Viremic -- Cases in HIV Podcast

Join hosts Eileen Scully, MD, and Christopher Hoffmann, MD, HIV specialists at Johns Hopkins University, for this biweekly podcast featuring case discussions that explore quandaries in adult HIV care. Each case discussion includes medical history and diagnoses, challenges in care and treatment, and key evidence and guidelines that informed clinical decision-making.

Join hosts Eileen Scully, MD, and Christopher Hoffmann, MD, HIV specialists at Johns Hopkins University, for this biweekly podcast featuring case discussions that explore quandaries in adult HIV care. Each case discussion includes medical history and diagnoses, challenges in care and treatment, and key evidence and guidelines that informed clinical decision-making.

All Cases (episodes)

- Case 14. “AIDS Is Not My Worst Problem”: Caring for Women with HIV (1/20/26)

- Case 13. Got PrEP? HIV Adjacent Care (1/6/26)

- Holiday Greetings (12/23/25)

- Case 12. Injectable ART Failure: Minor Risk of a Major Event (12/9/25)

- Case 11. Unfolding Stories to Untangle Syphilis Testing (11/25/25)

- Case 10. A Growing Problem: ART-Associated Weight Gain (11/11/25)

- Case 9. A New TRIO to Reduce ART Complexity (10/28/25)

- Case 8. Charting a Path Forward (10/14/25)

- Case 7. Newer Kids on the Block: Novel ARVs for Multidrug Resistance (9/30/25)

- Case 6. Is More Really More? Optimizing Options for a Healthy Patient (9/16/25)

Clinical Guidelines Program Approach to Shared Decision-Making

Download Printable PDF of Shared Decision-Making Statement

Date of current publication: August 8, 2023

Lead authors: Jessica Rodrigues, MS; Jessica M. Atrio, MD, MSc; and Johanna L. Gribble, MA

Writing group: Steven M. Fine, MD, PhD; Rona M. Vail, MD; Samuel T. Merrick, MD; Asa E. Radix, MD, MPH, PhD; Christopher J. Hoffmann, MD, MPH; Charles J. Gonzalez, MD

Committee: Medical Care Criteria Committee

Date of original publication: August 8, 2023

Rationale

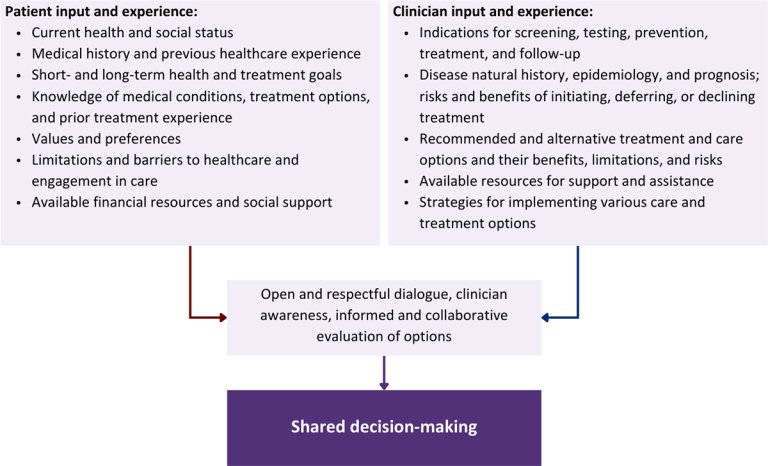

Throughout its guidelines, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) AIDS Institute (AI) Clinical Guidelines Program recommends “shared decision-making,” an individualized process central to patient-centered care. With shared decision-making, clinicians and patients engage in meaningful dialogue to arrive at an informed, collaborative decision about a patient’s health, care, and treatment planning. The approach to shared decision-making described here applies to recommendations included in all program guidelines. The included elements are drawn from a comprehensive review of multiple sources and similar attempts to define shared decision-making, including the Institute of Medicine’s original description [Institute of Medicine 2001]. For more information, a variety of informative resources and suggested readings are included at the end of the discussion.

