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60(1):92-99. [PMID: 12511176]

Knapp C. M., Ciraulo D. A., Sarid-Segal O., et al. Zonisamide, topiramate, and levetiracetam: efficacy and neuropsychological effects in alcohol use disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2015;35(1):34-42. [PMID: 25427171]

Koffarnus M. N., Bickel W. K., Kablinger A. S. Remote alcohol monitoring to facilitate incentive-based treatment for alcohol use disorder: a randomized trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2018;42(12):2423-31. [PMID: 30335205]

Kranzler H. R., Covault J., Feinn R., et al. Topiramate treatment for heavy drinkers: moderation by a GRIK1 polymorphism. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171(4):445-52. [PMID: 24525690]

Kuehn B. M. Growing role of gabapentin in opioid-related overdoses highlights misuse potential and off-label prescribing practices. JAMA 2022;328(13):1283-85. [PMID: 36069924]

Kwo P. Y., Cohen S. M., Lim J. K. ACG clinical guideline: evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112(1):18-35. [PMID: 27995906]

Laaksonen E., Koski-Jännes A., Salaspuro M., et al. A randomized, multicentre, open-label, comparative trial of disulfiram, naltrexone and acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence. Alcohol Alcohol 2008;43(1):53-61. [PMID: 17965444]

Larsen A. R., Cummings J. R., von Esenwein S. A., et al. Trends in alcohol use disorder treatment utilization and setting from 2008 to 2017. Psychiatr Serv 2022;73(9):991-98. [PMID: 35193376]

Lavigne J. E., Heckler C., Mathews J. L., et al. A randomized, controlled, double-blinded clinical trial of gabapentin 300 versus 900 mg versus placebo for anxiety symptoms in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;136(2):479-86. [PMID: 23053645]

Lenz A. S., Rosenbaum L., Sheperis D. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of motivational enhancement therapy for reducing substance use. J Addiction Offender Couns 2016;37(2):66-86. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaoc.12017

Lhuintre J. P., Daoust M., Moore N. D., et al. Ability of calcium bis acetyl homotaurine, a GABA agonist, to prevent relapse in weaned alcoholics. Lancet 1985;1(8436):1014-16. [PMID: 2859465]

Lucey M. R., Silverman B. L., Illeperuma A., et al. Hepatic safety of once-monthly injectable extended-release naltrexone administered to actively drinking alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2008;32(3):498-504. [PMID: 18241321]

Lundahl B., Kunz C., Brownell C., et al. A meta-analysis of motivational interviewing: twenty-five years of empirical studies. Res Soc Work Pract 2010;20(2):137-60. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509347850

Lundahl B., Moleni T., Burke B. L., et al. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns 2013;93(2):157-68. [PMID: 24001658]

Ma L., Huang Y. G., Deng Y. C., et al. Topiramate reduced sweat secretion and aquaporin-5 expression in sweat glands of mice. Life Sci 2007;80(26):2461-68. [PMID: 17521680]

Magill M., Ray L., Kiluk B., et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioral therapy for alcohol or other drug use disorders: treatment efficacy by contrast condition. J Consult Clin Psychol 2019;87(12):1093-1105. [PMID: 31599606]

Magill M., Ray L. A. Cognitive-behavioral treatment with adult alcohol and illicit drug users: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2009;70(4):516-27. [PMID: 19515291]

Maisel N. C., Blodgett J. C., Wilbourne P. L., et al. Meta-analysis of naltrexone and acamprosate for treating alcohol use disorders: when are these medications most helpful?. Addiction 2013;108(2):275-93. [PMID: 23075288]

Maldonado J. R. Novel algorithms for the prophylaxis and management of alcohol withdrawal syndromes-beyond benzodiazepines. Crit Care Clin 2017;33(3):559-99. [PMID: 28601135]

Maldonado J. R., Sher Y., Das S., et al. Prospective validation study of the Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS) in medically ill inpatients: a new scale for the prediction of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Alcohol Alcohol 2015;50(5):509-18. [PMID: 25999438]

Malone M., McDonald R., Vittitow A., et al. Extended-release vs. oral naltrexone for alcohol dependence treatment in primary care (XON). Contemp Clin Trials 2019;81:102-9. [PMID: 30986535]

Manhapra A., Chakraborty A., Arias A. J. Topiramate pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder and other addictions: a narrative review. J Addict Med 2019;13(1):7-22. [PMID: 30096077]

Mann K., Lemenager T., Hoffmann S., et al. Results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled pharmacotherapy trial in alcoholism conducted in Germany and comparison with the US COMBINE study. Addict Biol 2013;18(6):937-46. [PMID: 23231446]

Maricich Y. A., Nunes E. V., Campbell A. N. C., et al. Safety and efficacy of a digital therapeutic for substance use disorder: secondary analysis of data from a NIDA clinical trials network study. Subst Abus 2022;43(1):937-42. [PMID: 35420979]

Mason B. J., Goodman A. M., Dixon R. M., et al. A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic drug interaction study of acamprosate and naltrexone. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002;27(4):596-606. [PMID: 12377396]

Mason B. J., Quello S., Goodell V., et al. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174(1):70-77. [PMID: 24190578]

Mason B. J., Quello S., Shadan F. Gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2018;27(1):113-24. [PMID: 29241365]

Mattson C. L., Chowdhury F., Gilson T. P. Notes from the field: trends in gabapentin detection and involvement in drug overdose deaths - 23 states and the District of Columbia, 2019-2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022;71(19):664-666. [PMID: 35552367]