Benefits

The benefits to patients that have been associated with a shared decision-making approach include:

- Decreased anxiety [Niburski, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Increased trust in clinicians [Acree, et al. 2020; Groot, et al. 2020; Stalnikowicz and Brezis 2020]

- Improved engagement in preventive care [McNulty, et al. 2022; Scalia, et al. 2022; Bertakis and Azari 2011]

- Improved treatment adherence, clinical outcomes, and satisfaction with care [Crawford, et al. 2021; Bertakis and Azari 2011; Robinson, et al. 2008]

- Increased knowledge, confidence, empowerment, and self-efficacy [Chen, et al. 2021; Coronado-Vázquez, et al. 2020; Niburski, et al. 2020]

Approach

Collaborative care: Shared decision-making is an approach to healthcare delivery that respects a patient’s autonomy in responding to a clinician’s recommendations and facilitates dynamic, personalized, and collaborative care. Through this process, a clinician engages a patient in an open and respectful dialogue to elicit the patient’s knowledge, experience, healthcare goals, daily routine, lifestyle, support system, cultural and personal identity, and attitudes toward behavior, treatment, and risk. With this information and the clinician’s clinical expertise, the patient and clinician can collaborate to identify, evaluate, and choose from among available healthcare options [Coulter and Collins 2011]. This process emphasizes the importance of a patient’s values, preferences, needs, social context, and lived experience in evaluating the known benefits, risks, and limitations of a clinician’s recommendations for screening, prevention, treatment, and follow-up. As a result, shared decision-making also respects a patient’s autonomy, agency, and capacity in defining and managing their healthcare goals. Building a clinician-patient relationship rooted in shared decision-making can help clinicians engage in productive discussions with patients whose decisions may not align with optimal health outcomes. Fostering open and honest dialogue to understand a patient’s motivations while suspending judgment to reduce harm and explore alternatives is particularly vital when a patient chooses to engage in practices that may exacerbate or complicate health conditions [Halperin, et al. 2007].

Options: Implicit in the shared decision-making process is the recognition that the “right” healthcare decisions are those made by informed patients and clinicians working toward patient-centered and defined healthcare goals. When multiple options are available, shared decision-making encourages thoughtful discussion of the potential benefits and potential harms of all options, which may include doing nothing or waiting. This approach also acknowledges that efficacy may not be the most important factor in a patient’s preferences and choices [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Clinician awareness: The collaborative process of shared decision-making is enhanced by a clinician’s ability to demonstrate empathic interest in the patient, avoid stigmatizing language, employ cultural humility, recognize systemic barriers to equitable outcomes, and practice strategies of self-awareness and mitigation against implicit personal biases [Parish, et al. 2019].

Caveats: It is important for clinicians to recognize and be sensitive to the inherent power and influence they maintain throughout their interactions with patients. A clinician’s identity and community affiliations may influence their ability to navigate the shared decision-making process and develop a therapeutic alliance with the patient and may affect the treatment plan [KFF 2023; Greenwood, et al. 2020]. Furthermore, institutional policy and regional legislation, such as requirements for parental consent for gender-affirming care for transgender people or insurance coverage for sexual health care, may infringe upon a patient’s ability to access preventive- or treatment-related care [Sewell, et al. 2021].

Figure 1: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Download figure: Elements of Shared Decision-Making

Health equity: Adapting a shared decision-making approach that supports diverse populations is necessary to achieve more equitable and inclusive health outcomes [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016]. For instance, clinicians may need to incorporate cultural- and community-specific considerations into discussions with women, gender-diverse individuals, and young people concerning their sexual behaviors, fertility intentions, and pregnancy or lactation status. Shared decision-making offers an opportunity to build trust among marginalized and disenfranchised communities by validating their symptoms, values, and lived experience. Furthermore, it can allow for improved consistency in patient screening and assessment of prevention options and treatment plans, which can reduce the influence of social constructs and implicit bias [Castaneda-Guarderas, et al. 2016].

Clinician bias has been associated with health disparities and can have profoundly negative effects [FitzGerald and Hurst 2017; Hall, et al. 2015]. It is often challenging for clinicians to recognize and set aside personal biases and to address biases with peers and colleagues. Consciously or unconsciously, negative or stigmatizing assumptions are often made about patient characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, mental health, and substance use [Avery, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013; Livingston, et al. 2012]. With its emphasis on eliciting patient information, a shared decision-making approach encourages clinicians to inquire about patients’ lived experiences rather than making assumptions and to recognize the influence of that experience in healthcare decision-making.

Stigma: Stigma may prevent individuals from seeking or receiving treatment and harm reduction services [Tsai, et al. 2019]. Among people with HIV, stigma and medical mistrust remain significant barriers to healthcare utilization, HIV diagnosis, and medication adherence and can affect disease outcomes [Turan, et al. 2017; Chambers, et al. 2015], and stigma among clinicians against people who use substances has been well-documented [Stone, et al. 2021; Tsai, et al. 2019; van Boekel, et al. 2013]. Sexual and reproductive health, including strategies to prevent HIV transmission, acquisition, and progression, may be subject to stigma, bias, social influence, and violence.

| SHARED DECISION-MAKING IN HIV CARE |

|

Resources and Suggested Reading

In addition to the references cited below, the following resources and suggested reading may be useful to clinicians.

| RESOURCES |

References

Acree ME, McNulty M, Blocker O, et al. Shared decision-making around anal cancer screening among black bisexual and gay men in the USA. Cult Health Sex 2020;22(2):201-16. [PMID: 30931831]

Avery JD, Taylor KE, Kast KA, et al. Attitudes toward individuals with mental illness and substance use disorders among resident physicians. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2019;21(1):18m02382. [PMID: 30620451]

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med 2011;24(3):229-39. [PMID: 21551394]

Castaneda-Guarderas A, Glassberg J, Grudzen CR, et al. Shared decision making with vulnerable populations in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med 2016;23(12):1410-16. [PMID: 27860022]

Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 2015;15:848. [PMID: 26334626]

Chen CH, Kang YN, Chiu PY, et al. Effectiveness of shared decision-making intervention in patients with lumbar degenerative diseases: a randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(10):2498-2504. [PMID: 33741234]

Coronado-Vázquez V, Canet-Fajas C, Delgado-Marroquín MT, et al. Interventions to facilitate shared decision-making using decision aids with patients in primary health care: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020;99(32):e21389. [PMID: 32769870]

Coulter A, Collins A. Making shared decision-making a reality: no decision about me, without me. 2011. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Making-shared-decision-making-a-reality-paper-Angela-Coulter-Alf-Collins-July-2011_0.pdf

Crawford J, Petrie K, Harvey SB. Shared decision-making and the implementation of treatment recommendations for depression. Patient Educ Couns 2021;104(8):2119-21. [PMID: 33563500]

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics 2017;18(1):19. [PMID: 28249596]

Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, et al. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020;117(35):21194-21200. [PMID: 32817561]

Groot G, Waldron T, Barreno L, et al. Trust and world view in shared decision making with indigenous patients: a realist synthesis. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):503-14. [PMID: 31750600]

Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015;105(12):e60-76. [PMID: 26469668]

Halperin B, Melnychuk R, Downie J, et al. When is it permissible to dismiss a family who refuses vaccines? Legal, ethical and public health perspectives. Paediatr Child Health 2007;12(10):843-45. [PMID: 19043497]

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

KFF. Key data on health and health care by race and ethnicity. 2023 Mar 15. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/report/key-data-on-health-and-health-care-by-race-and-ethnicity/ [accessed 2023 May 19]

Livingston JD, Milne T, Fang ML, et al. The effectiveness of interventions for reducing stigma related to substance use disorders: a systematic review. Addiction 2012;107(1):39-50. [PMID: 21815959]

McNulty MC, Acree ME, Kerman J, et al. Shared decision making for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with black transgender women. Cult Health Sex 2022;24(8):1033-46. [PMID: 33983866]

Niburski K, Guadagno E, Abbasgholizadeh-Rahimi S, et al. Shared decision making in surgery: a meta-analysis of existing literature. Patient 2020;13(6):667-81. [PMID: 32880820]