Mayo-Smith M. F. Pharmacological management of alcohol withdrawal. A meta-analysis and evidence-based practice guideline. American Society of Addiction Medicine Working Group on Pharmacological Management of Alcohol Withdrawal. JAMA 1997;278(2):144-51. [PMID: 9214531]

McDonell M. G., Leickly E., McPherson S., et al. A randomized controlled trial of ethyl glucuronide-based contingency management for outpatients with co-occurring alcohol use disorders and serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatry 2017;174(4):370-77. [PMID: 28135843]

Mersfelder T. L., Nichols W. H. Gabapentin: abuse, dependence, and withdrawal. Ann Pharmacother 2016;50(3):229-33. [PMID: 26721643]

Miller S. The ASAM principles of addiction medicine; 2018. https://shop.lww.com/The-ASAM-Principles-of-Addiction-Medicine/p/9781496370983

Miller W., Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing, preparing people to change addictive behavior; 2002. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Motivational_Interviewing_Second_Edition/p7TpwAEACAAJ

Morley K. C., Teesson M., Reid S. C., et al. Naltrexone versus acamprosate in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a multi-centre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Addiction 2006;101(10):1451-62. [PMID: 16968347]

Muncie H. L., Yasinian Y., Oge L. Outpatient management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Am Fam Physician 2013;88(9):589-95. [PMID: 24364635]

Myrick H., Anton R., Voronin K., et al. A double-blind evaluation of gabapentin on alcohol effects and drinking in a clinical laboratory paradigm. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2007;31(2):221-27. [PMID: 17250613]

Myrick H., Anton R. F. Treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Health Res World 1998;22(1):38-43. [PMID: 15706731]

Myrick H., Malcolm R., Randall P. K., et al. A double-blind trial of gabapentin versus lorazepam in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2009;33(9):1582-88. [PMID: 19485969]

Nadkarni A., Massazza A., Guda R., et al. Common strategies in empirically supported psychological interventions for alcohol use disorders: a meta-review. Drug Alcohol Rev 2023;42(1):94-104. [PMID: 36134481]

NIAAA(a). Alcohol's effects on health: research-based information on drinking and its impact. 2023. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohols-effects-health/alcohol-topics/alcohol-facts-and-statistics/alcohol-and-human-body [accessed 2023 May 18]

NIAAA(b). NIAAA recovery research definitions. 2023. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/research/niaaa-recovery-from-alcohol-use-disorder/definitions [accessed 2023 Sep 19]

O'Farrell T. J., Allen J. P., Litten R. Z. Disulfiram (antabuse) contracts in treatment of alcoholism. NIDA Res Monogr 1995;150:65-91. [PMID: 8742773]

Oluwoye O., Reneau H., Herron J., et al. Pilot study of an integrated smartphone and breathalyzer contingency management intervention for alcohol use. J Addict Med 2020;14(3):193-98. [PMID: 31567597]

Paille F. M., Guelfi J. D., Perkins A. C., et al. Double-blind randomized multicentre trial of acamprosate in maintaining abstinence from alcohol. Alcohol Alcohol 1995;30(2):239-47. [PMID: 7662044]

Pelc I., Verbanck P., Le Bon O., et al. Efficacy and safety of acamprosate in the treatment of detoxified alcohol-dependent patients. A 90-day placebo-controlled dose-finding study. Br J Psychiatry 1997;171:73-77. [PMID: 9328500]

Perucca E. A pharmacological and clinical review on topiramate, a new antiepileptic drug. Pharmacol Res 1997;35(4):241-56. [PMID: 9264038]

Pettinati H. M., O'Brien C. P., Rabinowitz A. R., et al. The status of naltrexone in the treatment of alcohol dependence: specific effects on heavy drinking. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2006;26(6):610-25. [PMID: 17110818]

Plosker G. L. Acamprosate: a review of its use in alcohol dependence. Drugs 2015;75(11):1255-68. [PMID: 26084940]

Poldrugo F. Acamprosate treatment in a long-term community-based alcohol rehabilitation programme. Addiction 1997;92(11):1537-46. [PMID: 9519495]

Prendergast M., Podus D., Finney J., et al. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction 2006;101(11):1546-60. [PMID: 17034434]

Ray L. A., Chin P. F., Miotto K. Naltrexone for the treatment of alcoholism: clinical findings, mechanisms of action, and pharmacogenetics. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 2010;9(1):13-22. [PMID: 20201811]

Ray L. A., Meredith L. R., Kiluk B. D., et al. Combined pharmacotherapy and cognitive behavioral therapy for adults with alcohol or substance use disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(6):e208279. [PMID: 32558914]

Roberto M., Cruz M. T., Gilpin N. W., et al. Corticotropin releasing factor-induced amygdala gamma-aminobutyric acid release plays a key role in alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry 2010;67(9):831-39. [PMID: 20060104]

Roberto M., Gilpin N. W., O'Dell L. E., et al. Cellular and behavioral interactions of gabapentin with alcohol dependence. J Neurosci 2008;28(22):5762-71. [PMID: 18509038]

Rosenberg R. P., Hull S. G., Lankford D. A., et al. A randomized, double-blind, single-dose, placebo-controlled, multicenter, polysomnographic study of gabapentin in transient insomnia induced by sleep phase advance. J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10(10):1093-1100. [PMID: 25317090]