Parish SJ, Hahn SR, Goldstein SW, et al. The International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health process of care for the identification of sexual concerns and problems in women. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94(5):842-56. [PMID: 30954288]

Robinson JH, Callister LC, Berry JA, et al. Patient-centered care and adherence: definitions and applications to improve outcomes. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20(12):600-607. [PMID: 19120591]

Scalia P, Durand MA, Elwyn G. Shared decision-making interventions: an overview and a meta-analysis of their impact on vaccine uptake. J Intern Med 2022;291(4):408-25. [PMID: 34700363]

Sewell WC, Solleveld P, Seidman D, et al. Patient-led decision-making for HIV preexposure prophylaxis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep 2021;18(1):48-56. [PMID: 33417201]

Stalnikowicz R, Brezis M. Meaningful shared decision-making: complex process demanding cognitive and emotional skills. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26(2):431-38. [PMID: 31989727]

Stone EM, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, et al. The role of stigma in U.S. primary care physicians’ treatment of opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 2021;221:108627. [PMID: 33621805]

Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, et al. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med 2019;16(11):e1002969. [PMID: 31770387]

Turan B, Budhwani H, Fazeli PL, et al. How does stigma affect people living with HIV? The mediating roles of internalized and anticipated HIV stigma in the effects of perceived community stigma on health and psychosocial outcomes. AIDS Behav 2017;21(1):283-91. [PMID: 27272742]

van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2013;131(1-2):23-35. [PMID: 23490450]

NYSDOH HIV Care Provider Definitions

Note on “experienced” HIV care providers: The NYSDOH AI Clinical Guidelines Program defines an “experienced HIV care provider” as a practitioner who has been accorded HIV Specialist status by the American Academy of HIV Medicine. Nurse practitioners (NPs) and licensed midwives who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV in collaboration with a physician may be considered experienced HIV care providers if all other practice agreements are met; NPs with more than 3,600 hours of qualifying experience do not require collaboration with a physician (8 NYCRR 79-5:1; 10 NYCRR 85.36; 8 NYCRR 139-6900). Physician assistants who provide clinical care to individuals with HIV under the supervision of an HIV Specialist physician may also be considered experienced HIV care providers (10 NYCRR 94.2).

June 2016 Policy Statement: Defining Program Eligibility by HIV Status

State’s AIDS Institute Issues Clinical Guidance Recommending All HIV-Related Care be Initiated Immediately Upon Diagnosis – OTDA Significantly Expanding Eligibility For Emergency Shelter Allowance

Expanding Preventative Care is a Vital Component of Governor Cuomo’s Unprecedented Commitment to End the AIDS Epidemic in New York

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo today announced all HIV-positive individuals in New York City will become eligible to receive housing, transportation and nutritional support. The significant expansion of eligibility for Emergency Shelter Assistance is a result of a policy issued by the State Department of Health’s AIDS Institute that eliminates the technical distinction between those who are considered in need of care and those who are not. It has long been proven that all individuals who are diagnosed with HIV – whether they show symptoms or do not – benefit from receiving care.

“With today’s compassionate and common sense guidance, we are creating a better future for all New Yorkers living with an HIV positive diagnosis,” Governor Cuomo said. “Our commitment to fighting this disease is unrelenting and guided by our remembrance of those we lost. Every individual living with HIV should have access to life-saving care, regardless of whether or not they are symptomatic of the disease at that moment.” Read more

Meningococcal Disease: NYSDOH Health Advisory and Vaccine Recommendations

NYSDOH Meningococcal Vaccine Recommendations for HIV-Infected Individuals and Those at High Risk of HIV Infection

October 25, 2016 | View the 10/25/16 NYS Health Advisory

On June 22, 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted to recommend that persons aged ≥2 months with HIV infection should receive meningococcal conjugate (MenACWY) vaccine, either MenACWY-D (Menactra®), MenACWY-CRM (Menveo®) or, as age-appropriate, Hib-MenCY-TT (MenHibrix®, recommended for ages 2-18 months).

This recommendation was made based on epidemiologic data demonstrating an increased risk of invasive meningococcal disease (IMD) due to serogroups C, W, and Y among HIV-infected persons in the United States. HIV-infected individuals have suppressed immune responses to MenACWY vaccine, as well as waning of vaccine-induced immunity. For this reason, a multidose primary series and regular booster doses are necessary to maintain protection against IMD. HIV-infected persons have not been demonstrated to be at increased risk of serogroup B disease, and use of serogroup B (MenB) vaccine has not been studied in this group; for this reason MenB vaccine is not recommended for HIV-infected persons unless they have another indication for this vaccine.

In response to the ACIP recommendations, the NYSDOH advises healthcare providers to administer MenACWY vaccine to:

- All HIV-infected children and adults aged 2 months or older, and

- HIV-negative individuals at ongoing high risk for HIV infection, to include:

- Men who have sex with men (MSM) who are candidates for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) as described in the NYSDOH AIDS Institute “Guidance for the Use of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis to Prevent HIV Transmission” and

- Transgender individuals who are candidates for PrEP.

Read the full NYS Health Advisory, which includes additional information regarding dosing and vaccine cost reimbursement.

Previous IMD-Related Health Advisories and Alerts

- June 30, 2015: NYS Informational Message: Informational Message: Invasive Meningococcal Disease in Men Who Have Sex With Men

- June 12, 2015: NYC 2015 Health Alert #11: UPDATE: Invasive Meningococcal Disease in Men Who Have Sex with Men

- September 5, 2014: NYC 2014 Health Alert #28: Update on Invasive Meningococcal Disease in Men Who Have Sex With Men

- July 18, 2014: NYC 2014 Health Alert #15: Update on Invasive Meningococcal Disease in Men Who Have Sex With Men

- August 14, 2013: NYC 2013 Health Alert #31: Update on Invasive Meningococcal Disease in Men Who Have Sex With Men

- March 21, 2013: NYS 2013 Health Advisory Update #1: Expanded Outbreak Response Meningococcal Vaccine Recommendations for Men Who Have Sex With Men

- March 6, 2013: NYC 2013 Health Alert #5: UPDATE: Invasive Meningococcal Disease in Men Who Have Sex With Men, Expanded Vaccine Recommendations

- November 29, 2012: NYC 2012 Health Alert #36: UPDATE: Invasive Meningococcal Disease in Men Who Have Sex With Men

- October 22, 2012: NYC 2012 Health Alert #30: UPDATE: Invasive Meningococcal Disease in Men Who Have Sex With Men

- October 4, 2012: NYS 2012 Health Advisory/NYC 2012 Health Alert #28: UPDATE: Meningococcal Vaccine Recommendations for HIV-Infected Men Who Have Sex With Men

- September 27, 2012: NYC 2012 Health Alert #27: Invasive Meningococcal Disease in Men Who Have Sex With Men

More Information

- Health Department Clinic Locations

- If you think you might be at risk, please read the patient fact sheet

- March 22, 2013: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention and Control of Meningococcal Disease: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2013;62(RR-2):1-22.

- January 4, 2013: Notes from the Field: Serogroup C Invasive Meningococcal Disease Among Men Who Have Sex With Men — New York City, 2010–2012, Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2013;61(51);1048.

Mental Health Screening Tools

August 2021

| Mental Health Screening Tools | ||

| Screening Tool | Administration | Notes |

| BAI (Beck Anxiety Inventory) |

|

— |

| BDI-II (Beck Depression Inventory-II) [a] |

|

|

| BSI 18 (Brief Symptom Inventory 18) |

|

|

| CDQ (Client Diagnostic Questionnaire) |

|

|

| CESD-R (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale Revised) [a] |

|

|

| DRS-2 (Dementia Rating Scale-2) |

|

|

| HAM-D/HDI (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale) |

|

|

| HANDS (Harvard Dept. of Psychiatry, NDSD Scale) |

|

|

| IHDS (International HIV Dementia Scale) |

|

|

| Mental Alternation Test |

|

|

| MHDS (Modified HIV Dementia Scale) |

|

|

| MMSE (Mini-Mental State Exam) |

|

|

| Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) – Mental Disorders Screening – National HIV Curriculum (uw.edu) |

|

|

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) – Mental Disorders Screening – National HIV Curriculum (uw.edu) [a] |

|

|

| PHQ-15 (Patient Health Questionnaire-15) |

|

|

| PRIME-MD (Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders) |

|

|

| SAMISS (Substance Abuse and Mental Illness Symptoms Screener) [b] |

|

|

| ZUNG (Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale) |

|

|

| Notes: a. Any of these instruments (CESD-R, HADS, PHQ-9, BDI-II) may be acceptable to screen for depression in the medically ill, although the evidence for the utility of the HADS is less strong than for the CES and BDI-II. The PHQ has better sensitivity and specificity than the HADS. The cutoff score used on any of these instruments should depend on the purpose of screening and resources for follow up [Levenson 2005]. b. For other alcohol- and substance use-related screening tools, see NYSDOH AI guideline Substance Use Screening, Risk Assessment, and Use Disorder Diagnosis in Adults. |

||

References

Bing EG, Burnam MA, Longshore D, et al. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001;58(8):721-728. [PMID: 11483137]

Levenson JL. 2005. Textbook of Psychosomatic Medicine. American Psychiatric Publishing.

Whetten K, Reif S, Swartz M, et al. A brief mental health and substance abuse screener for persons with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2005;19(2):89-99. [PMID: 15716640]

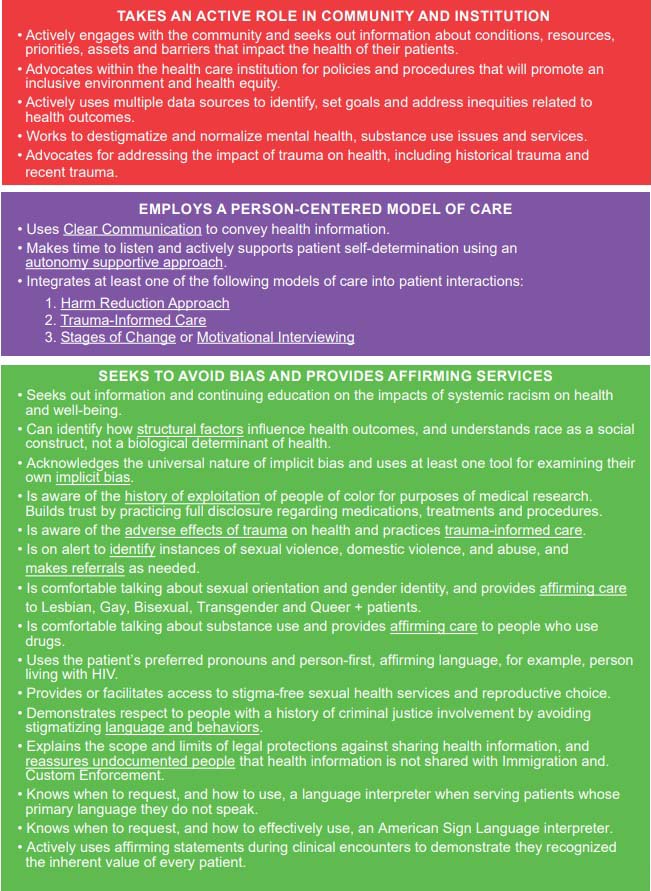

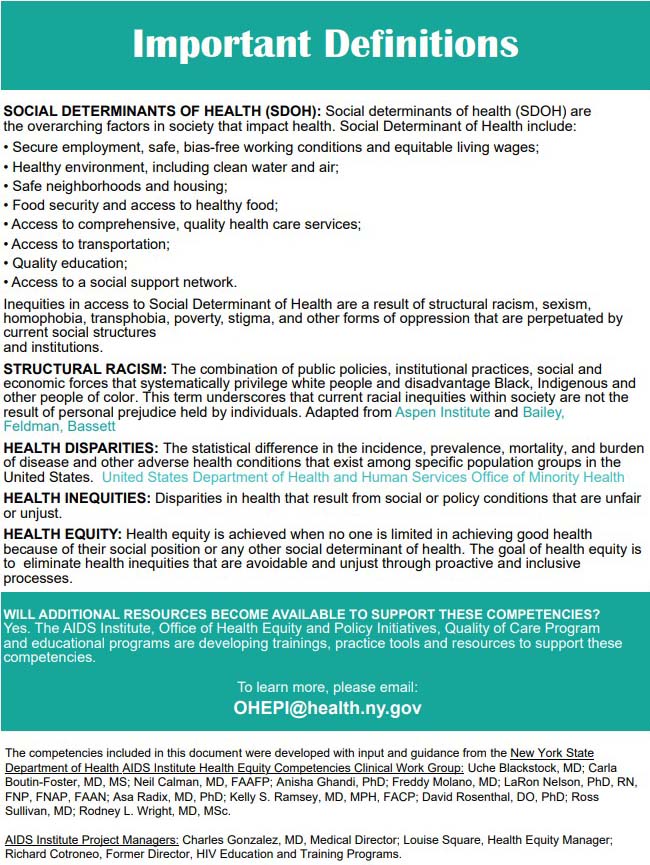

NYSDOH Health Equity Competencies for Health Care Providers

October 2024

Download Printable PDF of Health Equity Competencies

Health Equity Competencies Page 1

Health Equity Competencies Page 2

Health Equity Competencies Page 3

Selected Links: Resources for Clinicians

June 2023

New York State Department of Health:

- CEI: HIV Primary Care and Prevention, Sexual Health, HCV Treatment, and Drug User Health

- CEI for Clinical Training in HIV, STIs, HCV, and Drug User Health

- CEI Project ECHO

- NYS AIDS Institute Training Centers

- Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

- Wadsworth Center

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases

- Provider Reporting & Partner Services

- Partner Services: What Health Care Providers Need to Know

- HIV/AIDS Laws & Regulations

- Office of Addiction Services and Support

- Office of Mental Health

- Beyond Status

- Ending the Epidemic

New York City Health:

- Contact Notification Assistance Program (CNAP)

- STD and HIV Services, including Clinic Locations and Hours

AIDS Education Training Center (AETC):

Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry: For Health Care Providers

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

ClinicalInfo.HIV.gov:

University of California San Francisco (UCSF):

- Clinician Consultation Center: HIV/AIDS Management

- Center for Excellence in Transgender Health

- Guidelines for the Primary and Gender-Affirming Care of Transgender and Gender Nonbinary People

University of Liverpool: HIV Drug Interactions

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: HIV/AIDS Image Library

Selected Links: Resources for Consumers

June 2023

New York State Department of Health:

- HIV/AIDS Basics

- Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Partner Services

- Uninsured Care Programs

- YGetIt? Project

- AIDS Institute Provider Directory (HIV, HCV, PEP, PrEP, Buprenorphine, STI Services, Opioid Overdose Prevention Program)

- Beyond Status

- Ending the Epidemic

- Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

- Drug User Health

New York City Health:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): HIV Basics

HIVinfo.NIH.gov: Understanding HIV

NAM Aidsmap: HIV Basics

The Body: The HIV/AIDS Resource

All FDA-Approved HIV Medications, With Brand Names and Abbreviations

Reviewed January 2026

Listed below are all FDA-approved HIV medications as of July 3, 2025, per HIVinfo.NIH.gov, with links to the Clinical Info HIV.gov drug database. The list is organized by drug class, with individual drugs listed in alphabetical order. Combination drugs are also listed in alphabetical order.

Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTIs): characteristics

- Abacavir (ABC; Ziagen): FDA label | Patient info

- Emtricitabine (FTC; Emtriva): FDA label | Patient info

- Lamivudine (3TC; Epivir): FDA label | Patient info

- Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF; Viread): FDA label | Patient info

- Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF; Vemlidy): FDA label | Patient info

- Zidovudine (AZT, ZDV; Retrovir): FDA label | Patient info

Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTIs): characteristics

- Doravirine (DOR; Pifeltro): FDA label | Patient info

- Efavirenz (EFV; Sustiva*): FDA label | Patient info

- Etravirine (ETR; Intelence): FDA label | Patient info

- Nevirapine (NVP; Viramune*, Viramune XR [extended release]*): FDA label | Patient info

- Rilpivirine (RPV; Edurant, Edurant PED*): FDA label | Patient info

Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors (INSTIs): characteristics

- Cabotegravir (CAB; Apretude [injection]; Vocabria [tablet]): FDA label | Patient info

- Dolutegravir (DTG; Tivicay, Tivicay PD): FDA label | Patient info

- Raltegravir (RAL; Isentress, Isentress HD): FDA label | Patient info

Protease Inhibitors (PIs): characteristics

- Atazanavir (ATV; Reyataz): FDA label | Patient info

- Darunavir (DRV; Prezista): FDA label | Patient info

- Fosamprenavir (FPV; Lexiva*): FDA label | Patient info

- Ritonavir (RTV; Norvir): FDA label | Patient info

- Tipranavir (TPV; Aptivus): FDA label | Patient info

Fusion Inhibitor: characteristics

- Enfuvirtide (T-20; Fuzeon*): FDA label | Patient info

CCR5 Antagonist: characteristics

- Maraviroc (MVC; Selzentry): FDA label | Patient info

Attachment Inhibitor: characteristics

- Fostemsavir (FTR; Rukobia): FDA label | Patient info

Post-Attachment Inhibitor: characteristics

- Ibalizumab-uiyk (IBA; Trogarzo): FDA label | Patient info

Capsid Inhibitor: characteristics

- Lenacapavir (LEN; Sunlenca [for treatment], Yeztugo [for prevention]): FDA label | Patient info

Pharmacokinetic Enhancer: characteristics

- Cobicistat (COBI; Tybost): FDA label | Patient info

Combination HIV Medications:

- Abacavir/lamivudine (ABC/3TC; Epzicom*): FDA label | Patient info

- Abacavir/dolutegravir/lamivudine (ABC/DTG/3TC; Triumeq, Triumeq PD): FDA label | Patient info

- Abacavir/lamivudine/zidovudine (ABC/3TC/ZDV; Trizivir*): FDA label | Patient info

- Atazanavir/cobicistat (ATV/COBI; Evotaz): FDA label | Patient info

- Bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (BIC/FTC/TAF; Biktarvy): FDA label | Patient info

- Cabotegravir/rilpivirine (CAB/RPV; Cabenuva): FDA label | Patient info

- Darunavir/cobicistat (DRV/COBI; Prezcobix): FDA label | Patient info

- Darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alefenamide (DRV/COBI/FTC/TAF; Symtuza): FDA label | Patient info

- Dolutegravir/lamivudine (DTG/3TC; Dovato): FDA label | Patient info

- Dolutegravir/rilpivirine (DTG/RPV; Juluca): FDA label | Patient info

- Doravirine/lamivudine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (DOR/3TC/TDF; Delstrigo): FDA label | Patient info

- Efavirenz/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (EFV/FTC/TDF; Atripla*): FDA label | Patient info

- Efavirenz/lamivudine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (EFV/3TC/TDF; Symfi, Symfi Lo*): FDA label | Patient info

- Elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (EVG/COBI/FTC/TAF; Genvoya): FDA label | Patient info

- Elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (EVG/COBI/FTC/TDF; Stribild): FDA label | Patient info

- Emtricitabine/rilpivirine/tenofovir alafenamide (FTC/RPV/TAF; Odefsy): FDA label | Patient info

- Emtricitabine/rilpivirine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/RPV/TDF; Complera): FDA label | Patient info

- Emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (FTC/TAF; Descovy): FDA label | Patient info

- Emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/TDF; Truvada): FDA label | Patient info

- Lamivudine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (3TC/TDF; Cimduo): FDA label | Patient info

- Lamivudine/zidovudine (3TC/ZDV; Combivir*): FDA label | Patient info

- Lopinavir/ritonavir (LPV/r; Kaletra): FDA label | Patient info

*Discontinued

Last updated on July 7, 2025